There were no consultants or researchers to answer her at that morning’s Edcamp, a trending, teacher-driven model of PD. But the 15 teachers who had gathered from around Anne Arundel County, along the Chesapeake Bay, were not shy about sharing their ideas.

Schools need to create a “culture of courage,” one said, where students and teachers feel that they can make mistakes and learn from them. “If it’s OK to not know the answer, students and teachers will ask deeper questions,” added Kate Hoens, the chair of the mathematics department at Glen Burnie High School.

“We have to give students opportunities to discover their strengths,” agreed Tiffany Callaghan, an English teacher at Old Mill Middle School North.

For 40 minutes ideas flowed among the practitioners; nearly everyone had something to add — experiences, observations, theories. Lara said, “I not only got what I needed. I got more.”

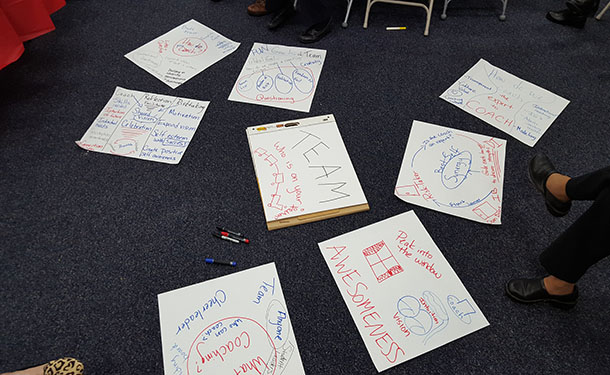

Edcamps were designed to give teachers professional learning they actually want and can use. The subjects and approach of a meeting are shaped by those taking part: Lara initiated the session on coaching at the Anne Arundel Edcamp because it was one of 15 topics, boiled down from dozens, suggested by the 100 educators who attended.

The gatherings are low-budget affairs that would give anyone who has ever organized professional conferences nightmares. Attendance is free, so no one knows how many educators (or students or parents) will show up. There is no pre-set agenda, just a big sheet of paper to which anyone can attach a sticky note with an idea for consideration. Formal presentations and PowerPoints are discouraged. If attendees aren’t getting what they hoped from one session, they are free to find another. And unlike at conferences, sponsors are not allowed to peddle their wares.

A group of Philadelphia teachers originated Edcamps, borrowing the concept from popular techie get-togethers called BarCamps. Their hope was to give educators more control over their professional growth.

The first Edcamp was held at Drexel University in Philadelphia in 2010. The organizers invited their Twitter followers, posted on Facebook, and then hoped for the best. “It was an absolutely spectacular May morning and we thought that no one would show,” said Hadley Ferguson, a longtime history teacher who was one of the organizers.

In fact, 75 teachers turned out. With help from live-tweeting and social media outreach by the attendees, a movement was born.

Eight Edcamps were organized that first year; more than 1,000 have been held across the U.S. and internationally since. Attendance has ranged from 25 to 600, but averages between 75 and 100. The quality has little to do with size, though, and almost everything to do with the commitment of those who show up to discuss what they know and learn what they don’t.

Ferguson said the growing popularity of Edcamps show that it meets a nearly universal need in the profession. “When you tell teachers that this gives you time and space to create and grow together, it is very rare that they don’t move into that space.”

The Edcamp Foundation, which supports independent organizers of the events, was awarded a $2 million grant last year from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to disseminate the model. Edcamp hired Ferguson as executive director and will use the grant to put on hundreds of Edcamps, at a typical cost of $300 each.

Grant money also will be used to increase the impact of Edcamps on classrooms. The foundation has begun providing up to $1,000 to teachers who want to implement an idea they took home from Edcamp in their school.

The grants have been used for small but meaningful projects and improvements: creating an Edcamp-style experience for middle schoolers learning about the sinking of the Titanic, covering substitute costs so a teacher could observe how a colleague uses a popular app with students, and setting up a Wi-Fi hotspot for students who do not have access to the Internet at home.

Ferguson said the open-ended format “treats teachers as professionals who care desperately about improving their practice, rather than as people who need to be fixed on a professional development day.”

Professional development isn’t traditionally a grassroots movement, but by its nature Edcamp grows only if educators want it — and it has grown rapidly.

Considering the results of a 2014 Gates Foundation survey, this might have been expected. The survey found that most teachers want to improve their practice to help students but many find professional development opportunities to be “not relevant, not effective, and most important of all, not connected to their core work of helping students learn.”

Only 29 percent of teachers were “highly satisfied” with the learning opportunities available to them.

By contrast, Edcamp has caught on in part because teachers who attend convey their enthusiasm in social media. Participants at the Anne Arundel Edcamp sent out more than 200 tweets, calling it “a great experience” that was “full of new ideas and passionate colleagues.”

Those new ideas reflected the amazing variety of interests among teachers who attended, ranging from how best to integrate different disciplines in an International Baccalaureate program to project-based learn to using movement in the classroom to boost attention and cognition. No standard PD program has the flexibility and expertise to respond to teachers interests in this way — only the teachers themselves can do it.

Anne Arundel Deputy Superintendent Maureen McMahon is a big believer in Edcamps. “We really want teachers to feel empowered to build the learning communities of tomorrow,” she said. “This adds the spark back into education, and lets teachers know that they can lead with their ideas from the classroom.”

This is equally true at Edcamps that are more narrowly focused, as with a March gathering in Morristown, New Jersey that dealt mostly with assistive technologies for students with disabilities.

Margaux Urciuoli, who teaches children with multiple disabilities at a private school, said technology makes it possible for her students to learn. “So I have to stay current with what’s out there,” she said.

Sparta High School social studies teacher Christina Lami said professional learning usually means sitting in an auditorium listening to “higher ups” talk, but she would rather learn from “teachers in the trenches with you, because they understand what you’re going through.”

The Edcamp Foundation is readying a formal evaluation of the model to better measure its effectiveness, but anecdotal evidence suggests that it’s successful in at least one way. Teachers believe that it helps them become more effective.

Jennifer Lara said her coaching session reinforced the fact that teachers highly value “having a voice in their own professional development matters”

She added, “they don’t just want more one-and-done workshops on random topics.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)