Duran: Young People Facing Challenges Need Schools & Services to Work Together to Support and Nurture Them as They Build Their Futures

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

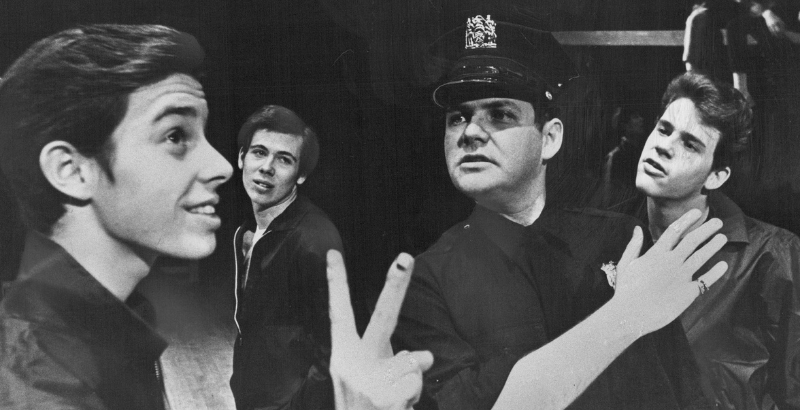

When I first saw West Side Story, one moment brought me back to my high school principal’s office. The Jets were singing, “We ain’t no delinquents, we’re misunderstood. Deep down inside us there is good!”

I could have said the same thing when my principal was suspending me for truancy. He told me I would never amount to anything.

But he never understood why I missed school. I had to be at home to care for my younger brothers when my mother was hospitalized for her lifelong mental illness and my father was working at his job in construction.

And in the same way the Jets sang about Officer Krupke behind his back, I could never tell my principal that to his face.

While a lot has changed since Stephen Sondheim wrote those lyrics almost 60 years ago, too often police, school officials and even professionals dedicated to serving young people don’t understand that most teenagers are trying to be their best selves even under the most trying circumstances.

What they lack are safe and supportive environments to learn, play, work and grow.

The need is greater than ever. As many as 3 million children have had minimal or no sustained access to school since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and many of them may never return. Almost 200,000 children have lost a parent to the pandemic. At any given moment, 1 in 30 American children is homeless. Almost half a million children are in foster care, and few of them will ever live in a stable home.

To find out how to address those needs, the Forum for Youth Investment and our partners asked young adults who had been in the child welfare system how to improve the experiences of children today.

We heard what researchers have been saying for decades: Young people’s learning and development are shaped by the interactions they have with adults across all settings in their life. That is why our organization forges common agendas to bring about systemic change at the federal, state and local levels. No one public agency, organization or sector can provide young people with everything they need to succeed. But an approach that partners across systems — education, workforce development, government, nonprofit, philanthropic, business, health and human services, and youth justice — can improve outcomes for young people.

Our country must transform youth services so teenagers are valued for their strengths, not criticized for their deficits; empowered to achieve their fullest potential, not connected to their parents’ poverty or other challenges; judged by their character, not dismissed by the style of their clothes, the color of their skin, or the way they talk.

Natasha Jones, now a graduate student who had been in foster homes as a child, told us: “You might look like a system, but what I need is a relationship.” The child welfare system can intervene in a crisis, she said, but it didn’t address her most basic need: connecting to the community, where she could find mentors at schools, faith-based organizations and employers.

Jodi Harper, a native Hawaiian who lived in foster homes starting at birth, found such a connection at school, where she succeeded on her own and learned that her “experiences in child welfare weren’t my fault.”

Our takeaway was that young people need an ecosystem. In other words, the systems created and funded to support them have to align and coordinate to shape learning and development, to enable adults to form positive relationships with youth and provide the dignity, tools and training they deserve.

This work will be difficult. But we have already seen collaborations over the course of the pandemic integrate education, health care and social services across government and nonprofits.

At the height of COVID-19, schools and community-based partners relied on each other more than ever before to meet the most pressing needs of students and their families. Community-based organizations provided safe environments for children of essential workers to log in to virtual classes. Schools worked with community and health and human services agencies to create mobile hotspots for internet connectivity, and provided services including nutritious meals, masks and other health care supplies to families who could not afford or access these vital resources.

Now, they are working together to reimagine summer learning and engage adolescents in developing skills for work now and in the future. And maybe, most importantly, show young people how to advocate for themselves and help adults understand how to meet their needs.

Expanding this work even further will require an investment of time, energy and funding. As with any investment, it will pay dividends in the future, as these changes prepare struggling youth to thrive as community leaders and contribute to the economy. Without these changes, the lifelong costs will put additional strain on corrections, unemployment and other public services.

In this new ecosystem, Officer Krupke deserves a make-over. Instead of a beat cop, he’s a well-trained community police officer who listens to young people, partners with the community and understands their needs. He has relationships to coordinate with the teachers, afterschool professionals, counselors, mentors and others who can support young people in all aspects of their life.

I am living proof that these kinds of relationships matter. My high school principal didn’t believe in me, but many others in my hometown’s school community did. They treated my family with dignity and respect, provided me with the supports, relationships and opportunities to stay connected to school and launched me to a career where I can now help build the system that will do the same for millions of young people today.

Mishaela Durán is president and CEO of the Forum for Youth Investment, a national nonprofit “action tank” that helps state and local leaders leverage research, policy and practice so all children and youth are ready for college, work and life.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)