Hawaii Officials: Number of Students Missing, Killed In Maui Fires Is ‘Too Small’ To Release

Parents demanded more transparency from education officials at a meeting Thursday.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The Hawaii Department of Education says the number of students listed as missing or killed in the Lahaina fire is so small that releasing it would violate their privacy.

This comes as the department announced it has been unable to make contact with nearly 500 families in its system more than a month after the disaster that killed at least 115 people and displaced thousands.

Education officials have faced a groundswell of anger following the Aug. 8 fire that razed entire blocks. At a meeting on Maui last month, many families from Lahaina expressed concerns over plans to relocate students and the timing for reopening school campuses.

At a Board of Education meeting Thursday in Honolulu, parents lined up to call for more transparency about efforts to find children who have not yet re-enrolled in school.

Superintendent Keith Hayashi said the department knows the whereabouts and education plans of most of the some 3,000 students who had been enrolled in Lahaina before the fire.

He said 907 of them have enrolled in the state’s distance learning program and 782 have enrolled in other public schools. Nearly 345 students are now enrolled in charter schools, private schools or have withdrawn, he said.

“We are actively reaching out to contact families for the remainder of students who have not yet enrolled in an option, knowing that some may have moved out of state or have paused their child’s education for the time being,” he said.

Trying To Reach Families

After the meeting, DOE spokeswoman Nanea Kalani said the department has not heard back from 463 families that it has tried to call. There are 32 families that still have not been called as the department works its way down its list of phone numbers, she said.

She also explained why the department has not released a number of those believed to have died or who remain missing. “For students, we can’t release their identities or numbers right now because the n-size is so small. The n-size is too small, if we said it we’d be in effect identifying them,” she said. N-size is a term used to describe a small subset of students.

Kalani pointed out that Maui County has a list with the names of people who are unaccounted for.

“The Maui Police Department is the lead on making those identifications,” she said, “and then their privacy rests with their parents to disclose whether they were students.”

Many attendees at the meeting called on the DOE to release more information and expressed concern about the well-being of children and families that have not been contacted.

“There’s a lot of anxiety because the students aren’t being identified as safe or deceased,” said Susan Pcola-Davis. “What I don’t understand is why. Why haven’t all the calls been made?”

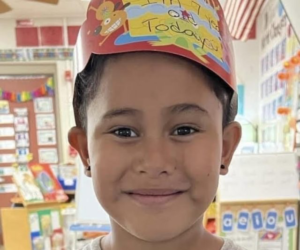

One child, 7-year-old Tony Takafua, has so far been included on the official list of the deceased released by the Maui Police Department. On Thursday, the death toll remained at 115 with 60 individuals identified. Five of those individuals’ families have not yet been notified.

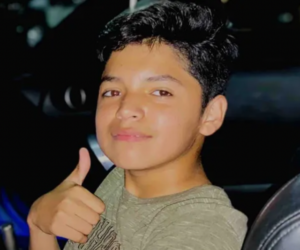

Fourteen-year-old Keyiro Fuentes was identified as a victim by his family, though he has not been officially identified by police. Loved ones have said he was an incoming junior at Lahainaluna High School.

When asked by members of the board why the process of contacting all the families has taken so long, Deputy Superintendent Heidi Armstrong described a “chaotic” situation in the immediate aftermath of the fires.

Cellphone service and internet connections were down in Lahaina and surrounding areas. But she said Department of Education staff started “taking action from the first week.”

Reopening Plans

Staff members and school principals went to Red Cross shelters to try to identify families and students, she said. When shelters began closing and displaced people moved into hotels, school officials continued their searches there.

Department employees are trying to call every family that hasn’t been contacted in person, but sometimes calls aren’t answered or returned, and in some cases voicemail boxes are full or nonexistent, making it impossible to leave a message, she said.

King Kamehameha III Elementary School was destroyed and the three other public schools in town, Princess Nahi‘ena‘ena, Lahaina Intermediate and Lahainaluna High, are closed.

Lahainaluna High students will go to school temporarily at Kulanihakoʻi High in Kihei beginning Sept. 14, according to the department. Students have access to free school bus transportation from West Maui.

Hayashi said he hopes to reopen the three Lahaina schools that weren’t destroyed “as soon as safely possible” and is aiming for sometime after fall break, which takes place Oct. 9-13.

The department is working with contractors to conduct soil sampling around the school and evaluate the water quality, and the Department of Health has installed air quality sensors at the three campuses, he said. Professional services will also clean the schools and school officials will revise evacuation plans before schools reopen, he said.

Hayashi said the department had facilitated a 24/7 mental health hotline through the Hawaii Medical Service Association and made therapists available in schools and at community centers in Lahaina and Wailuku.

Sites around West Maui, including churches and hotels, are being considered to serve as temporary classroom sites, and the state has plans to open in-person distance learning hubs for certain students, including those with special education needs and those in the Hawaiian language immersion program. Those hubs would also provide meals and mental health services, he said.

Enoka-Shayne Bingo told department officials during the meeting that community members want to be more involved in the recovery process.

“Let the village of all of these islands help,” he said. “Let us through this red tape, because we are all suffering with Lahaina.”

This article first appeared on Civil Beat.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)