DIY Downsizing: As Enrollment Drops in NOLA’s All-Charter District, Leaders May Lack Authority to Address the Crisis. Will Schools Agree to Do It Themselves?

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

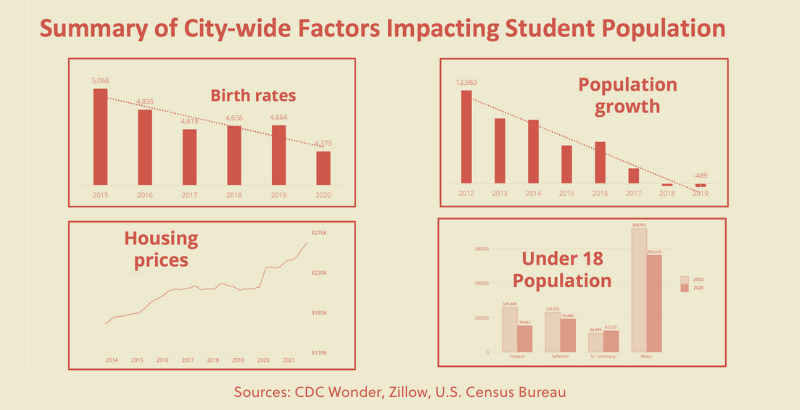

There are some 3,400 unfilled seats in New Orleans Public Schools, and birth rates are falling. The size of incoming kindergarten classes has fallen 17 percent since 2013, while growth in the city’s population flattened between 2015 and 2020.

This news signals an impending crisis, Superintendent Henderson Lewis told Orleans Parish School Board members at a recent meeting, potentially leaving district and school leaders scrambling to cope with a corresponding decrease in state and federal funding.

In most districts, leaders could set new policies to address the looming crisis. But in New Orleans, the nation’s first all-charter district, it’s not at all clear the superintendent and school board have that authority.

If you ask her, says Caroline Roemer, head of the Louisiana Association of Public Charter Schools, “My answer is going to be no.”

In the past, the association has joined lawsuits to counter what it views as impingements on the authority of its members. It intervened in court to counter legal attacks on charter school funding and has fought at the statehouse to preserve the laws granting New Orleans schools autonomy.

NOLA Public Schools leaders say they are not threatening to close down any particular school, but hoping to start a conversation about the impending problem. The best mechanism for “right-sizing” the 48,000-student district, they say, may be for school leaders to come together to voluntarily consider reorganizing.

“The contraction option will not be part of the [charter] renewal process, nor will it be used as a rationale for non-renewal,” a district spokesperson said in a statement to The 74. “Rather, NOLA-PS will work with charter management organizations to determine whether this is a viable option, but it will not be mandated.”

Roemer says the district is responsible for using data from its centralized enrollment system to help schools project how many families will want seats in any given academic year. Schools, in turn, figure out how to accommodate that demand but can act only on the data they’re given.

“You’re now saying there’s a problem and there are too many seats,” she says. “Our schools — their plates are full. The last thing they need right now is to not have accurate projections of enrollment.”

Lewis, who is retiring at the end of the year, may recommend the city’s approximately 80 independent charter schools band together to do the unheard of and downsize voluntarily. By law, schools overseen by the district must maintain a certain level of academic and financial performance or face losing permission to operate.

As he laid out the case for consolidation — which he called “district optimization” — Lewis warned that losing enrollment can set off a vicious cycle in which a school doesn’t have enough students to pay for a full menu of academic and extracurricular offerings, in turn affecting its ability to attract new families.

In a typical district, leaders can shift resources from one school to another to compensate in the short term. In New Orleans, however, budgets are decided by individual schools — part of a series of freedoms granted by state law.

“This work is about the students and viability of our school system,” the New Orleans news site The Lens quoted Lewis as saying. “Knowing our revenues are going down, we need to make sure our kids are taken care of.”

Particularly in urban centers, many school districts have faced declining enrollment for years, caused by a combination of falling birth rates and competition from suburban districts and charter schools. COVID-19 dramatically accelerated the shift. Nationwide, public schools now serve an estimated 1.5 million to 3 million fewer students than they did pre-pandemic, in many places forcing long-overdue conversations.

In Minnesota’s Twin Cities, for example, despite fierce political pressure, St. Paul Public Schools recently announced it would close and consolidate a number of schools in response to two decades of falling enrollment. Minneapolis, by contrast, will spend some $108 million — nearly half its federal pandemic relief funds — to maintain school staffing despite longstanding budget deficits caused by pre-COVID enrollment declines.

New Orleans is different. Its population is smaller than it was before Hurricane Katrina displaced some 250,000 residents in 2005, but its rebound still meant years of enrollment growth for schools. Orleans Parish — Louisiana’s parishes are the equivalent of counties — gained 42,000 residents from 2010 to 2015 alone, boosting public school enrollment by nearly 8,000.

From 2015 to 2020, however, there were fewer than 1,000 new arrivals, and kindergarten classes — whose size predicts enrollment in subsequent grades — started shrinking. Housing prices have skyrocketed, while the number of city residents under 18 has plummeted.

In 2011, the city’s public schools enrolled some 40,000 students. Today, they have nearly 48,000. Private school attendance, meanwhile, fell by 2,000 students, bringing the share of New Orleans children enrolled in what are now district schools to 76 percent.

As enrollment flattens or drops, at least for a while, a traditional district can move resources from one school to another to compensate. But New Orleans schools are funded based on the number of students attending and the needs those children arrive with. When revenue drops, each school has to look internally for ways to balance the budget.

For a single school, enrolling too few students effectively drives up the cost of serving those who remain, according to a preliminary analysis prepared for the district by the advocacy organization New Schools for New Orleans. An example: A school that enrolls 600 students instead of the 675 it aims for has $710,000 less to spend.

At the same time, NOLA Public Schools projects school buildings will need $250 million in capital improvement over the next 10 years, suggesting students should be consolidated in the highest-quality facilities.

The district this year decided not to renew the charters of two schools that have failed to make academic progress for several years in a row. The excess seats mentioned in the recent board presentation do not include those schools’ capacity or a 5 percent buffer the district uses to ensure there are enough seats for new students.

Disclosure: The City Fund provides financial support to New Schools for New Orleans and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)