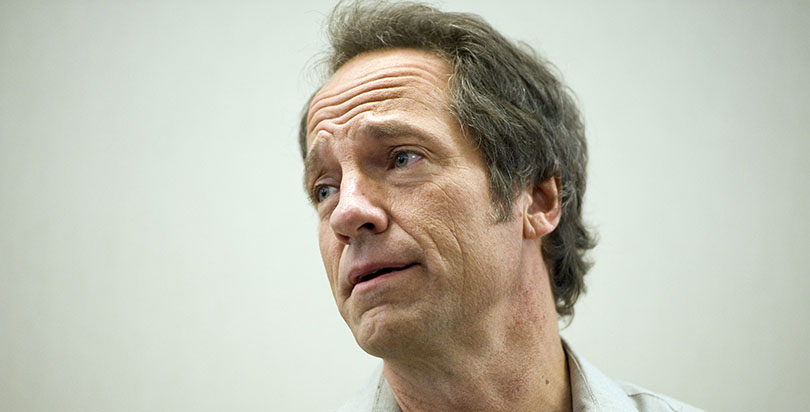

‘Dirty Jobs’ Star Mike Rowe Stumps for Career and Tech Ed as House Readies for New CTE Bill

Washington, D.C.

Maybe the third time will be the charm for Dirty Jobs TV host Mike Rowe.

The career education advocate and TV personality Tuesday made his third appearance at a congressional hearing since 2011, joining a House Education and Workforce subcommittee to discuss strengthening career and technical education as Congress prepares to consider a new bill on the issue.

Rowe’s message, as it was in past appearances before the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee in 2011 and the House Natural Resources Committee in 2014, was simple: Career and technical education, and skilled trade professions, need a PR makeover.

“If you want to make America great again, you’ve got to make work cool again,” he said.

Before he broke through as the host of Dirty Jobs, which highlighted hazardous, arduous, and often disgusting jobs, Rowe was an opera singer as well as a TV host and narrator and salesman for the QVC home shopping network. He has since focused national activism around trades, and he launched the mikeroweWORKS Foundation, which provides scholarships to study skilled trades.

The House late last year passed bipartisan legislation reauthorizing the Carl D. Perkins Act, the primary federal initiative in career and technical training, giving about $1.1 billion annually to colleges and secondary schools. The bipartisan bill would have required states to better align career training programs with workforce needs, while cutting down on required paperwork and limiting federal impositions in the area.

It passed the House 405–5 but was not considered in the Senate. It was reportedly scuttled there over feuds with the Obama education department over implementing the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Rep. Glenn Thompson, a Republican from Pennsylvania who was one of the sponsors of last year’s bill, said Tuesday that he would be reintroducing the legislation shortly.

Subcommittee chairman and Indiana Republican Todd Rokita said he is “very optimistic” about the chances of getting the bill signed into law but cognizant of the hard work ahead in persuading more students to consider career and technical education.

Rowe wasn’t the biggest name testifying at the Capitol Tuesday — Michael Phelps, the winningest Olympian ever, appeared before the Energy and Commerce Committee to discuss anti-doping measures in sports.

The increasing push to get nearly all students to graduate from a four-year college, even if doing so isn’t the best path for their needs and abilities, has come with “unintended consequences,” Rowe said.

Parents and guidance counselors dissuade students from taking career and technical education classes, which are being dropped from many high schools. A career in a trade is seen as “some kind of vocational consolation prize,” creating a skills gap that leaves millions of jobs unfilled because workers aren’t trained to do them, he said.

Members of the committee praised Rowe’s call to raise the public esteem of trade training and careers.

“I think it’s so important that we get that information out there in the public to offset what Mr. Rowe talks about, and that is helping to change the image of career and technical education,” said Virginia Foxx, the North Carolina Republican who chairs the Education and the Workforce Committee.

She continued, “I do think that we all have a responsibility to do that, all of us here, all of us in any part of education.”

Rowe found himself in the middle of a social media storm late last year when he objected to college students burning the American flag or asking for its removal from campus. “To my knowledge, no one has ever burned a flag at a trade school,” he wrote in a Facebook post that also dinged Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass., where the flag was removed, for charging steep tuition, funded for many students in large part by federal aid.

Rowe yesterday eschewed the traditional congressional uniform of suit and tie for a button-up shirt with reinforced elbows. He said there are a “thousand ways” to elevate career and technical training.

Officials should highlight programs like SkillsUSA, which sets up CTE competitions in schools, which Rowe called the best private example of a group working to “fill in that smoldering crater we created when we took vocational arts out of high school.”

He suggested something like the Keep America Beautiful campaign, a coordinated effort among corporate sponsors, individuals, nonprofits, and government entities that aimed to reduce litter on highways starting in the 1950s. It is best known for its memorable and successful “Crying Indian” ads in the early 1970s.

The same thing can happen for elevating work in the trades, but like the littering campaign, which took about a generation and a half to see results, it will take time, he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)