Designing Effective Remote Schools Requires Math: 3 Insights Into How Staffing Could Make All the Difference

Virtual school is undoubtedly an undesirable reality for the fall semester. So, its inevitability for many schools begs the need for a deep look at the math that may enable at least some students to come back to the classroom.

Critical for the new school year is a deep understanding among decision-makers for educational models that will best serve students. Once that’s in place, districts must also be able to figure out how their communities can design remote schooling now to facilitate a strong transition to at least some in-person instruction — especially for the most vulnerable students — when it’s safe to do so. And our research shows that the number of students whom districts can serve in-person will depend in part on insights gleaned from three important calculations.

Most districts now understand that a hybrid in-person/remote model can reduce group sizes by as much as half. But instead of looking at a transition from remote to in-person school as an across-the-board decision, understanding the math of such a transition could help schools get a lot more students back into the classroom earlier.

Insight 1: Existing teacher staffing levels matter — a lot.

The truth is, there’s a wide spectrum of staffing levels in American school districts, and those with a more robust staff to start will have more options to serve students in person at the smaller group sizes required for physical distancing.

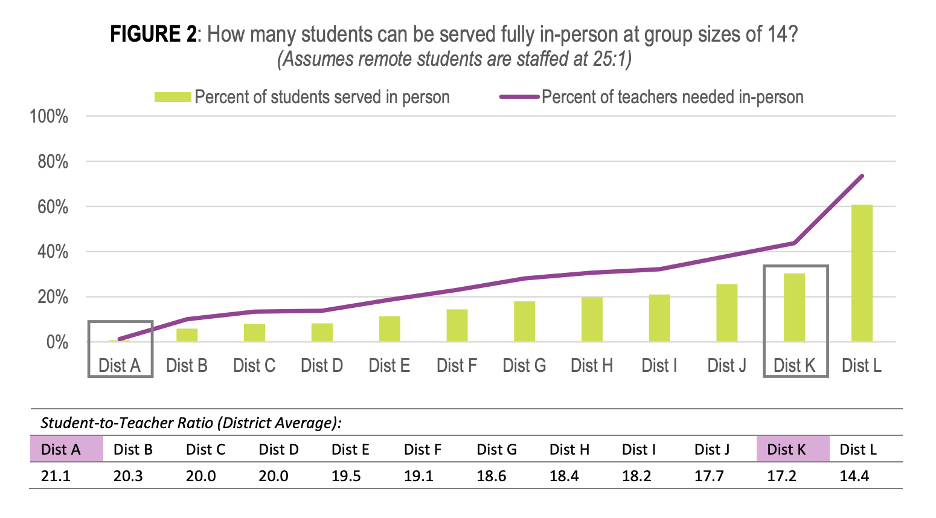

An analysis of 12 large school districts from Education Resource Strategies’ database of districts with whom we have partnered over the past few years shows why. These districts range in enrollment from 24,000 to more than 100,000 students and represent large urban and suburban districts nationwide. All these districts serve significant numbers of students who are low-income, students of color and students with special learning needs who would benefit the most from opportunities for safe, in-person instruction. Recognizing that context varies significantly across districts and schools, we start with assumptions of a five-day model, a target group size of 14 for in-person instruction to account for physical distancing needs, and a student-teacher ratio of 25:1 for remote instruction to mirror typical in-person classrooms.

Using these assumptions, we look at one district with a student-teacher ratio of 21:1 and find that they cannot feasibly implement a traditional five-day in-person model due to lack of staff. However, another district in our database with a student-teacher ratio of 17:1 could serve 30 percent of students in-person five days a week. That district could allocate resources for that 30 percent of students by prioritizing those who are most in need of in-person instruction. Variation exists across districts for students who are considered those most in need, but common characteristics include student in early grades, students with disabilities, students learning English and/or students who have not been effectively engaged in virtual learning. (This analysis focuses on the ratio of students and teachers in a general education setting only and does not include special education classes and other specialized instructional models where staffing ratios are much lower. The median district in our sample had a general education student-teacher ratio of 19:1, which corresponds to an average class size of 22 after accounting for planning time and breaks.)

In general, a positive difference of one in the average student-teacher ratio corresponds to about 8 percent more students who can be served in person. This amounts to approximately one grade level’s worth of students.

Insight 2: Strategic staffing of remote instruction can free resources for in-person school.

The more that a district can increase the student-teacher ratio for remote instruction, the more teachers will be available to offer in-person instruction in smaller group sizes when it’s safe to do so. Some remote instructional time could be in very large groups or structured as independent time. So, schools could still be able to provide small group and individual instruction despite higher remote ratios if they get creative with schedules and defining staff roles. Our analysis shows that with higher remote staffing ratios, districts with an average student-teacher ratio of 18 or less could feasibly bring back at least 50 percent of their students in person. That number could amount, for example, to all schools with higher-need populations or all students half-time.

Revisiting the example above, the district with an average student-teacher ratio of 17:1 can serve 30 percent of their students in person at a remote student-teacher ratio of 25:1. Our other example district, with an average student-teacher ratio of 25:1, would have to increase its remote staffing ratio to 37:1 to serve the same number of students in person. In both cases, increasing the remote student-teacher ratio up to 40:1-45:1 results in significantly more students who can be served in person, but our analysis shows that the value decreases significantly afterward.

Insight 3: More students can be served in person with greater flexibility in teacher and staff roles.

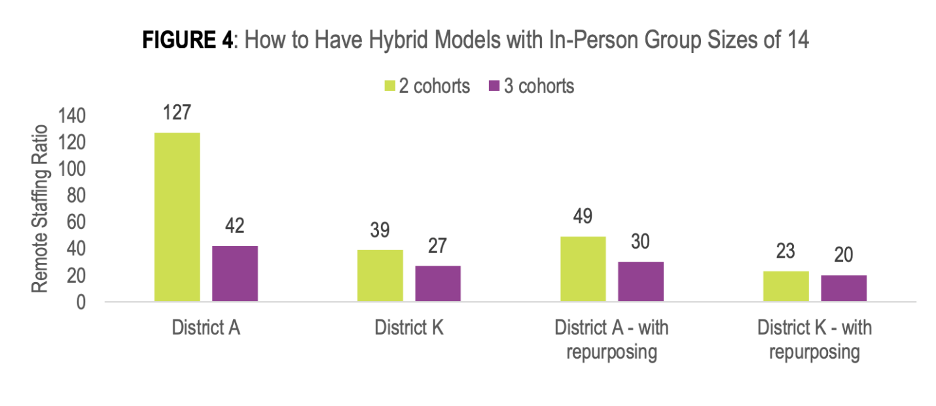

The types of roles that districts and schools have flexibility to change, and how much, will vary significantly based on local context such as common school staff positions, the specific combination of skills among staff and collective bargaining agreements. However, rethinking roles such as interventionists, aides and other instructional support staff can provide more opportunities for students to receive targeted support while freeing up homeroom teachers to lead core instruction.

As part of a hybrid approach, for example, support staff could supervise students on remote days, cycling through small groups throughout the day. This plan would reduce the number of core teachers needed for remote instruction and allow a larger number of students to receive targeted support. Alternatively, support staff who are in person can cover time that students are working independently to free up core teachers to spend virtual time with students who are learning remotely.

Taking our two example districts, we analyzed how instructional support roles would improve the trade-offs associated with a hybrid in-person/remote model. Our district that started with low teacher staffing levels is now able to offer a hybrid model with two cohorts at a much more reasonable staffing ratio for remote days (49 students per teacher, instead of 127). But even our district starting with higher teacher staffing levels is now able to use these roles to further improve the staffing model and student experience for remote days, or it could provide a more differentiated instructional model on in-person days.

Of course, we can’t forget that all this math is just a means to student learning and wellness. School districts must look at how they combine staff and organize instruction to help make up for learning losses, reconnect students with schooling and support students’ increased social and emotional needs. Exactly when a transition to any in-person school will occur will depend on public health conditions. But making informed decisions now about what these transitions might look like will increase the likelihood of getting back to in-person school in a way that meets the diverse needs of student and staff. Schools and districts should be designing remote models that enable smooth transitions to in-person instruction in smaller group sizes for physical distancing, take advantage of virtual formats and technology to extend the reach of core teachers, and flexibly use support staff to differentiate instruction in both remote schooling today and in-person schooling later.

Tiffany Zhou is a manager at Education Resource Strategies, a national nonprofit that partners with district, school and state leaders to transform how they use resources (people, time and money).

Jonathan Travers is a partner at ERS.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)