One of the most consistent criticisms of charter schools, recently

echoed by Hillary Clinton, is that they don’t serve the same students as neighboring district schools. To address this issue, some school districts have put in place

common enrollment systems, so that traditional public and charter schools are on even footing when parents are deciding where to send their kid.

Now new research shows that in Denver such a system has led more disadvantaged students to attend charter schools.

The first-of-its-kind study comes from Marcus Winters, a University of Colorado Colorado Springs professor and senior fellow with the Manhattan Institute, a right-of-center think tank. Winters examines Denver, which in 2012 moved from a school-based enrollment system — in which families had to apply to charter schools individually — to a single unified system that allows families to rank both district and charter schools by preference. A statistical algorithm then matches students and schools. The city also introduced “measures to assist parents, including publishing a school guide, sponsoring parent-resource centers, and creating a website to help parents compare schools,” according to the report.

The goal of such an approach: Simplify the enrollment process for families. In past research of New York City and Denver, Winters has found that charter schools served fewer special education students and

English-language learners than neighboring district schools — largely because those students were less likely to apply to charters in the first place. “The lesson then is if you want to address some of these gaps, you need to start thinking about how to get more kids to apply,” Winters told The Seventy Four.

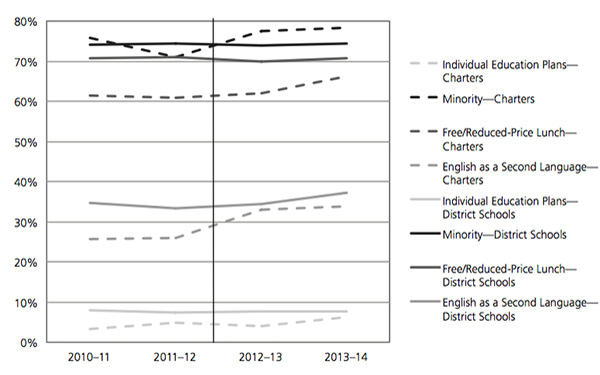

In his new study Winters finds the introduction of a common enrollment system in Denver succeeded in significantly boosting the number of students of color and English-language learners who ultimately attended charters. “After introduction of this policy you see some real reductions in these enrollment gaps” between charters and districts, Winters said. There was also a boost in the proportion of students qualifying for free and reduced price lunch who attended charters, though the results weren’t statistically significant.

There was no observed impact on special education students, which Winters attributes to the fact that the enrollment system did not apply to students with severe disabilities.

Entering kindergarten students, by classification and sector

Source: Manhattan Institute for Policy Research

Winters points to survey data from a separate study showing that after the introduction of common enrollment, parents in Denver were less likely to struggle or report difficulties with multiple applications and enrollment deadlines. (In New Orleans, though, the same study found that unified enrollment may have increased parental challenges with the application process.)

These findings provide suggestive evidence that a common enrollment system would help address disparities in charter and district school enrollments and could increase parental access to charters.

“The fact that a simple change to the application process made such a fundamental difference in the type of kid who’s applying to charters … means there is a pent-up demand under the current system among those kids,” Winters said.

The study, though, is significantly limited by the fact that it looks at just a single district with a relatively small charter sector.

The impact of a common enrollment system on student outcomes remains unclear. Winters said he didn’t study the question and that it would be empirically difficult to do so. Michael Johnston, a state senator from Denver, said in a recent interview with The Seventy Four that the introduction of common enrollment had led to “some small dips in those charter school performances, but the amazing part is they've now taken that as a challenge to come back with better and stronger effort.”

A few other cities, including New Orleans, Newark and Washington, D.C., have similar systems. Several other urban areas are considering such a system, though some are facing opposition from both ends of the ideological spectrum. In Boston and

Oakland, recent proposals to adopt universal enrollment processes have been pushed by charter supporters but opposed by skeptics of charter schools. On the other hand, some charter leaders worry that a universal enrollment system reduces their autonomy, Winters said.

Winters argues that common enrollment is the logical next step for improving access and equity for areas with successful charter sectors. “What I’m hoping is that this [research]… spurs a conversation within places that should be thinking about [a common enrollment system] a little more than they are — I think New York City is an obvious one,” he said.

;)