Demand For Preschool Is Growing In Hawaii As Federal Funding Dwindles

More families are set to receive subsidies to alleviate tuition costs, but the state is struggling to expand its early learning workforce.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

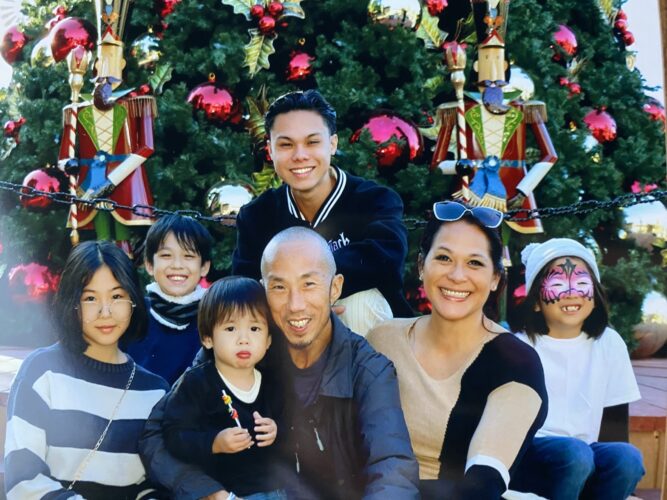

With five children, Malia Tsuchiya is no stranger to the high cost of raising a family in Hawaii. But with her 3-year-old beginning preschool this past October and her oldest son attending college later this year, Tsuchiya said her family finances are strained more than ever.

“It’s a heavy load to carry,” Tsuchiya said, adding that she currently pays $1,100 a month to send her youngest child to preschool.

The cost for many families will be reduced next year thanks to changes to the Preschool Open Doors program that expanded the criteria to qualify for state subsidies to include families with 3-year-olds and those making up to 300% of the federal poverty guideline. Previously, the program only helped to cover the preschool tuition of 4-year-olds and had more restrictive income requirements.

“The money that we’re saving is going to help us so dramatically,” Tsuchiya said.

The number of children qualifying for these tuition subsidies is projected to double this year, increasing demand for early learning as the state progresses toward its ambitious goal of providing all 3- and 4-year-olds access to preschool by 2032.

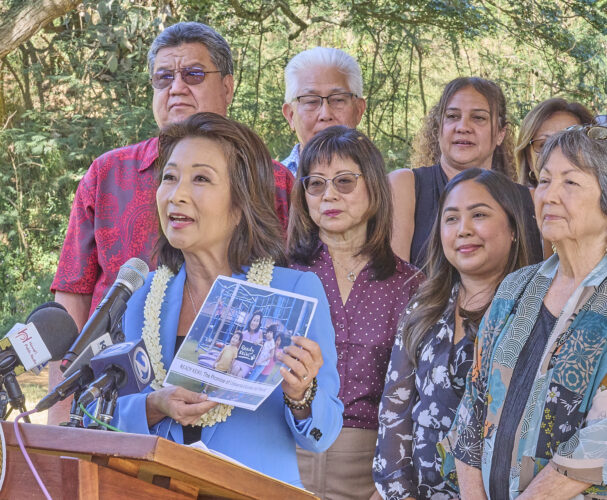

Currently, roughly half of Hawaii’s children do not attend preschool, according to Ready Keiki, an initiative introduced by Lt. Gov. Sylvia Luke to help the state achieve its 2032 goal.

Luke said the changes mean even a family of four making a household income of $100,000 could now qualify for a preschool tuition subsidy.

Federal Relief Funds Will Be Missed

According to the initiative, the state must create over 400 classrooms in the next eight years to ensure that all eligible children opting into preschool will have a spot at school. But the end of federal Covid-19 relief dollars could undermine the state’s efforts to expand its preschool sector.

The federal relief funds totaled over $110 million, with roughly $72 million expiring last November. The last of the funding, totaling $44 million, must be spent by September, according to the Department of Human Services.

The preschool sector was in a precarious place even before the pandemic, said Julie Kashen, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a New York-based think tank. The expiration of the federal relief funding means almost 130 child care programs, including infant-toddler centers and preschools, could close in Hawaii, according to a report Kashen co-authored.

The impact of lost funds might not be immediate, Kashen said. But, she added, if states fail to invest in their child care providers, some centers will start reducing staff and may eventually close all together.

While Hawaii has prioritized the expansion of preschool facilities in recent years, the state faces continued challenges with the recruitment and retention of preschool workers. Some providers worry that the end of federal funding will make it even harder to sufficiently compensate their teachers.

At Seagull Schools on Oahu, Chief Executive Officer Megan McCorriston said federal funding made all the difference for her staff by helping to supplement salaries during the pandemic.

“It really made them feel validated in their work in a way that wouldn’t have been possible without the additional federal funding,” McCorriston said, adding the funds also helped keep tuition relatively low at the schools’ five preschool and child care facilities.

The state provided over 3,000 child care employees with $2,500 bonuses using the federal funding, said Dayna Luka, child care program administrator at DHS. Over 600 providers also received funds to cover rent, payroll, professional development and other expenses.

The extra money was essential, McCorriston said, especially when Seagull Schools was enrolling fewer students than usual during the height of the pandemic. That resulted in less revenue for the school even as operating costs increased due to inflation, she added.

The federal relief funds stabilized the early learning workforce as much as possible during the pandemic, said Deborah Zysman, executive director of the Hawaii Children’s Action Network. According to DHS, the state’s child care workforce declined by approximately 30 providers from 2020 to 2022.

But, Zysman said, more investments are needed if the state wants to expand its preschool sector.

State Solutions Needed

Approximately 2,800 children could qualify for Preschool Open Doors tuition subsidies this year, Luke said. But there’s no guarantee that families will be able to find a preschool center enrolling new students.

Because of the workforce shortage, not all preschools are operating at full capacity, said Vivian Eto, strategy and project management lead for Early Childhood Action Strategy. She’s hopeful the Legislature can offer a solution this year.

House Bill 1964 would establish a wage subsidy for child care providers, ensuring a minimum of $16 an hour. A similar bill was introduced last year but died in the chaotic final hours of the session.

Rep. Lisa Marten, chair of the House Human Services Committee, said the subsidies proposed in the bill are intended to replace the expiring federal Covid relief funds.

“We’re hoping to pass that bill this session,” she said. “But there’s a lot of competing needs, including Maui, so there’s no guarantee.”

Yet, the state continues to push ahead in expanding its free preschool offerings. Currently, the Executive Office on Early Learning operates 49 public preschool classrooms with a total of 947 seats, said executive director Yuuko Arikawa-Cross. The state plans to add 130 classrooms by 2026 and complete a total of 231 classrooms by 2028, according to the School Facilities Authority.

While Zysman welcomed the expansion of public preschool facilities, she predicted that ongoing workforce shortages could pose some limitations. Pay tends to be higher for teachers in state-run preschools, and some private schools may lose their employees to the public sector, she added.

Paula Yanagi, executive director of Ka Hale O Na Keiki Preschool on Hawaii island, said she’s also lost some students to a public preschool classroom that opened at Honokaa Elementary School in 2014. While her enrollment has since recovered, Yanagi said, she wishes the state had first invested in community preschools like her own, especially in such a small, rural community.

But, Yanagai said, after the influx of federal funding for providers during the pandemic, she remains hopeful that the state now understands the importance of supporting preschools in years to come.

“I’m hoping this will just be the kickoff,” she said.

Civil Beat’s education reporting is supported by a grant from Chamberlin Family Philanthropy.

This story was originally published in civilbeat.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)