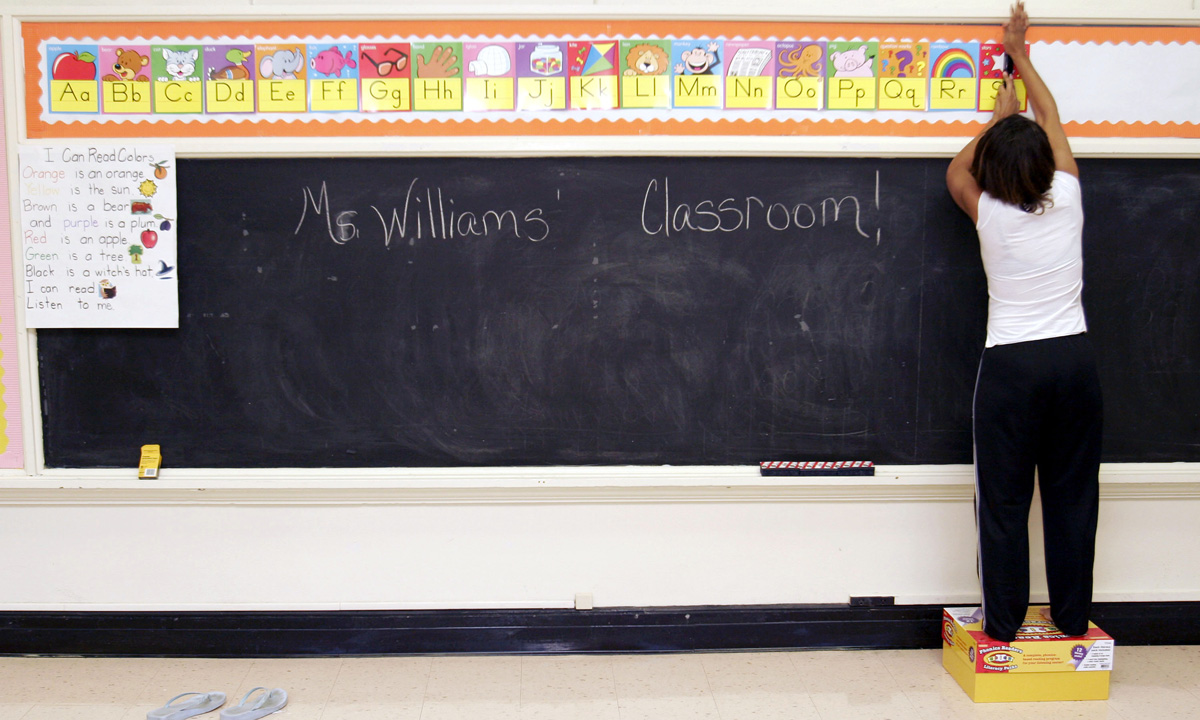

Delaware Schools Struggle to Fill Hundreds of Open Positions

The state has hundreds of open positions, including for teachers, at districts across the state with the school year just days away.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As Delaware’s families and students prepare for the start of the new school year later this month, many districts are still struggling to fill open positions before the summer ends.

More than 700 job openings remain unfilled at schools statewide, with an average of 41 openings per district, according to the Delaware Schools Consortium, which tracks openings across the state at all but four districts – the Appoquinimink, Cape Henlopen, Colonial, and Seaford school districts choose to do their own marketing.

The shortages experienced in Delaware schools are a continuation of a post-COVID trend, and it has led some districts to make more drastic changes.

Last year, the Capital School District serving the greater Dover area employed remote teachers to videoconference into some classrooms while a support professional managed students due to workforce shortages. In May, Capital district families were given less than two days’ notice that schools would shift to an entirely remote learning due to a shortage in teaching and transportation staff.

The Capital School District still has 124 job openings, and its same-school retention rates for teachers dropped by roughly 13 percentage points between the 2022-23 academic year.

Capital School District did not respond to Spotlight Delaware’s request for comment on its current needs. It is not alone in the need to bolster workforce levels though.

Brandywine sees the same amount of job openings as previous year

As of Tuesday, the Brandywine School District has 73 total job openings, according to the district’s Consortium page. District spokesman William “Bill” O’Hanlon noted that the number of job openings has been slightly higher than normal since the COVID-19 pandemic and that its 17 vacancies for elementary schools and 15 for its secondary schools are similar to where the district was at this time last year.

It’s almost like a domino effect.

BILL O’HANLON, BRANDYWINE SCHOOL DISTRICT PIO

Filling in the hiring gaps in the final weeks of summer is crucial because it’s important to ensure that buildings are well-functioning for its students, O’Hanlon added.

“When you have a school that does not have enough staff members to function adequately for student learning, I think that’s a concern for anybody,” he said. “At the end of the day, we want to make sure that there’s enough staff members in the building who are able to teach students.”

Staff at Brandywine usually speak with the administration before the end of the school year about whether they’ll be returning for the coming school year, which O’Hanlon feels gives the district a “leg up” on the hiring process. The district typically begins planning what its staff will look like for a future school year starting in the spring based on what students’ needs will look like for the following year.

O’Hanlon also noted the importance of looking at other areas besides educators, like cafeteria aids or custodial workers, who aren’t necessarily included when people think of shortages in education.

“If you don’t have enough cafeteria workers, that might mean longer lunch lines,” he said. “Longer breakfast lines might mean students who are going to be in the cafeteria longer and not in the classroom. If you don’t have enough custodians, again, it’s almost like a domino effect.”

Lake Forest experiences better recruitment year

Lake Forest had 16 job openings as of Tuesday, which is better than normal, especially in the last five years, according to Human Resources Director Travis Moorman. The district also had a same-school retention rate of 54.8% in 2022 and 52.7% in 2023, according to the state’s educator mobility data.

The Lake Forest School District also uses the Delaware Schools Consortium as its main resource, but Moorman noted although the consortium system is automated, it requires each district to have its own person to manage it.

One of the challenges Lake Forest experiences with the consortium site is that their collective bargaining agreement calls for a job to be posted for a specific amount of time.

After a job is posted, Lake Forest primarily relies on word of mouth to recruit and employ many people from the community as it is a smaller district. Like Brandywine, the district also begins planning for future school years starting in the spring. In some cases, Lake Forest is able to start hiring as early as April for the following school year.

In the past, Moorman has utilized regional job fairs as a way to recruit those who may be early in their careers but has seen an increase in recent graduates wanting to return to their home communities to teach.

“I have found, especially since the pandemic, that a lot of kids in college are more interested in staying home,” he said. “I’ll go to Pittsburgh to a regional job fair there. I’ve gone to Kutztown, gone to Millersville University, of course, we go down here to Salisbury and the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore, they usually do a combined job fair. But a lot of the kids, even down there at Salisbury, a lot of them are coming from the other side of the Chesapeake Bay, and a lot of them had plans to go back home.”

Given the difficulties in hiring through job fairs, Lake Forest has worked hard to recruit its staff through word of mouth or different connections.

“Our principals here in the district work really hard on recruiting people through connections and past work experiences,” Moorman said. “It’s really kind of a group effort. And this year, for the first time since the pandemic started, it’s really paid off.”

Woodbridge’s recruiters are its staff

Like Lake Forest, the Woodbridge School District, a small district serving the greater Bridgeville area, focuses on staff connections to help bring in new recruits.

“I would say our staff currently help us tremendously … by just discussing their work environment and how they enjoy it,” said Kelley Kirkland, the assistant superintendent at Woodbridge. “Obviously that piques the interest of other people that may not feel the same from wherever they are currently working.”

Woodbridge has maintained a steady same-school retention rate for its teachers in recent years, with a rate of 56.6% in 2022 and 55.7% in 2023. The district currently has 13 total openings, with two being at the elementary school level and one at the high school level.

Kirkland said the district is in “pretty good standing” with its amount of job openings, especially with teachers returning on Aug. 19. She credits the district’s standing with having a “really good” hiring season this past spring and summer compared to years past.

Although Woodbridge is seeing a good recruiting year, Kirkland has experienced the stress from trying to fill jobs in the remaining weeks of summer as she previously served as the principal of the high school.

“At the end of the day, teaching positions are tied to student performance and students that are reporting to our building, so when we have several teacher openings, it’s extremely stressful to think about how we’re going to welcome students back in several weeks, knowing that we don’t have all the positions filled,” Kirkland said.

Why the shortages?

During COVID, Delaware schools saw an uptick in teachers retiring that exacerbated workforce needs.

The state also has long faced staff competition for new teachers in the region, where traveling out of state to districts in New Jersey, Pennsylvania or Maryland is easy. As of the 2022-23 school year, Delaware ranked 16th overall in average annual educator pay at nearly $69,000, according to the latest national survey by the National Education Association.

However, neighboring states ranked seventh (N.J.), ninth (Md.) and 11th (Pa.) in average pay, offering $5,000 to $7,000 more than Delaware. Those averages are particularly impacted by first-year teacher salaries where Delaware has lagged behind by even more.

In response, Gov. John Carney has prioritized teacher salary increases, starting a proposed four-year investment this year to push starting teacher salaries in Delaware to a minimum of $60,0000.

Finally, teacher shortages come at a time when state educators are expressing frustrations within schools too.

The Delaware State Education Association (DSEA), the union that represents state public school teachers, recently conducted a survey with its members to determine the main issues of the teacher shortage. It found that seven out of 10 teachers are dissatisfied with their teaching conditions.

“One of the concerns that does come up from members frequently is concern about student behavior in classrooms, and what we can do to address that,” said Jon Neubauer, the director of education policy at DSEA. “I think, mostly from the perspective of our members, we want every child in our schools to be successful, so we know that if there are behavioral issues that need to be addressed, addressing them only improves academic outcomes for the students.”

In response, the state recently established a Student Behavior and School Climate Task Force that is examining the state of Delaware schools and what can improve from a behavioral aspect.

New programs aim to help

DSEA has been working at the state level to identify programs, supports and resources to encourage professionals to stay in Delaware’s school.

Select school districts in the state — including Appoquinimink, Brandywine, Caesar Rodney, Cape Henlopen, Capital, Colonial, Indian River, Milford, Seaford and Smyrna, as well as Academia Antonia Alonso Charter School, the Las Americas Aspira Academy and Campus Community Charter School — also have access to the students enrolled in Delaware Technical Community College’s Bachelor of Science in education program.

Students enrolled in the program participate in a year-long residency program, where they gain professional development with a teacher starting at the beginning of the school year.

“It’s a co-teaching experience through the end of the school year, so they see the ins and outs of a school year, and that’s including report cards, parent conferences, field trips, decorating a classroom in the beginning of the school year, to parties, you name it,” said Jill Austin, the program’s director. “All of the ins and outs of the school year are much more beneficial to a student because and you build that rapport, you get to see the growth, the academic growth and the social, emotional growth of your students from the beginning of the school year to the end.”

Del Tech has been working with external stakeholders and with school districts to establish a good rapport, and the stakeholders have told the college which schools need the program’s residents, Austin said. She also has districts reaching out and asking for more residents as well.

The college is also implementing a “grow your own” program, which allows them to bring in vetted paraeducators for a three-year obligation to complete their degree in three years and become a “teacher of record” by 202, Austin added.

This story was originally published on Spotlight Delaware

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)