Deep in South Carolina’s ‘Corridor of Shame,’ Teachers at New Tech Network Strive for a Big Turnaround

Walterboro, South Carolina

Outside the massive new school with its calming fountain and palm trees, teacher Brooke Hite hopped a yellow school bus and braced for a long ride. New to the community at the start of the last school year, Hite hadn’t yet met any of her students, but on that hour-long bus trip, she found insight into their lives.

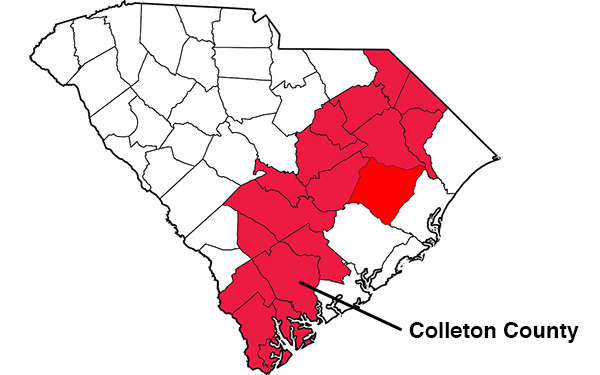

For most Colleton County High School students, life doesn’t mirror their picturesque school. Along country roads that snake through dense forest and swampland, Hite found staggering income inequality. Three-story homes with massive white pillars — reminiscent of the days when rice plantation owners struck “Carolina Gold” — contrasted with rusted trailer homes next door. In Colleton County, the median annual household income hovers near $33,000, about a quarter of residents live in poverty, and only 14 percent of adults have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Colleton County is located in southeast South Carolina, part of a poor, rural region along Interstate 95 branded in a documentary as the “Corridor of Shame” for historically inequitable school funding and poor student achievement.

Hite could have made $5,000 a year more teaching geography in a wealthier neighboring district, she said. But in Walterboro, she saw opportunity. Colleton County High School is home to the Cougar New Tech Entrepreneurial Academy, a business-focused school-within-a-school that is an outpost of the New Tech Network, a national nonprofit that has partnerships with nearly 200 schools across the country, including 12 in South Carolina.

The network boasts a high school graduation rate of 92 percent — about 9 points higher than the national average — which it attributes to what it calls a “deeper learning” approach to education.

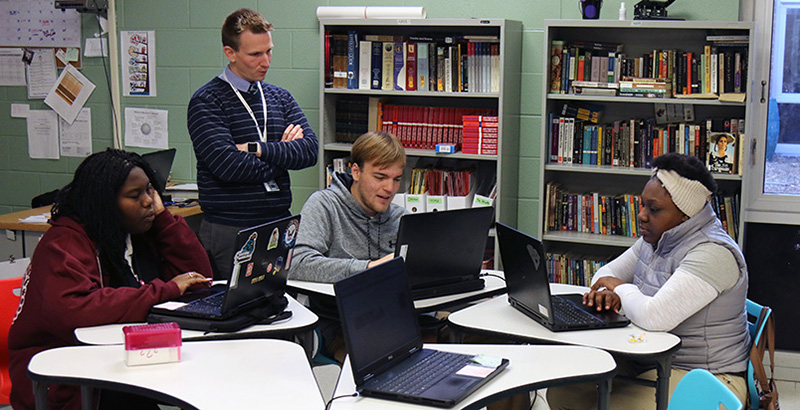

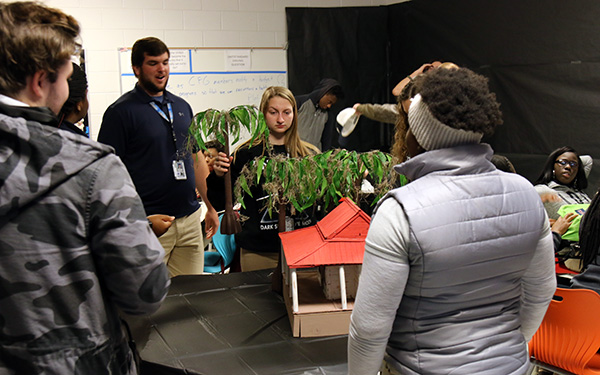

New Tech puts a laptop in the hands of every student and trains teachers to build their classrooms around group projects that require critical thinking and collaboration. Students are evaluated on skills such as oral communication, collaboration, and agency, in addition to academic performance. Physical space is crucial to New Tech’s model: Teachers work in pairs, so large classrooms are needed. Students don’t sit in rows and digest prepared lectures; instead, classes buzz with chatter from kids facing one another in clusters of desks.

All these efforts come together in service of one overarching goal: relevance. If the course material connects to kids’ lives outside the classroom, the network believes, students will become more engaged in their learning, ultimately boosting high school graduation rates, college attendance, and employability.

“With the technology and the relevance and the community connections, it just really appealed to me,” Hite said. “I never even saw the school, I just heard about the program.”

A wholesale reinvention

New Tech was launched in 1996 with a single high school in Napa, California, by a group of entrepreneurs who believed local schools were not adequately preparing students for the workforce. Now the network operates in 27 states and Australia, with 72,000 students and 4,400 teachers.

Two-thirds of the schools are in low-income communities, and 60 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch; 42 percent are white, 23 percent are black, and 27 percent are Hispanic — a minority student population above the national average.

Some New Tech schools, like Napa’s, were built from the ground up, but more commonly, the network partners with districts to do a full-school conversion or create a school-within-a-school, as in Colleton County, typically under a four-year contract.

Furman University’s Riley Institute helped bring New Tech to South Carolina for its ability to raise academic achievement in districts with high poverty and low graduation rates, said institute executive director Donald Gordon.

“We homed in very quickly on the New Tech Network,” Gordon said. Other New Tech schools across the country, he said, “were graduating kids at a much higher rate than traditional public schools with the same demographics, and in addition to that higher graduation rate, there were a substantially larger number of kids that were going on to higher education.”

Unlike a lot of reform efforts, which focus on one innovation at a time, like technology integration or block scheduling, New Tech tackles the entire school structure simultaneously, said Paul Curtis, a founding teacher at New Technology High School in Napa who is now network curriculum director.

“Too many school leaders falsely believe you can’t handle too much change at once,” Curtis said. “If you only try to change one piece of a complex organization, that one change doesn’t fit with the rest of the structure and so the system tends to hate that change. What we’ve learned is that really what you want to do is reinvent the whole thing at once.”

In Colleton County, that meant knocking down walls — literally — in the new high school to create larger classrooms where co-teachers could work together. Then it meant finding teachers who were willing, and able, to share their space, lessons, and authority. Applicants, initially drawn from the high school’s pre-existing teaching staff, were selected to join the program after successfully demonstrating collaboration during job interviews.

For math teacher Jennifer Shipp, who joined Cougar New Tech when it opened in 2013, there was a steep learning curve. Having a “type A personality,” she said, she worried about having to collaborate.

“I liked the person I was co-teaching with my first year, but having to plan something with someone else and having to listen to someone else’s opinion, it’s like, ‘I want to do it my way,’ ” she said. “So that was tough. I had to learn how to work with someone else.”

Hite, though, found that New Tech’s culture of collaboration made her first full-time teaching job easier. Through a “critical friends” process, educators receive constructive feedback on classroom project proposals, and as she adjusted to the job, her co-teacher was a valuable resource. Still, in one of Hite’s classes, which combined English 2 with Advanced Placement human geography, developing coursework that satisfied the rigor of both subjects proved to be a big challenge.

“It’s very difficult to do cross-curricular things,” she said, “because they’re both so heavily content-focused, so it’s about finding that balance.”

Throughout a 4½-year implementation process, New Tech gave Colleton County teachers 600 hours of professional development and coaching, a proprietary learning platform, course materials, and other online tools, according to the Riley Institute.

The approach trains teachers to immerse students in a project-based learning approach that empowers them to discover aspects of themselves that could go unnoticed in a traditional setting, said Lydia Dobyns, network president and CEO.

“We as humans are not built to sit and be quiet and consume information for eight hours and expect that that’s going to really invite us in to be an active learner,” she said.

The ‘McDonald’s test’

Concerns about career readiness and graduation rates echo throughout Walterboro and the surrounding region, technically known as the Lowcountry, where job training among locals has struggled to keep up with the region’s growing manufacturing and technology sectors. Though 85.2 percent of Colleton County High School students graduated in 2016, 66.4 percent of the graduating class enrolled in a two- or four-year college. In 2017, the school’s graduation rate inched up by about 1 percentage point.

Schools are a reflection of a community’s economic prospects, and Walterboro doesn’t pass the “McDonald’s test,” said Joshua Cable, former director of Cougar New Tech. Cable, who is now assistant principal at a school closer to his hometown, knows fast food: He worked at McDonald’s in high school and college. If an older adult is behind the register at 5 p.m. on any given day, he said, it’s a foolproof sign an area lacks high-paying jobs. Although the region’s economy saw an uptick last year, driven in part by a new Boeing airplane plant, Cable said his students still have to compete with older residents for service jobs.

Melissa Crosby, who oversaw New Tech’s launch at Colleton County and is now principal of the entire school, recalled how Cougar New Tech’s first freshman class, like many Lowcountry students, struggled with reading — and with school in general.

“Our students don’t read well, and not reading well can manifest itself in a hundred ways — obviously in your test scores and your scores in your classes, but it can also manifest itself in your behaviors,” she said. “By the time kids get to high school, you see a high population of students who not only have reading challenges, but they have behavioral challenges. You know, it’s, ‘I don’t really know how to read, so I’m going to try to detract from that behavior by doing this.’ ”

Of the program’s first 80 students, Crosby said, about a quarter read between a second- and sixth-grade level. So, to raise student reading performance, New Tech teachers incorporated reading and writing techniques in all projects in every class.

“That’s how those teachers propelled those students, because they realized that they weren’t prepared for us,” she said.

A social studies teacher at the time, Cable said he incorporated grammar, the writing process, and proofreading into his group projects. In math classes, teachers emphasized word problems, which students often skipped over.

While similar techniques could be used in general classrooms, Cable said, New Tech’s culture of collaboration helped spur teachers who typically don’t focus on improving students’ English skills to incorporate that work in their classrooms. Those skills are particularly important for New Tech students because the network’s emphasis on project-based materials requires better reading comprehension.

“It was easier to explain to people that it does relate to you because we would see how the literacy struggles affect the learning in all classrooms,” Cable said. “It was easier to see in this environment how important it was to get kids up to speed on reading level. That way, they could take on the higher-level material.”

At Colleton County High, where 73.4 percent of students live in poverty, about half passed the state’s end-of-course math exam last year, according to state data, and 61 percent passed the English exam. Among Cougar New Tech students, however, 82 percent of students passed the math exam and 83 percent passed the English exam, Cable said, which exceeds the state average.

All South Carolina students are required to take the ACT in their junior year, and this year’s Cougar New Tech graduating class saw a similar test score advantage: Their results mirrored the state average, while the remaining Colleton County students lagged behind.

‘Corridor of Shame’

New Tech’s journey to Walterboro, a small town filled with cheap chain motels and fast-food joints, is a chapter in a long story involving decades of racial discrimination, inequitable education funding, legal battles, a documentary, and former governor Dick Riley.

Even in a state that ranked 37th in the nation on an Education Week analysis last year, students in the Corridor of Shame stand out for poor academic performance, and debates over inequitable education funding in the corridor have raged for decades. In the 1940s, Clarendon County deemed it unfair to provide African-American students with school transportation because their parents paid little in taxes, so the kids would have to walk — some, as far as 10 miles. That argument helped spur a lengthy legal fight that ultimately became a foundation for the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling.

In the early 1990s, a decision by lawmakers to force poor districts to pay for transportation and employee benefits led to a school funding equity lawsuit that played out in the courts for more than 20 years, said Bud Ferillo, producer and director of the Corridor of Shame documentary, who served as Riley’s deputy lieutenant governor from 1982 to 1987.

The 36 plaintiff districts had an 86 percent poverty rate and were 88 percent minority. In one school, only four of 10 drinking fountains worked. In another, raw sewage backed up into the hallway. At one school library, books dated from the 1930s and ’40s, including one text with a bold proclamation: “One day, man will land on the moon.”

“You turn on the computers, some of them say ‘for use by inmates only.’ That’s because the computers were contributed by the local Department of Corrections,” Ferillo said.

Colleton County’s “separate but equal” school system persisted for years after Brown. In 1970, in response to a federal civil rights complaint, a district court judge ordered the county to abolish its race-based dual education system. Then, in 2001, the parents of 10 African-American students who attended predominantly black Ruffin High School sued the district for failing to eliminate racial segregation. A year later, the district merged its two high schools, Ruffin and Walterboro High School, and established Colleton County High School. The federal government granted the district “unitary status” in 2004, declaring it effectively desegregated.

That same year, author Pat Conroy — who once taught in a poor, remote coastal South Carolina community — served as grand marshal at an education equity rally at the state capitol in Columbia. That event, with its thousands of demonstrators, inspired Ferillo’s documentary.

Today, Colleton County High School, built in 2011, serves all 1,600 students in grades 9–12 in the district, and the school demographics are closer to a reflection of the county: 47 percent of students are black and 45 percent are white, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Chasing results

Soon after New Tech opened its first outpost in Napa, Riley — having moved from South Carolina governor to U.S. secretary of education for then-President Bill Clinton — visited the school and liked what he saw, particularly the focus on jobs and classwork relevant to students’ lives. He joined the board of KnowledgeWorks, which at the time was New Tech’s parent organization, and in 2011 KnowledgeWorks and the Riley Institute at Furman University — his alma mater, which named the institute for him — applied for a $2.9 million federal Investment in Innovation Grant to bring New Tech to the state.

The goal was to develop New Tech schools in “two of the nation’s most economically underresourced rural communities,” according to the institute, to boost student performance, close achievement gaps, and decrease dropout rates. They chose Colleton County and Scott’s Branch High School — the Clarendon County school that played a pivotal role in Brown — 54 miles away, up I-95. The idea was to place New Tech in one large high-poverty rural school and one small one to serve as models for expansion to other schools in the state.

With Colleton County High School already divided into four mini-schools, New Tech moved into a space previously occupied by a business program and started knocking down walls. All interested students could sign on, in an open enrollment process that continues today.

From that initial group of 80 kids in 2013, Cougar New Tech’s student body has grown to about 350. The program graduated its first senior class last school year — with 100 percent of Cougar New Tech students receiving their diplomas, compared with 86 percent across the entire school. For Crosby, the graduation rate speaks for itself. This school year, she expanded New Tech’s footprint at Colleton County High and launched the Health Careers Academy, designed for students interested in pursuing jobs in the medical field.

“To say that you can take students in four years who read at a second- to sixth-grade level and graduate all of them, then what you’re saying is that it is possible,” she said.

As New Tech grows in Colleton County and in other districts across the country, a 2014 report by the American Institutes for Research found that “deeper learning” networks are linked to better outcomes, improving student cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal competencies — including among low-income students and English language learners.

Along with better test scores in reading, mathematics, and science, researchers found that deeper-learning schools boast high school graduation rates 9 percentage points higher than schools with comparable student populations — consistent with New Tech’s results for the network as a whole. The studies compared deeper-learning network schools to others that hadn’t adopted the approach; sample sizes were not large enough to compare networks with one another, said senior researcher Kristina Zeiser.

Although the “deeper learning approach” didn’t increase college enrollment or persistence rates, graduates are more likely to attend four-year institutions, including those with selective admissions, researchers found.

“The significant impact on attending college was only significant for lower-achieving students,” Zeiser said. “If they attended a ‘deeper-learning’ network school and were lower-achieving, then they were better off and more likely to go to a four-year college than a lower-achieving student at a comparative school. But when looking at the higher-achieving students as defined by above the state mean, there was no difference — they were all going to go to college anyway.”

Relevance in the classroom

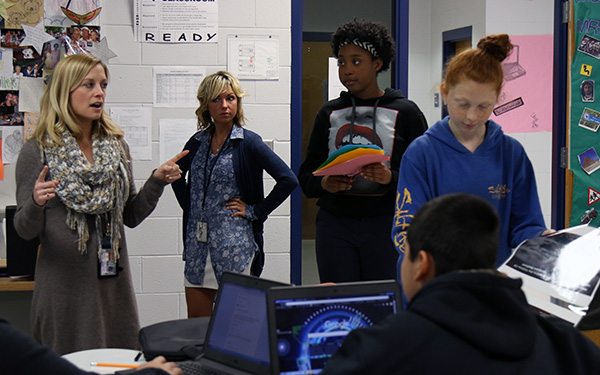

Is public education free and equal? That’s the question Hite and co-teacher Lydia Culler posed to a class of freshmen last school year. In a course combining geography with English I, students were exploring education in their community and — in keeping with New Tech’s mandate for relevance — reflecting on their own experiences. As part of the project, students read The Water Is Wide, which highlights education inequity in rural South Carolina.

The book, later adapted into the movie Conrack, is loosely based on Pat Conroy’s stint as the only teacher in a two-room schoolhouse in the 1960s on South Carolina’s remote Daufuskie Island, where the poor, predominantly African-American community faced stark education challenges: Most of his fifth- through eighth-grade students read below a first-grade level, and some couldn’t recite the alphabet.

The class also watched the documentary Rich Hill, about growing up poor in a rural Missouri town with nothing to do — an experience that Hite, who is now pursuing a graduate degree in psychology, said resonated with her students.

In the documentary, kids “lost all interest in their education, and so they were dropping out and they were facing things like their parents, who had serious medical issues, and themselves, who were doing drugs or using profanity, which are some issues that sometimes arise in a community like that and a community like this,” she said. “They were able to draw so many connections between how these kids were similar and use that as a motivator to be like, ‘Well, we can do better than that.’ ”

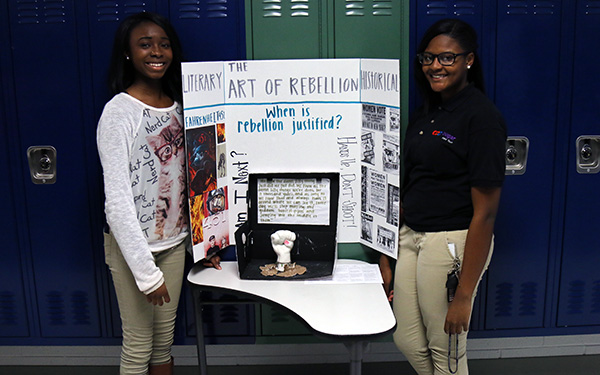

The project concluded with the students creating “public service announcements” about South Carolina’s education system and their own school experiences. Using videos as their primary medium, some students offered suggestions for additional resources their schools and community could use, while others reflected on the opportunities they were given.

Like New Tech.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)