DeAngelis & Burke: What If Vouchers Came With More Freedom for Public School Leaders? Our Research Shows They Still Wouldn’t Go Along

In 2005, NBC premiered a show called Deal or No Deal. Contestants could win big money — up to $1 million — if they selected the one briefcase out of 22 (which ranged in value from 1 cent to $1 million) that contained the big bucks. Along the way, different monetary amounts would be revealed one by one in the briefcases, providing the contestant with more information about the amount of money that might be inside.

Enter the banker. With additional information came additional temptation. The banker would offer to buy the briefcase for some amount of money. When the contestant would refuse to be bought out (in hopes the suitcase contained a higher amount), host Howie Mandel would enthusiastically exclaim: No Deal!

Traditional public school employees tend to shout No Deal! and oppose private school voucher programs. This could be explained by risk aversion, concerns over equity and inclinations to stifle competition. Whatever the reason, opposition to school vouchers is explained by expected costs exceeding expected benefits in the minds of public school employees.

But is it possible that private school choice would have a better chance of passing if enacted alongside additional benefits for public school leaders? And would school choice advocates and opponents actually be able to strike such a deal?

Our just-released study suggests that deal would be unlikely.

In theory, giving public school leaders more autonomy alongside enactment of private school choice programs might make them more inclined to support the change. After all, deregulation of public schools would allow them to more effectively compete with nearby private schools. As the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District recently said, “[If] it’s the flexibility of charter schools that’s allowing them to excel, let’s bring that flexibility into the traditional school classroom.”

We conducted a survey experiment to examine the effects of public school deregulation on actual public school leaders’ support for a hypothetical private school voucher program in California. We randomly assigned one of four types of deregulation to leaders of 7,127 traditional public schools in California in early 2019 and then asked whether they would support a hypothetical voucher program in their state.

The survey asked, “Would you support a new private school voucher program in California (available to all students in the state) next year?” The control group received a note saying state requirements of their public schools would not change. The experimental groups received notes saying that their schools would no longer need to adhere to one of four regulations: administering standardized tests, reporting the results of standardized tests, hiring certified teachers and providing transportation for all students.

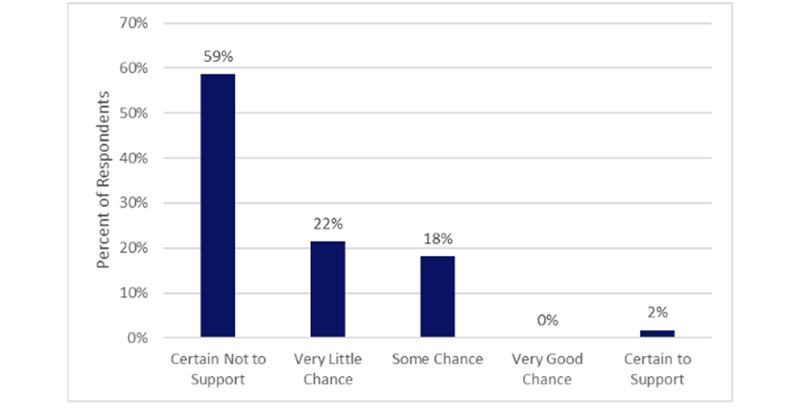

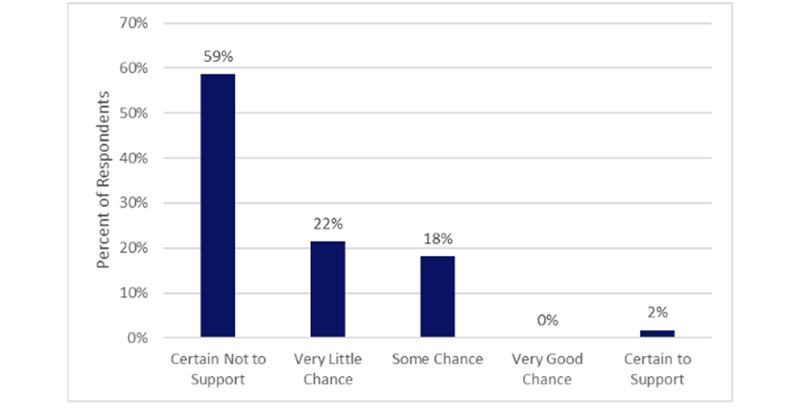

We received responses from 755 public school leaders in California. Our findings, like those of a 2018 EducationNext poll, were that public school leaders were largely unsupportive of the hypothetical private school voucher program. In fact, 59 percent of the respondents in the control group said they were “certain not to support” the program. Twenty-two percent said there was “very little chance” they would support the program. Less than 2 percent said they were “certain to support” the program.

Figure 1: Distribution of Public School Leaders’ Support for Private School Vouchers in California

We did not find any statistically significant effects of deregulation overall on public school leaders’ support for the hypothetical private school voucher program. This finding can be explained in two ways: (1) the perceived costs of additional competition from private school voucher programs far exceeds the perceived benefits of additional autonomy for public school leaders in California, or (2) the randomly assigned “benefit” of additional public school autonomy also comes with additional costs — autonomy could mean more work for the public school leaders in terms of adjusting to the new regulatory environment and additional responsibilities.

Surprisingly, however, we did find that depending on school size, certain types of deregulation do reduce public school leaders’ support for the hypothetical program.

Specifically, we found that no longer requiring large public schools to administer state standardized tests increases the likelihood that public school leaders will be “certain not to support” the hypothetical voucher program by about 21 percentage points (36 percent). In addition, no longer requiring large public schools to hire state-certified teachers increases the likelihood that public school leaders will be “certain not to support” the hypothetical voucher program by about 17 percentage points (29 percent).

These significant results can also be explained in two ways: (1) larger public schools might face more substantial costs associated with transitioning to new competitive environments than smaller schools, or (2) larger schools may disproportionately benefit from the existing regulatory environment if it stifles competition.

Our study has important limitations. The response rate was only 10.6 percent, so our results might not be representative of the entire state. Findings might also differ in other states and for other types of school employees, such as teachers. In addition, the results are based on survey responses about a hypothetical voucher program; public school leaders might respond differently to a real program.

Much more research on the topic is needed. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that, although there may be merit in such policy, deregulating public schools will not increase their leaders’ support for private school vouchers in California. Indeed, leaders of some public schools might view certain types of deregulation as additional costs rather than benefits. Of course, these results do not mean that deals cannot be struck between school choice advocates and critics. As such, both groups should continue to look toward ways to work together to make education better for all children, regardless of what type of school they attend.

Frequently, the Deal or No Deal contestant who refused the banker’s offer would end up worse off than if he or she had taken the deal. Policymakers might consider that they are leaving school districts worse off by limiting choice and maintaining high levels of regulations. At least for now, however, public school leaders are shouting No Deal!

Corey A. DeAngelis is director of school choice at the Reason Foundation and an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute. Lindsey M. Burke is director of the Center for Education Policy and Will Skillman Fellow in Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)