D.C.’s Missing Students and the Rush to Avert a COVID Classroom Crisis

Thousands of the city’s littlest learners were missing from schools last fall. As they now begin to return to classrooms, all at varying academic levels, how will educators handle the fallout from the pandemic’s K-shaped recession?

By Beth Hawkins | August 8, 2021

On May 22, 2020, heading into a holiday weekend that would, in non-pandemic times, draw throngs to the National Mall’s monuments and museums, Washington, D.C.’s positive COVID-19 test rate was the highest in the nation. Accordingly, Mayor Muriel Bowser extended her city’s shutdown order.

On the surrounding streets, businesses were shuttered or operating at vastly diminished capacity. Food trucks that normally feed families touring on a budget — and, by extension, feed the families of the people who own the trucks and cook the food — were idled. Steakhouses were echo chambers. Underground, DC Metro cars ran empty.

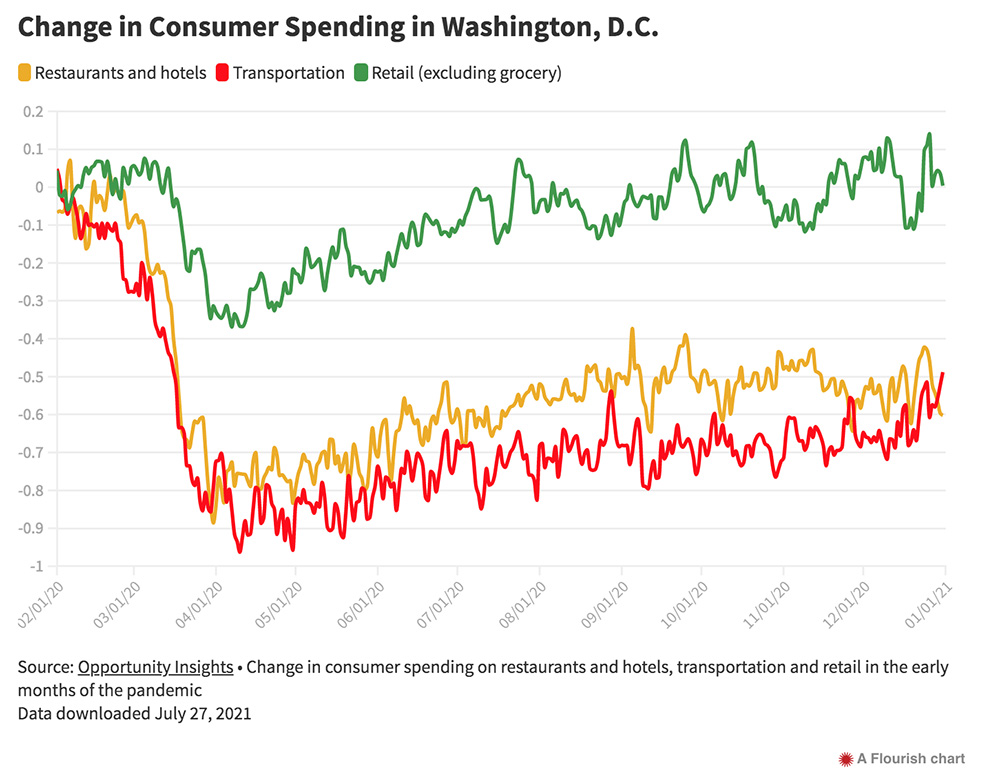

It wasn’t just the lack of tourists. Half of D.C. residents can do their jobs from home, the third-highest rate in the nation, and those high earners had been cutting back on spending for weeks.

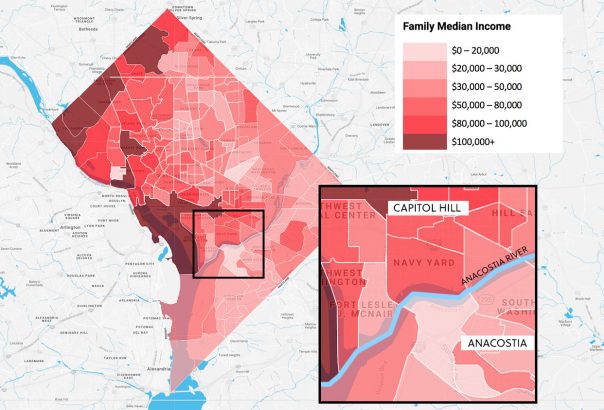

When residents of the Capitol Hill neighborhood, where median household income is $126,000, stopped shelling out for lunches and happy hours, for example, small business revenue downtown plummeted by 86 percent or more.

Safe at home, these high earners had the lowest COVID-19 death rates.

In nearby neighborhoods — across the river in Anacostia, for example — it was a totally different story.

The new frugality among the city’s rich took money, literally, from the pockets of their neighbors in the city’s southeastern neighborhoods, where median income crests at $36,000. But in those wards, the poorest in the city, whose residents were unable to work from home — if they still had jobs — spending stayed constant or even rose, a sign there were no luxuries to cut.

In fact, credit card use and other forms of borrowing by D.C.’s lowest-income households rose 17 percent early in the pandemic, worrying economists who fear people are going into debt to pay for basic necessities — the start of a financial tailspin that often leads to homelessness.

When economists talk about the pandemic recession being K-shaped, this is the divide they mean. Instead of a typical recession’s V — everybody dips and recovers relatively uniformly — D.C. residents at the top of the K have simply shifted their spending, from consuming services provided by their low-income neighbors, at its bottom, to ordering Pelotons and standing desks.

When the pandemic recession struck, economists John Friedman and Raj Chetty realized it looked different from previous downturns. While even small changes in the way money changes hands create ripples, COVID was a shockwave. The co-founders of Opportunity Insights — a team at Harvard University that researches income inequality and education’s potential to lift children out of poverty — persuaded credit card companies, payroll processors and other businesses that track money as it moves through the economy in real time to turn over what are essentially trade secrets. Using that information, the researchers built a nationwide online pandemic tracker capable of providing a down-to-the-day snapshot of who is spending and who is struggling, by income level, city, state and county and, in some instances, by zip code.

The data quickly revealed stunning implications on virtually every front.

Affluent Americans at the top of the K bounced back right away — much more quickly than in a typical recession. But their new spending patterns crippled the businesses that supported their lower-income neighbors; those impoverished families on the bottom continue to struggle disproportionately on every front, beset by challenges long proven to be detrimental to children’s ability to learn in school.

(Friedman and Chetty update the tracker as the underlying information changes. The data in this story was downloaded June 29, 2021.)

The Opportunity Insights tracker contains one academic dataset: student participation and progress on the math app Zearn, which one-fourth of the nation’s K-5 students have access to. Immediately after schools closed, use of the app among low-income students “completely dropped off,” notes Zearn CEO Shalinee Sharma. As they started logging on again, a yawning gap became apparent. A year into the pandemic, these students’ progress was behind where it should have been, while their wealthier peers were ahead 28 percent.

New studies by McKinsey & Co. and the nonprofit assessment concern NWEA found wide disparities between white/affluent students and their low-income peers/children of color. Depending on grade and subject, low-income students ended the 2020-21 school year with up to seven months of unfinished learning.

Researchers, Friedman told The 74, fear the resulting losses — of jobs, of mental health supports and reliable food supplies — may have even more devastating impacts for children that schools were already failing to serve, with education’s potential for lifting a family out of poverty moving further out of reach.

Compounding the inequity is a chilling racial disparity in the pandemic’s death toll. Blacks, who make up half of D.C.’s overall population, represent 94 percent of residents southeast of the river — and in May 2020 were 80 percent of COVID-19 deaths, Bowser noted as she extended the shutdown.

Another disparity: In the weeks before D.C. Public Schools called an early end to the academic year, low-income students were absent from distance learning at much higher rates than affluent children. On Capitol Hill, parents hired tutors and downloaded educational games to keep their kids engaged. Across the Anacostia River, as the stresses borne by their parents compounded in the pandemic, many kids disappeared from their online classes.

WATCH: Beth Hawkins details her latest investigation into COVID’s K-shaped recession and how the fallout will challenge America’s schools

By the start of the 2020-21 school year, it was clear the city’s missing students weren’t just disproportionately the poorest — they were also the littlest. Though the numbers would fluctuate throughout the year as families’ circumstances shifted, kindergarten enrollment was down by more than 500 students over projections, and by 1,800 in D.C.’s publicly funded preschools for 3- and 4-year-olds. Even before the pandemic, only half of U.S. 5-year-olds were considered kindergarten-ready. The number unprepared doubtless is much higher now.

Which raises the question: When this year’s missing 4- and 5-year-olds show up for kindergarten next year, they will be both far ahead and far behind — in some places, in the same classrooms. How will D.C. schools meet their needs?

With a little help from a gumball machine

In March 2020, the pandemic claimed Natalya Walker’s last side hustle. She had been cleaning houses, but suddenly that was unsafe. Scared at first into wiping down their mail and groceries, her affluent clients decided overnight to scrub their own bathrooms.

Walker was pretty good at patching gigs together. She was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2018, but before that she clerked in grocery stores, drove a limo and entertained kids at Gymboree. Once officially declared disabled, she found cleaning homes for cash was her best option for supplementing her meagre income. Since she didn’t work a formal job, when COVID-19 shuttered Washington, D.C., she didn’t draw unemployment benefits.

Housecleaning gigs on hold, Walker bought four small gumball machines and looked for places to set them up where there was still foot traffic. A city council candidate let her put two in his campaign headquarters, one stocked with gum and one with nuts. For a while, she could count on $5 to $10 in quarters every time she checked them. She gave the other two to her 18-year-old, Brian Clark, to supplement his pay from his job working on a garbage truck.

Walker’s other son, 4-year-old Mustafa Fletcher, lives with her in a battered public housing complex in Anacostia in Ward 8, the city’s most impoverished section. As grim as the economic statistics are for the area as a whole, for Walker’s census tract, they are worse. Median household income is less than $20,000 — but economists have long known that traditional data underestimates the impact of financial crises on people in neighborhoods like Anacostia, who are disproportionately dependent on public benefits and less likely to show up in unemployment statistics. One in five children who grow up there will not leave.

Still, with its dense concentration of kids, Walker’s neighborhood is home to a number of schools and community organizations offering universal, full-day pre-K, which the District of Columbia offers for free to 3- and 4-year-olds regardless of family income. In 2017, 90 percent of D.C. 4-year-olds and 70 percent of 3-year-olds were enrolled.

High-quality early childhood education is very expensive, but former Federal Reserve Bank economist Art Rolnick estimates that for every public dollar invested, $10 returns to the economy. Kindergartners who show up ready have an 82 percent chance of mastering basic skills by age 11, versus 45 percent for those not prepared, and are 14 percent more likely to graduate from high school, according to the nonprofit First Five Years Fund, which conducts research on best practices in early ed. They are less likely to repeat a grade or be identified as needing special education services.

Harvard economists tracking the pandemic recession have found that, controlling for a child’s circumstances, having an above-average kindergarten teacher generates an additional $320,000 in earnings over a student’s lifetime. Indeed by an adult’s mid-20s, there is a clear relationship between kindergarten and college attendance, retirement savings, home ownership and mobility.

“Next year, kids are going to show up with wildly divergent needs.” —Chelsea Coffin, D.C. Policy Center

(Data on the effectiveness of D.C.’s near-universal pre-K are hard to come by. In March, the city auditor said education officials are not adequately collecting key data under a nearly 15-year-old mandate to track student outcomes. Since the program’s creation, District of Columbia schools overall have shown nation-leading progress on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the so-called nation’s report card, but a number of factors could be at play.)

Mustafa started out in the 3-year-old program at the Parklands@THEARC campus of AppleTree Schools, a much-lauded D.C. network of public charter preschools. Walker had wanted to send Mustafa to Martha’s Table, an early education center closer to home that also offers health care, clothing, employment assistance and other services for neighborhood families, but there were never seats when she called. A couple of weeks before the pandemic arrived, space opened up.

The school provided Walker with a tablet, but Mustafa’s participation was spotty. At home, the internet didn’t work reliably, and when it did, it didn’t always line up with the 30-minute Zoom windows for class. But the boy’s teacher gave Walker explicit instructions on everything from getting online to making sure he understood lessons.

“I asked for the same work they do at school,” Walker says. “I’m adjusted now, but in the beginning it was hard.”

In Washington, the steepest enrollment declines appear to be in schools with concentrations of children considered at risk, says Chelsea Coffin, director of the D.C. Policy Center’s Education Policy Initiative. Focus groups on pandemic schooling her organization has held with parents and teachers suggest that families that lack good technology are prioritizing keeping older kids — who don’t require constant prompting to sit still — caught up. Younger students, like Mustafa’s potential classmates, fall by the wayside.

“Maybe kids are sitting down for half an hour a day, and that’s a big win for parents,” says Coffin. “Next year, kids are going to show up with wildly divergent needs.”

Educators are aware of the size of the problem, says Coffin, but for months were too overwhelmed trying to navigate school closures and physical safety to begin planning for next year’s kindergarten crisis. “I don’t think schools have the bandwidth right now,” she says. “There’s just a lot of oxygen being taken up by reopening debates.”

‘Teacher, administrator, short-order cook’

Distance learning has been a trial for Jennifer Turner, a single mother of four, ages 13, 9, 5 and 3.

“I’m a teacher, an administrator, a short-order cook,” she says. “The last year was definitely a challenge for me.”

A 911 dispatcher, her normal shift is 6 p.m. to 6 a.m., which used to give her time to get home, make breakfast and get the children dropped off at the different schools D.C.’s enrollment lottery had assigned them. Then she would sleep.

School shutdowns changed all that. The first few months, Turner relied on catnaps to try to stay alert night and day. In September, she got two lucky breaks. A spot opened up for her son, Zailyn Morsell, in a pre-K classroom for 4-year-olds at the school where her fourth-grader, Javen Hutchins, is enrolled, cutting down on her daily drive time.

Then, she realized that she didn’t have to contract COVID-19 to take advantage of the city’s leave program. She was eligible for 80 hours of paid time off just for being impacted by the pandemic. Turner took her leave in four-hour chunks, allowing her to stop work at 2 a.m. and get a solid four or five hours of sleep before she had to start overseeing distance learning.

Getting Zailyn to participate in virtual preschool was a struggle. “He was very reluctant to get on the computer,” she says. “He felt since he was home he shouldn’t have to do school.”

With the boy focusing in 15- and 20-minute increments, Turner worried that he wouldn’t be ready for kindergarten. She bought dry erase boards, puzzles and workbooks so he could trace letters.

“The burden for all of this is really on the parents,” she says. “It’s up to you to make sure your kid is reading enough. It’s up to you to make sure they’re practicing enough. The struggle is real.”

Last year, stranded without day care or preschool, lots of parents couldn’t piece things together the way Turner did. In 2020, three times as many families as in a typical year did not enroll their kindergarten-age children, according to Urban Institute researchers. Nationwide, the children held back in the 2020-21 school year are also poorer and more likely to be of color than in years past.

Twenty-three percent of Hispanic kindergartners deferred enrollment, as did 14 percent of Asians, 13 percent of Blacks and 18 percent of whites. Contrast this with 2010, the most recent year for which data are available, when 7 percent of kids who put off enrolling were white and 3 percent Black.

Writing on the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s “Flypaper” blog, Michael Petrilli calculates that on a national level, some 8 million 4- and 5-year-olds will enter kindergarten next year with academic and behavioral needs that, left unmet, could persist throughout their academic careers. And because classes will contain children of different ages who missed the 2020-21 school year, the challenges this will pose will persist for years, he and other experts say.

“Just being honest, there’s going to be a whole set of experiments that are taking place,” says Jack McCarthy, president and CEO of the AppleTree Institute for Education Innovation and the associated network of preschools where Mustafa Fletcher originally enrolled. “We’ve not been through anything like this before.”

The number who are unprepared likely has mushroomed and will stay high for several years. Teachers will be expected to address an unprecedented array of unmet needs, which may take multiple school years to meet. The timeline could stretch on even longer if the missing students — or their teachers — don’t show up for the 2021-22 school year.

With the first day of school just weeks away, McCarthy says AppleTree has re-enrolled just two-thirds of its preschoolers and is unsure how many staff will be back. Vaccination rates in Ward 8 have trailed the rest of the city, while problems with access to child care and employment continue.

“I think it is going to be hard to understand who enrolled and who is planning to teach until early in the fall, which is not at all optimal,” says McCarthy. “Normally, by this time we would be fully enrolled with waiting lists and have teachers introducing themselves to parents and establishing relationships for the coming year, and all of that stuff is way behind.”

Grappling with a raft of challenges

Early childhood education in normal times includes heavy doses of the social skills that students will need to succeed in school, ranging from turn-taking and sharing to following instructions and transitioning from one activity to another. But many children who show up for pre-K and kindergarten next year will have spent a year or more essentially in a bubble, says McCarthy.

While their experiences at home will have varied widely, many of these young learners will have had little exposure to other kids or adults outside their immediate families, whose pandemic norms may well have included scary aspects of keeping COVID-19 at bay. “Fear of bad things happening,” he says. “That’s why we have to stay inside. That’s why we can’t go to the park. That’s why we have to keep our mask on. That’s why we have to wash our hands all the time. I have to think that’s going to have some effect on [the] socialization of these young children.”

One goal as AppleTree welcomes back families, then, will be creating a “positive narrative of success” about reopening that acknowledges that families’ degrees of comfort with in-person learning and vaccine rollout will vary. At the same time, teachers will gain a better understanding of how mental health issues may have affected each child.

A key thing AppleTree preschools hope to do is to shift from an age-based progression to one based on skills mastery. While some parents may want their child to enroll in the same grade as their same-age peers, McCarthy says, others may see the value in making sure preschoolers are truly ready for kindergarten, so missing skills don’t translate to learning gaps as the kids move up.

“If you can prevent learning difficulties with a higher degree of success, it pays off throughout the K-12 experience and on into adulthood,” he says. “I think it makes a lot more sense to focus on mastery, particularly in these early years, so that we can avoid all of the bad things that happen when kids aren’t prepared to do well in kindergarten and primary grades.”

“That range of experiences [in the classroom] is wider than it has been in generations, maybe ever, given the effects of a pandemic.” —Erica Greenberg, Urban Institute

McCarthy hopes D.C.’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education will allow children to remain in preschool until they acquire key skills — something he says the officials seem open to. To that end, AppleTree staff have been encouraging parents to consider keeping their children in preschool for more time, but again, the conversation has been made much more difficult by continued reluctance to return to in-person schooling.

Moving away from an automatic grade-level-a-year progression will likely be easier at the six AppleTree preschools than at schools that don’t have a formal relationship with the early childhood organization. AppleTree’s preschools are operated in conjunction with public charter schools, which already take personalized approaches to helping students hit developmental and academic milestones. In the case of children who enter the city’s kindergarten lottery and end up in a district-run or unaffiliated charter school, AppleTree preschool teachers will try to supply copious information about each child’s development, although, McCarthy says, “The handoff might not be as effective.”

A senior research associate at the Urban Institute, Erica Greenberg agrees that schools should consider flexible age groupings. To prepare children with different early experiences, kindergarten teachers typically rely heavily on a strategy educators call differentiation, modifying instruction or materials for pupils at different levels, she says.

“Now, this year, that range of experiences is wider than it has been in generations, maybe ever, given the effects of a pandemic,” Greenberg says. In addition to adapting activities and lessons, she suggests schools adopt trauma-informed approaches and consider that race has likely played a large role in a family’s experience of COVID-19. It’s important, she adds, for “parents not to feel like they are solely responsible for mitigating the impacts of the pandemic, both health-wise and economy-wise.”

Fordham’s Petrilli goes a step further in reconsidering normal grade-level progression, suggesting schools add a “grade 2.5” for this year’s kindergarten class and next year’s, spreading out over four years the academics and socialization normally taught in grades K-2. This could be accomplished by slowing down kindergarten and first grade in 2021-22, first and second grades in 2022-23 and grades 2 and 2.5 the year after, to allow teachers to cover all the early grades’ foundational material.

‘The reset is going to take a lot longer’

For people who live in D.C.’s prosperous neighborhoods, the recession may basically be over — if it was ever really felt. But for its poorest residents, there are dominoes yet to fall. One data point on the economists’ maps has generated intense speculation: Net small-business revenue in the zip code where Anacostia is located, 20020, rose 175 percent between the pandemic’s start and May 22, 2020. There are theories about this, but no certainty.

Extra federal unemployment benefits could have fueled higher spending by Walker’s neighbors. Much of the commerce in Wards 7 and 8 consists of mom-and-pop convenience stores, pharmacies and other small businesses selling essentials. Stuck at home, people could just have been consuming more.

Census records show that in the zip codes that are home to the lowest-earning 25 percent of District residents, the number of households using credit cards or loans to meet basic needs rose 17 percent in the first few months of the pandemic.

“This increased credit card spending among lower-income households does not necessarily mean that they are spending more,” suggested a report produced by the D.C. Policy Center for the local chamber of commerce. “They could be relying on credit to meet household needs and pushing the payments into the future when economic conditions improve.”

Whatever the answer, it wasn’t a sudden wave of prosperity. In the early weeks of the pandemic, one in five residents of Wards 7 and 8 anticipated not being able to afford their homes. By July 21, 2020, 23 percent of D.C. households overall said they had missed their last rent or mortgage payment.

This so-called chain reaction of material hardship compounds stressors on parents, in turn worsening conditions for children, notes Greenberg. “Families are now week-to-week, month-to-month making decisions about trade-offs. ‘Should I pay rent, or should I pay utilities? Should I pay rent or should I pay for food?’” she says. “Some of those decisions are conditioned by policy. When there are rent and eviction moratoriums, families feel like, ‘Okay, maybe I can prioritize food for this week,’ but then there’s always that fear that the bill will come due.”

The bottom line, says McCarthy, is that people should let go of the notion that the beginning of the coming school year, with its kindergarten class like no other, represents a fresh start. Students and teachers may continue to show up throughout the fall — or not — as unemployment benefits run out, COVID case counts and vaccine rates shift or according to a host of other factors.

“The reset is going to take a lot longer and involve a lot more data analysis than anyone thought,” he says. “People will watch and see what happens.”

Because students may continue to trickle into kindergartens and preschools through the fall and into winter, McCarthy says the flexibility with staffing, budgeting and other major elements of schools’ ability to serve a continually shifting student body that the mayor and other city and education officials are discussing is paramount.

For her part, Walker has a plan to revive her housecleaning business. She has earned a private COVID disinfection and safety certification and had business cards printed up with a new business name inspired by her kids: Two Boyzz in a Buckit. She’s taking the cards to local barbershops, hair salons and laundromats.

“Everybody’s going to want their home clean at this point,” she observes.

Turner’s leave ran out around the holidays. With schools slated to reopen to a small number of students at the start of February, she had a third stroke of luck: Zailyn and her fourth-grader won the lottery for in-person seats at Hyde Addison, their D.C. Public School.

With Zailyn back in school, Turner’s juggling act got a little easier. She can oversee 3-year-old Jax Morsell’s preschool, napping when the girl does or when her teenager, still at home, can spell her.

At her first parent-teacher conference a month later, Turner got to exhale a little more. In distance learning, Zailyn’s teacher had concerns about him. He didn’t participate much and, as with all her students, she was unsure whether he was getting too much family help in coming up with the right answers when he did join the class. Once back in the classroom, however, the teacher’s concerns evaporated.

In March, Walker learned that Mustafa had been accepted into a private, parochial school located in the same building as Appletree Ark. He will start kindergarten at Bishop John T. Walker School For Boys, which asks all its families to apply for the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, the first federally funded school voucher program in the country. The school will provide a private scholarship for any remaining tuition.

Mustafa had to interview in person to be admitted, making Walker anxious. After all the dropped Zooms and truncated activities, maybe he wouldn’t be ready for kindergarten after all. “I was so nervous,” she says. “But he aced it.”

This article is part of a series examining COVID’s K-shaped recession and what it means for America’s schools. Read the full series here.

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide financial support to Opportunity Insights and The 74.

Lead images: Getty Images

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter