Community Health Workers Can Play a Key Role in Keeping Families Healthy

A report calls for the integration of community health workers into early childhood well-child care.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The well-child visit is standard pediatric practice for the first three years of life. Every few months, parents or caregivers bring their little ones to the doctor to make sure they are growing and thriving. Because, for many families, these are the only encounters with a trained professional during this critical period, the value of well-child visits goes beyond the medical, connecting families to a wide range of supports for healthy development.

But time is tight. Compelled to get through all of the day’s appointments, doctors and nurse practitioners have about 20 minutes to check the physical side of things, but in the rush, questions often go unasked and unanswered.

That’s where community health workers (CHWs) come in. The job varies, and so does the title, but broadly, a CHW is a trusted connector and advocate who supports well-being in their community. Some work for a health care system or clinic, while others work for a school or nonprofit organization. The tools of their trade are cultural competency, a willingness to listen and a knack for building strong relationships.

A report published in 2024 by a group at the Pediatric Academic Societies calls for the integration of CHWs in early childhood well-child care. According to the report, these workers “often live in the community they serve, bringing unique and valuable skills to address health disparities. Their roles include providing culturally appropriate health education, coaching, social support, and direct services, as well as care coordination, case management, and care navigation, among others.” The authors also highlight that “community health worker” is an umbrella term that includes a range of roles including “health advocates, patient navigators, health coaches, and in Spanish ‘promotoras’ or ‘promotores de salud.’”

The report shows that an increasing number of hospitals and practices are integrating these workers into well-child care, highlighting evidence that this practice supports young children and families in low-income communities and sharing action steps for pushing this practice forward.

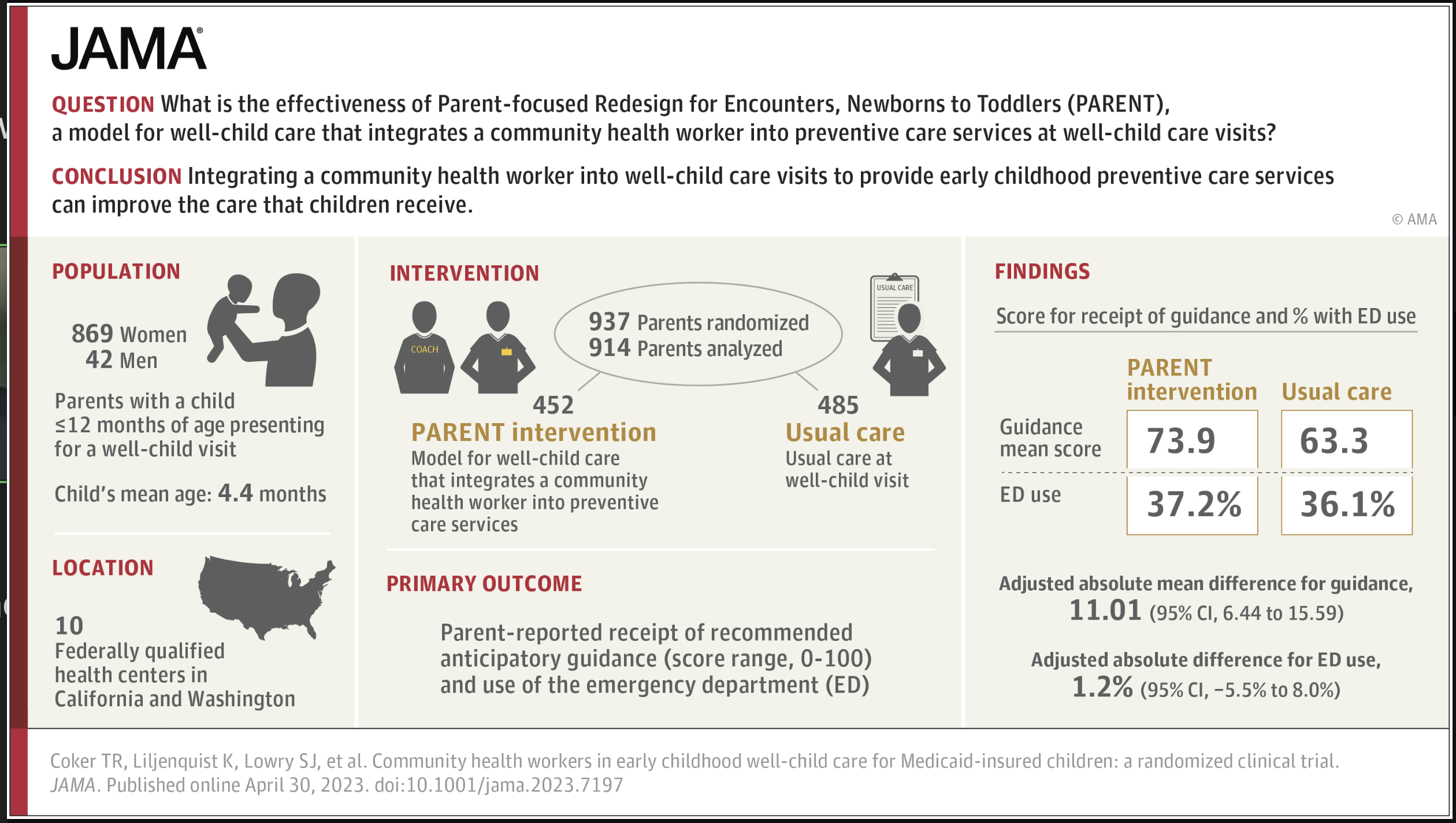

“If we don’t use this opportunity, then we’re going to pay later,” says the report’s lead author Dr. Tumaini Rucker Coker, chief of general pediatrics and professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Seattle Children’s. She points to a growing body of evidence on the value of community health workers. Coker worked on one randomized controlled trial of 914 parents, for example, that demonstrated the effectiveness for improving the receipt of preventive care services for families.

Another study she led, involving 251 parents, points to greater participation in well-child appointments and reduced emergency room visits — which translates into cost savings.

“Families need to talk with someone about the challenges that they’re facing in parenting,” says Coker. “They might need advice on doing that hard work of parenting. They might need emotional support, but they don’t always want to tell their primary care provider all the struggles that they have, other than ‘My kid has a rash or cold, those kinds of things.’”

“We tend to look busy,” she admits.

Community health workers offer support on many other issues that come up related to areas including parenting, eating, sleeping and cognitive development. They can identify developmental delays to help ensure that young children arrive in kindergarten ready to learn. They can connect families to services such as supportive housing. It depends, she says, on the character and capacity of the community.

The CHW role first came into prominence in the 1990s and was related to the treatment of children with asthma, as medical providers realized that having someone evaluate environmental factors in the home could help manage the condition. The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrated the part community health workers play in keeping families healthy, as they expanded bandwidth to support families as medical offices and hospitals were stretched to capacity. As Coker recalls, “It was like, Wow, families really need this. The needs really outstripped the capacity that clinics had.”

There’s an ecosystem of national and local organizations and networks focused on community health workers. The Healthy Steps Network, for example, integrates specialists into pediatric primary care teams. These specialists are highly trained and are expected to be conversant in professional practice guidelines, regulations, and laws; to possess a basic vocabulary in medical terminology and relevant diagnoses; and to know about health screens, medical procedures, and referral processes. Meanwhile a pilot program in New Haven, Connecticut combines birth doula training with community health worker instruction.

While training is key for these professionals, Coker contends that the effectiveness of CHWs is not necessarily tied to a specific degree, license or certificate, making the role even more cost-effective than originally envisioned. “If we require a level of training and education that’s too high,” she says, “then it becomes impractical for many communities. It’s not about a license. It’s about that ability to connect with people in the community in a way that builds trust.”

With team-based pediatric care — a model that fosters collaboration across medical practitioners and community partners — she says, the goal is for “everyone to be working to the top of their ability and the top of their training.”

Even if a community health program is low cost and ultimately saves money for the family and the nation, it’s still an investment. Community health workers are paid through a range of funding mechanisms, and these days, Medicaid — a key source of funding — is in jeopardy.

Coker explains that while CHWs are increasingly funded through Medicaid, multiple states have amendments that should cover the work even in the event of diminished federal dollars. She says the current situation might compel policymakers to say, “Hey, let’s be more efficient with the use of our primary care providers, our nurse practitioners, our docs who are more highly specialized than a community health worker.”

Medicaid, she says, has been instrumental in supporting team-based care and community health workers, adding, “And I just hope we don’t go backwards on that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)