Collins: To Better Support the Nation’s Transgender and Nonbinary Students, Nonbinary Educators Must Have a Seat at the Policy Table

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

“You all know that I have been out as a lesbian for a long time,” the high school junior said on a stage in front of 300 other girls and gender-diverse students. As a faculty member, I watched as a huge cheer erupted across the auditorium. “And now I’m here to say something else. I’m nonbinary.” An even louder cheer rang out. I marveled to see the acceptance and support from the student body, considering how challenging my own journey as a nonbinary person had been. Here in middle America in 2019, these students showed me something I didn’t think possible when I was a kid: immediate acceptance and love of a peer, regardless of gender.

“Nonbinary”-gendered students are just that: students whose genders don’t fit in a binary. They are neither female nor male. This isn’t about anatomy. It’s about gender, or how these students see themselves when they look in the mirror each morning. Some of my former students had no gender at all (agender), while others had very strong gender identities. Some students lean feminine (femme), others lean masculine (masc), others lean a different way (third gender) and others fluctuate. “Nonbinary” isn’t a single, monolithic group, but an umbrella term for those of us who don’t fit into a society made up of only “pink dresses” and “blue baseball caps.”

There are no good statistics on the number of nonbinary students in the United States. The majority of those I have met are closeted in some way (from friends, family, school or a combination), and that makes reliably counting these students a shifting and near-impossible task. When they do come forward, they often know that they are inviting trauma into their lives. Not everyone will be as kind as the people in that auditorium. In fact, most people may not be — and virtually all transgender and nonbinary students are at risk of increased bullying, physical assault and mental illness due to that pervasive lack of acceptance.

As a nonbinary teacher who came out in my 30s, I paralleled this process, but from a far different perspective. When parents or teachers misgendered me, I had the ability and authority to correct them. When I noticed that an area of the school did not have a unisex bathroom (many nonbinary individuals prefer unisex bathrooms), I had the ability and authority to speak with the administration. When I felt it was time for my name to more accurately represent who I am, I had the ability to make that change and to ensure that my email address, school accounts and school ID were updated along with it.

Most nonbinary students have none of that situational authority; they must simply suffer through. To a cisgender person (someone whose gender matches the gender that they were assigned at birth by a doctor), some of these concerns might seem trivial. Can’t you just use any bathroom? What does it matter that the school website lists your old legal name? Such people don’t — and maybe can’t — understand the trauma and anxiety that nonbinary persons go through as we navigate the near-constant gendering (and misgendering) that takes place in highly formal spaces such as schools. School dances that are fun, identity-forming events for so many students become panic-inducing ordeals for others. Constant code-switching as we swap out names during the day based on a teacher or peer’s willingness to understand our gender can lead to persistent states of anxiety. Dread of binary bathroom and locker room choices can lead to depression and absenteeism. Every day becomes a series of compromises between our safety and our identity. It is a fragmented life that many cisgender and some binary transgender individuals do not have to endure.

This fragmentation of students’ lives begins at the top. When I worked at the U.S. Department of Education under Secretary Betsy DeVos during the Trump administration, I was asked to present at an upcoming “Fathers and Family” event in celebration of Father’s Day. I was openly pansexual at the time but closeted about my nonbinary gender. I was selected because I was a father and led the department’s work on early learning and educational technology. Soon after the invitation, I found out that I would be sharing the department’s auditorium and stage with the Family Research Council — an anti-LGBTQ+ group in favor of conversion therapy for people like me.

I was faced with a conundrum, as so many federal workers were during the Trump administration. Do I step aside and let someone else speak hate? Or do I fragment myself more but speak truth to power? I spoke of parents. I spoke of love. I spoke of spending more moments with our children. And I received a standing ovation from the assembled crowd of Washington, D.C., policymakers, aides, professors, think tank professionals and bigots. It was a moment that broke me, and I was thankful to quit my job leading educational technology policy in the government soon after.

While some champions for LGBTQ+ student rights remained in the secretary’s office after I left, other LGBTQ+ federal employees like myself were increasingly pushed out across the executive branch. If not directly, then through hostile and petty work environments, through increased partnerships and work with openly transphobic and homophobic organizations and individuals, and through myriad other workplace shifts away from the Obama administration’s days. In the loss of these voices, policies discriminating against transgender and nonbinary students continued to grow. These vulnerable students need greater support to undo the inequities of the past four years.

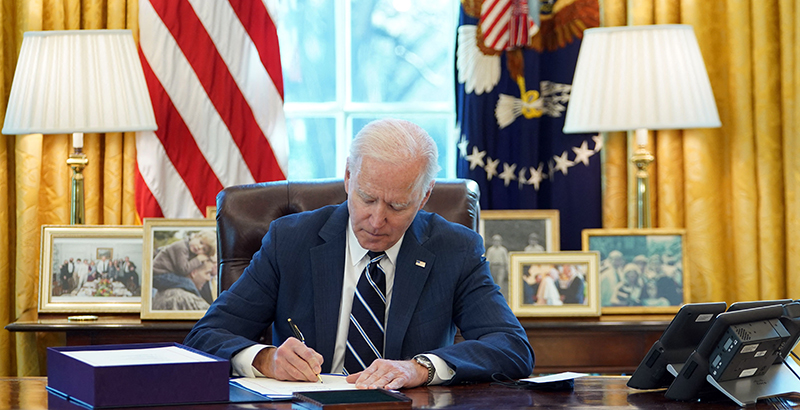

President Joe Biden’s selection of Rachel Levine shakes history. As assistant secretary of health, she is the first transgender person ever appointed to a Senate-confirmed position. She will give voice and representation to so many of us transgender individuals who struggle with, and have been actively pushed out of, medical care. As wonderful as it is to see a transgender woman in a top health post and to see the Biden administration begin to roll back entrenched discrimination against transgender students, my former high school students in Cleveland and students everywhere need an advocate and representation in education.

No openly nonbinary person has ever held a position of power in the White House or at the U.S. Department of Education. We have been confined to schools where, until just last year , many of us could be fired simply for wearing nail polish or a tie. Those of us who have made it higher up in policymaking circles have been forced to hide our identities for fear of reprisals.

It’s time now. Nonbinary students across the nation have been taking that terrifying step forward to demand the right to be recognized as who they actually are. They deserve representation at the highest levels of policymaking as well. They deserve to have people who are just as out of step with binary genders as they are sitting at the table and helping to craft the decisions that will impact them and the students who come after them. As policymakers, as political appointees and as career professionals. The excuse that there is no one to fill those positions is no longer tenable. You can find classrooms from coast to coast where teachers are referred to as Mx. It is time to lift them up and to include them in the policy conversations shaping the future of our nation’s children.

Grace Collins served as the Department of Education’s educational technology liaison under Secretaries of Education Arne Duncan, John King and Betsy DeVos. Grace currently runs a startup focused on games, education and equity.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)