Instinctively, Chris chose charter schools as his goal, which made sense. He was looking to make a big difference where it was needed most. He grew up poor, joining the Army right out of high school. He got some breaks along the way, and he wanted other poor kids to find those same breaks. You don’t make that kind of difference teaching in our upper-income neighborhood of Arlington. To find something akin to plucking swamped sailors from the ocean, you go to places like Newark.

In the long run, Chris wanted to run a charter school, which fit his management skills (after leaving flying, he managed Coast Guard education programs, and already had a K-12 teaching certificate). But he knew he had to teach first. How could you possibly manage teachers at a culture-intense charter school unless you knew, brick by brick, how that unique classroom culture got built?

I watched with both awe and trepidation as he pursued a really tough choice. Joining TFA meant bunking and training with recent college graduates who probably wouldn’t know what to make of this tightly muscled guy with the shaved head and booming voice. It meant his new boss would be half his age. It meant countless, unpredictable changes in his life. It wouldn’t be an easy journey.

But even I was surprised by some of the bumps along his path. My favorite story: When Chris announced his intentions to pursue TFA and work at a Newark charter school, the parents at his daughter’s upscale Virginia elementary school smiled, politely nodded and wished him luck. Clearly, many thought he was out of his mind. In this neighborhood bustling with lawyers, entrepreneurs and upper-level government workers, being a chopper pilot is unusual but kind of intriguing. Teaching in Newark…not so much. Aren’t you imperiling your wife and daughter?

But the reaction to Chris’s decision couldn’t have been more different from his fellow pilots. They thought it was cool, way cool. They got it. Not much different from the kind of risk-taking they signed up for as search and rescue pilots. They made Chris swear to stay in touch so they could see how it all turned out. “In the Coast Guard, you’re proud of the fact you have chosen a career path dedicated to the service of others. You’re willing to sacrifice yourself for whatever cause it is. It’s that kind of mentality,” Chris said. “These people got it.”

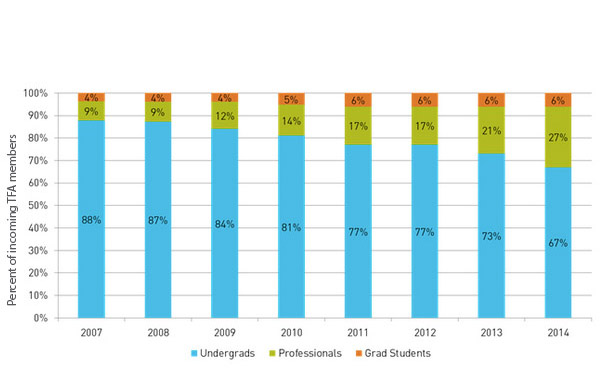

Actually, it worked reasonably well. The key was in choosing the right people. Not only was TFA getting top college graduates, but they chose only 19 percent of the applicants, and it showed. “It’s not that TFA are good magicians or anything. They’re just real good at selecting people,” Chris said. “I could take the same group of people and dedicate them to something else and they’d be just as good, right?”

The social interactions were, well, a little less smooth. A rabid Seinfeld fan who can quote entire show sequences, Chris got nowhere telling Seinfeld jokes with this group of 22-year-olds. Maybe they had seen some reruns; maybe not. Fortunately, Chris’s roommates were other career changers. No coincidence there. Chris and his roommates, both Wall Streeters looking for more meaningful second careers, kept steady hours – early to bed, early to rise. Unlike the other corps members, who were just a few months out of college and had never held steady jobs before. For them, it was college all over again, sharing music and gossip in the hallways, staying out late at karaoke bars. Other than everyone joining TFA, they didn’t have much in common.

Many of the young corps members made it clear they were there for two years of service before moving onto something else. “We respected them for who they were and what they were doing,” said Chris. “They are some smart kids. Some want to be doctors, and they will. Some want to be politicians and lawyers, and they will. They are going to be the people our society holds as being successful, accomplished people, so good for them for taking this on, to make $40,000 and $50,000 doing this before moving on.”

For Chris, the hardest part was adjusting to what he dubs “rainbows and unicorns” sessions, where corps member share, emote, tell “life river” stories about themselves and work long and hard on cultural awareness issues, especially involving race. Chris got it. He knew he was headed into a classroom where every single student was likely to be poor and African American. And here he was, white, male, shaved head and military. He understood the reasons for the rainbows and unicorns, but it didn’t come naturally. There’s no touchy feely talk in the military. “Over time, the hugs and kisses wear you out. I don’t need to share my innermost thoughts.” But he got through it.

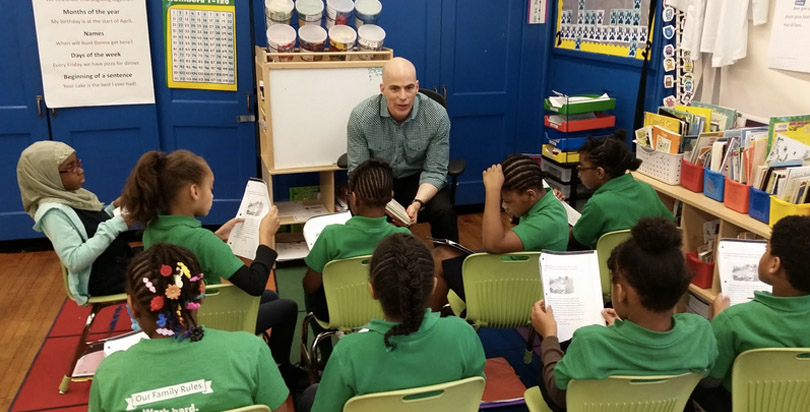

Fortunately, Chris’s principal, Lindsay Schambach, had anticipated all this and assigned him to a lead teacher, Diane Revalski, who is both a crack educator and someone unlikely to be intimidated by Chris. On the April day I visited the classroom, every so often Diane would climb on a desk, with a #2 pencil thrust through her tight bun, and loudly announce new orders for rotating learning groups. She was a perfect match for Chris, who by this point in the school year was teaching with confidence. His pacing, going through small group reading sessions, seemed flawless. The respect among the kids was evident.

What happened to turn it around for Chris? Everyone has a theory. For Lindsay, the turning point came when Chris truly bought into school culture, the rainbows and unicorns, if you will. Most memorable was the time Chris plunged into the weekly competition among the classes to come up with the best chant. Chris taught them a military-style marching/running Jody chant. (In the military Jody is the pretend name of the person who steals your girlfriend when you’re away) Chris added KIPP language, and the chant stuck:

You scholars

Better do your best

Or you find yourself

Left with all the rest

Love it, learn it…

“The kids loved it,” said Chris, “and it became this big thing in the school. ‘Ohhh, Mr. Bonner is showing a little bit of himself and it’s unique.’”

On school spirit day, he came dressed in a tuxedo. And then there was the time, during a Western theme day, that he came dressed in chaps, a vest, handkerchief and cowboy hat. All those were important transitions, said Lindsay, from getting kids to do things because you outrank them to getting them to do it because they love you. The latter works way better. “Early on, Chris had an over-reliance on the rules without realizing that relationships are what make a school’s culture every day.”

Caryn Bonner has her own sense of when the corner got turned. It was a December weekend when her husband first referred to his students as “my” kids. For Chris, the turning moment was unexpected, the day he arrived back in the classroom after the holiday break. He had expected a tough day re-immersing all the students in the fast-paced KIPP academic world. “I was expecting a nightmare,” he said, “that they would have forgotten everything and we would be starting over from square one. But that didn’t happen. I came back, and the kids missed me, and I missed them.”

As for the plan to become a principal, like Lindsay Schambach, that also changed. “I can’t work 15 hours a day like Lindsay does,” he said. “Somebody has to get [our daughter] and get dinner on the table.”

From Lindsay’s perspective, Chris ran into the five-minutes-free phenomenon. In the military, he could always find five minutes of free time. “Here, you have five minutes free and realize you can make copies, go to the bathroom and make three parent calls.” Lindsay recalls Chris telling her, “I was part of one of the most efficient organizations, the military, and I have never had to maximize my time like I do now. Every second counts here.”

What would work, and be a better fit for Chris, would be taking on the school operations role. Essentially overseeing every aspect of the school that’s not instructional — budget, food service, custodial, supplies, buses, facilities — it would be a perfect job for someone with a military background. Lindsay agrees. Next year Chris will both teach and begin to take on those tasks as part of his training. As KIPP continues to expand in Newark, the opportunity to grow in a job like that is enticing. And his teaching experience will be invaluable. “It’s like being an enlisted person who becomes an officer. You know what it’s like to be the person being led, so you make decisions based on that experience.”

So what does Chris’s story say about TFA’s future? Yes, the situational awareness acquired as a helicopter pilot translated into classroom withitness. But what proved to be just as important was an embrace of the teaching culture, unicorns and all. Everyone agrees Chris became an effective teacher in less than a year. How many first-year teachers can claim that?

The second question: Can TFA and KIPP count on career changers? They already are, with general success. But the massive time commitments required of managers may keep many of them, especially those with family duties, from moving into top leadership roles. Finding the right talent to fill that incredibly demanding job will continue to be a challenge — a challenge that threatens to limit the growth of elite charters.

Emerson Collective fellow Richard Whitmire is the author of several education books, including 2014’s On the Rocketship: How Top Charter Schools Are Pushing the Envelope.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)