Closing Bad NYC Schools Helped Next Generation of Students: 5 Takeaways from Groundbreaking Report

When school closures swept New York City under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Chancellor Joel Klein, what some saw as the key to turning around “dropout factories,” others decried as an attack on public education, teachers, and disadvantaged students.

But a new study from NYU’s Research Alliance for New York City Schools presents evidence that between 2002 and 2008, the city’s strategy of phasing out low-performing high schools led to meaningful improvements for students who would have otherwise attended those schools.

Furthermore, students who attended schools during the phase-out process were not visibly harmed (or helped) by the process.

The research — the first of its kind to study New York City high school closures — is sure to be seen as a vindication of the controversial closure strategy employed under Klein and Bloomberg. In contrast Mayor de Blasio has criticized the practice as failing to solve the problems of struggling schools and generally emphasized a “community schools” model as an alternative.

Because of the study’s limitations, however, the long-term policy implications are unclear.

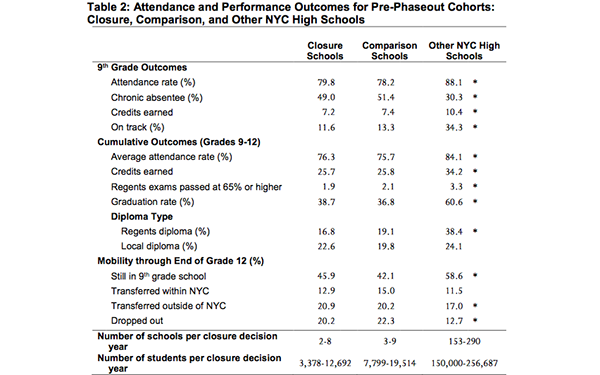

The report identified 29 high schools that were ultimately closed, finding that these schools had low graduation and attendance rates, even after accounting for differences in student backgrounds. But many schools — referred to in the report as “comparison schools” — that were similarly low-performing were not phased out. This key fact is what allowed researchers to measure the impact of school closures: by comparing students who went to comparison schools with those who attended, or would have attended, phased-out schools.

(For bigger charts see original NYU Steinhardt report)

Five key findings from the new NYC school closure research:

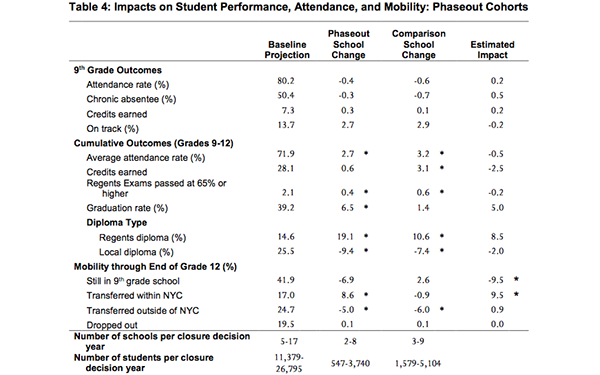

1. Students attending “phase out” schools were not harmed — or helped — by the process.

When the city first announced that certain high schools would be “phased out” over several years, many worried that the students remaining would be harmed, in part because schools with an expiration date could face a drop in morale or have a hard time recruiting effective teachers.

In fact, looking at a variety of indicators — attendance, chronic absenteeism, credit accumulation, and graduation rates — the report found no evidence to support this contention.

Interestingly, students who actually remained in the phased out school seemed to have a higher graduation rate than students attending similar schools that weren’t being phased out. Notably, both types of schools experienced large increases in graduation rates, but phased out schools’ gains were even larger.

However, the process of phasing out a school led to a significant increase the numbers of students who left the school, which is typically associated with a decline in graduation rates.

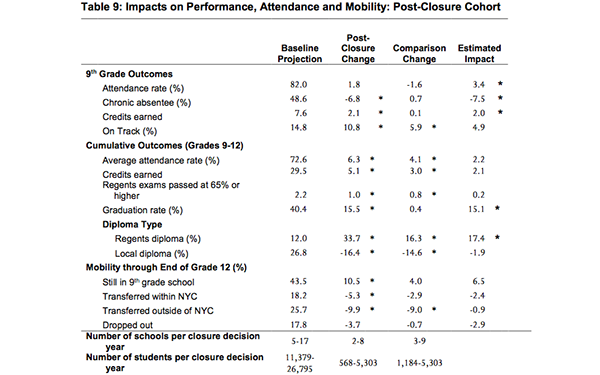

2. Students who were re-routed into different high schools were more likely to graduate.

The study showed that students who would have likely attended a phased out school — but didn’t because it was closed — benefited significantly.

On average, those students attended better schools and were much more likely to graduate high school, by about 15 percentage points. This increase was large, statistically significant, and came from the accrual of Regents diplomas as opposed to the state’s less rigorous “local” diploma.

3. These students may also have benefitted from better attendance and lower drop-out rates — but impacts weren’t necessarily statistically significant.

The report includes estimates of other impacts on students who found themselves routed to different high schools — impacts such as attendance, drop-out rates, and credits earned.

All such estimates suggested beneficial effects of school closures, but many of the impacts were not statistically significant, meaning the researchers couldn’t be sure they were the result of the closure policies.

4. It’s impossible to know what would have happened if schools were not closed.

The NYU researchers do a thorough and rigorous job comparing students affected by school phase outs with those who were not affected. Still, it is impossible to know what would have happened if the schools hadn’t been closed — or if another school improvement intervention had been used instead. Mayor de Blasio is currently employing a community schools model to turn around ineffective schools. How does that stack up against school closures? We simply can’t know at this point.

Moreover, the study only attempts to measure academic outcomes, meaning it may overlook other unintended consequences of the policy that did not show up in graduation rates. It’s an important caveat that’s acknowledged directly in the report: “Our study does not examine closures’ effects on educators, parents, and neighborhoods (or on aspects of students’ experiences not reflected in their attendance, mobility and academic outcomes.”

5. There were large gains made across the board in New York City schools, but the policy implications of this study are unclear.

Any reading of the NYU data indicates that students made significant gains between 2002 and 2008.

How significant? In some instances, the report doesn’t show a positive impact on phase outs per se because the two groups of schools — the phase-out group and the comparison group — were both showing significant improvements.

As the report concludes: “Recent studies provide rigorous evidence about the effectiveness of [New York City’s] constellation of reforms.”

Yet while studies like this can tell us what happened in the past, they can only be suggestive about what should happen in the future.

It’s worth noting that New York City schools have changed significantly since the early 2000s, when this research time frame begins, and policy decisions should reflect that. As the report cautions: “Dramatic actions like school closures may have set the system on a positive trajectory, but they may not be sufficient for the challenges of today and the future.”

(Disclosure: The Seventy Four is partially funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, and Howard Wolfson, head of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ education programs, serves on The Seventy Four’s Board of Directors. Co-founder Romy Drucker previously worked in the New York City Department of Education.)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)