What a long, strange trail it’s been.

Since The 74 launched in July 2015, we’ve aimed to make education front-page news, including extensive coverage of education in the presidential election. From our New Hampshire education summit to countless debates that came up short on K-12 talk, to a day on the campaign trail with high school volunteers in Maryland, to both the Republican and Democratic conventions, we’ve covered it all.

And now, in little more than a week, Americans will vote for a new president, one whose administration will be responsible for implementing the new, still-contentious Every Student Succeeds Act, working to enroll more young children in preschool, cutting down on college costs and expanding education options for American families.

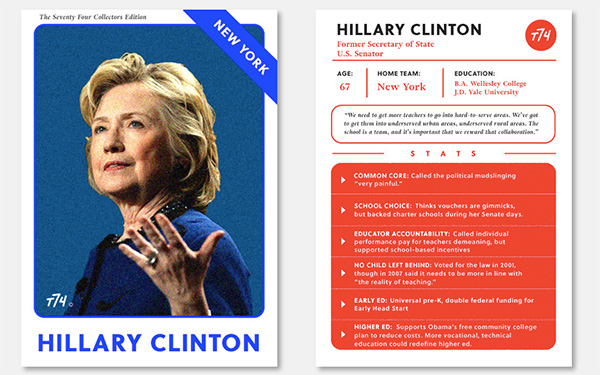

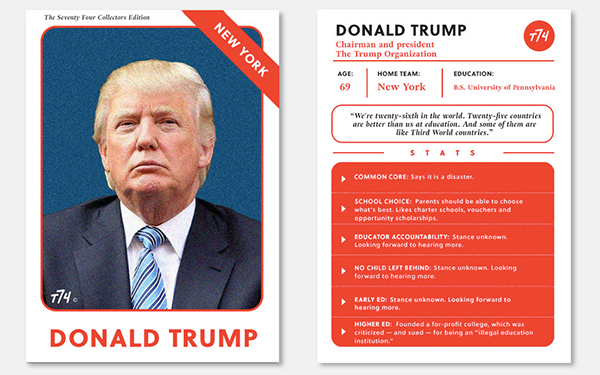

Although both candidates selected running mates with extensive K-12 education records, there is no contest at the top of the ticket. Hillary Clinton’s record stretches back to the 1970s, and she has released detailed policy proposals covering preschool, K-12 and higher education. Donald Trump, meanwhile, has made little imprint, relying on talking points and a “plan” that raises as many questions as it answers.

Without further ado, and for the final time, here are the education records of the 2016 presidential candidates.

Clinton: From the Children’s Defense Fund to free college

Clinton’s education advocacy began early. Before she entered public life upon husband Bill Clinton’s election as governor of Arkansas, Clinton worked with children’s advocate Marian Wright Edelman to expose school segregation in the South, getting the administrator of a local private school to admit it didn’t admit black children — a violation of its tax-exempt status.

She also worked with the Children’s Defense Fund, surveying students in New Bedford, Mass., about why they weren’t in school. Her work was combined with others across the country in a report that found that thousands of children with disabilities had been “treated as uneducable” and kept out of public school. The report’s 1974 publication fueled the push for the federal law, passed in 1975, that requires public schools to provide an appropriate education to children with disabilities, today known as the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act.

“It became clear to me that simply caring is not enough,” Clinton said during her acceptance speech at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia. “To drive real progress, you have to change both hearts and laws.”

While she was First Lady of Arkansas, Clinton worked on both preschool and K-12 education issues, pushing to bring an early-education program — Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters — to Arkansas and leading an education-reform commission that proposed new standards and a host of other changes in 1983.

“I called the legislature into session hoping to pass the standards, pass a pay raise for teachers and raise the sales tax to pay for it all,” Bill Clinton said at the Democrats’ convention. “I knew it would be hard to pass, but it got easier after Hillary testified before the education committee — and the chairman, a plainspoken farmer, said, ‘Looks to me like we elected the wrong Clinton.’ ”

Clinton’s running mate, Sen. Tim Kaine, was previously governor of Virginia, where he worked to expand early childhood education. In the Senate, he’s written bills focused on career and technical education. His wife, Anne Holton, who resigned as Virginia’s education secretary shortly after Kaine was picked, has carried the Democrats’ education message.

On the campaign trail this year, several of Clinton’s policy proposals have addressed early education, most notably her call for universal preschool for 4-year-olds.

“It’s time we realize once and for all that investing in our children is one of the best investments our country can make,” she said at a day care center in Manchester, N.H., in June 2015, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Since then, she has also announced plans to extend the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program to an additional 2 million young children. The program sends nurses and social workers on regular visits to pregnant women and new families to help with health-related issues, better prepare children for school and instill positive parenting practices. Clinton has also proposed increasing pay for child-care workers and boosting tax credits for low-income families.

Clinton’s most controversial education-related moment came during an interview with commentator Roland Martin last fall, when she stated that charters don’t enroll the “hardest-to-teach” students or, when they do, don’t keep them.

The remarks roiled education advocates: She was accused by charter supporters of flip-flopping to please teachers unions and praised by charter opponents for speaking out about how charters appear to succeed.

(The 74: Hillary Clinton Rushes to Clarify Charter Critique in Sit-Down with AFT and Data-Driven Blog Post)

(She would later praise successful charters during a National Education Association speech in July, eliciting boos during an otherwise warmly received performance.)

The Every Student Succeeds Act shifts much K-12 education policy previously under federal control back to the states, but Clinton praised the law for its support for preschool, “a better balance on testing” and new funds for charter schools.

She also released a detailed proposal designed to stanch the school-to-prison pipeline: a plan that would put an extra $2 billion into schools to reform overly punitive school discipline policies and support guidance counselors, school psychologists and social workers. Clinton said she would encourage the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights to intervene in states that don’t change their discipline practices.

“The bottom line is this: We need to be sending our kids to college. We need a cradle-to-college pipeline, not sending them into court and into prison,” she said.

(The 74: Clinton Doubles Down on Obama’s K-12 Agenda, Commits $2 Billion to Fight School-to-Prison Pipeline)

Other K-12 initiatives include a call for a national campaign to “modernize and elevate the profession of teaching,” expansion of computer science classes for all students and updating of school buildings.

Shortly before the end of the campaign, Clinton released a plan to funnel $500 million to states to develop anti-bullying strategies. The plan, and an accompanying campaign ad, were fueled by what the campaign says has been a rise in bullying, particularly of Muslim and immigrant students, in the wake of Trump’s incendiary claims.

On higher education, Clinton released a comprehensive plan that would make community college free, provide debt-free college for all and free tuition for students from families making under $125,000 a year, and add supports for historically black- and Hispanic-serving institutions.

Trump: From offending Bronx children to a half-plan

Donald Trump was educated in private schools and allegedly hit a teacher before being transferred to a military school, where he was considered competitive as both a student and an athlete and earned a reputation as a ladies’ man.

One of his first public education appearances, as principal-for-a-day at a poor elementary school in the Bronx nearly 20 years ago, was a PR disaster. He famously held a lottery to award free Nikes to only a few kids out of the large group of cheering students. One student asked why he wasn’t awarding scholarships instead.

“I’m not so sure that he — he didn’t understand, to give low-income kids a lottery for sneakers was an insult,” the principal later said.

Similarly, when he came across a bake sale held by the chess team to pay for travel expenses, Trump handed over a fake million-dollar bill. He ultimately donated $200.

“The thing that it really left me with was that this man had absolutely no clue about education,” said the chess coach.

From the start of the campaign, Trump has been staunchly opposed to the Common Core, in keeping with conservative dogma.

But as with many of his statements on other issues, his characterization of the standards has been exaggerated.

“Common Core is a total disaster. We can’t let it continue. We are rated 28th in the world … and frankly we spend far more per pupil than any other country in the world. … Third-world countries are ahead of us,” Trump said in a Facebook video.

He also charged in a primary debate that the standards effort has been taken over by the federal government — a big stretch. And his conflation of the standards with American students’ ranking against their international peers has been widely debunked.

Apart from his flawed criticism of the Common Core and a possible rise in bullying of immigrants and Muslims that advocates say he inspired, Trump largely left the education world scratching their heads about what he thought.

In August, a breakthrough seemed possible: The campaign announced that it would focus on education for a week. A probable pivot to charters and choice made sense as a way to help reach groups where Trump has been underwater, particularly black and Hispanic voters and reluctant members of his own party.

Trump unveiled a plan of sorts at a floundering charter school in Cleveland; as anticipated, it focused largely on school choice. Like everything else in Trump World, it included outsize promises and few details.

The plan hinged on moving $20 billion in federal funding to bolster school choice. The money would be given to states in block grants, according to the plan, and funding — about $1,800 for each of the 11 million children the campaign said were living in poverty — would follow them to public, private, charter or magnet schools.

“Our government spends more than enough money to easily pay for this initiative, with billions and billions of dollars to be left over,” Trump said.

But $1,800 is generally insufficient for private school, and Trump suggested that state politicians could chip in more to get to a number closer to the actual cost of tuition. He said he would press the issue as president.

“As your president, I will be the nation’s biggest cheerleader for school choice,” he said.

He also argued for merit pay and continued his sharp criticism of the Common Core.

GOP VP nominee Mike Pence, currently the governor of Indiana, was aligned with Trump in his opposition to the Common Core and promotion of school choice. Under Pence, the Hoosier State was the first to back out of the new standards; he praised Indiana’s robust charter sector and worked to expand the state’s voucher program.

In October, Trump unexpectedly spoke for six minutes on higher education during an unrelated speech, endorsing income-based student loan repayment options, and criticizing what he characterized as administrative bloat in colleges and their refusal to spend money from their endowments. He also pledged to protect students’ free speech rights, according to Inside Higher Ed.

Trump said his education agenda, which he called the “School Choice and Education Opportunity Act” — expanding choice, ending Common Core, improving vocational and technical education and making college more affordable — would be among his priorities during the first 100 days in office.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)