Cleveland’s Surprising College Trend: Despite Pandemic, Data Show City’s HS Seniors Bucking National Trends, Taking Steps Toward Higher Ed Ahead of Last Year’s Pace

Even as fewer high school students nationally make plans to attend college this fall because of the pandemic, Cleveland high school students are bucking the trend, taking early steps to continue their education.

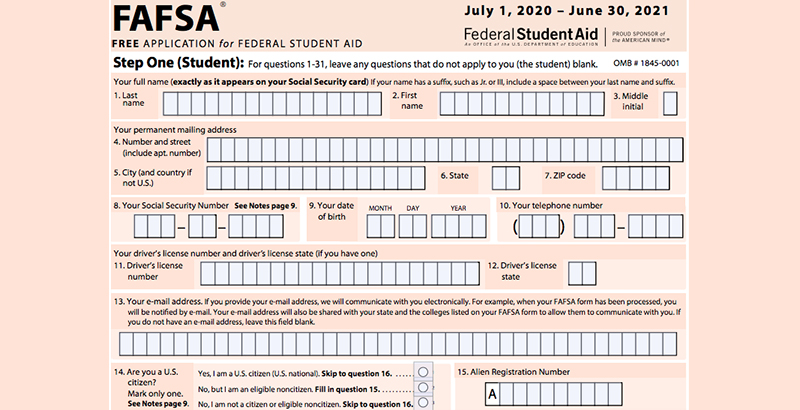

In a telling statistic, the percentage of Cleveland’s high school seniors that filled out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid has increased to 52 percent from 48 percent the same time last year. The rise comes while FAFSA completion nationwide has dropped 3.5 percent after schools were closed because of COVID-19.

Completing those forms is necessary to qualify for need-based financial aid at any college, and it is considered an early indicator of college enrollment. Cleveland leaders were worried they would see the same declines but are cautiously optimistic with district FAFSA applications rising.

“We know that there’s still room to go, but certainly in the context of the shutdown and quarantine and having students out of school the last two months, to have kids ahead of where we were last year on the critical indicators is good news,” said Jon Benedict, Cleveland’s spokesman for the Say Yes to Education college scholarship program that has been working to increase college enrollment in the city.

The upward trend, especially in a difficult time, has been years in the making.

Increasing college enrollment in Cleveland has been a major goal for several years, one that took a leap forward in January 2019, when the city, county, school district and several philanthropies raised nearly $100 million and launched a partnership with the Say Yes to Education college scholarship program.

Say Yes to Education, like other so-called “college promise” programs, commits to students a scholarship that covers tuition if they graduate high school and are accepted to college.

Whether Cleveland will beat the national trend won’t be known until the fall, when the National Student Clearinghouse releases its reports of college enrollment. Though FAFSA completion is up, other early indicators of college enrollment are mixed.

But Say Yes to Education brought first-ever gains to the city last year. After a few years of only 40 percent of Cleveland school district graduates enrolling in college, 44 percent enrolled last fall using the scholarships. That was an important step for a city where only 16 percent of adults have bachelor’s degrees, well below the 30 percent or more for the region, state and nation.

Cleveland families make a median $26,600 a year, according to census data, compared with the region’s median household income of $52,100 and national median of $57,600.

More than 200 communities in 41 states have college promise programs, in which districts, cities or private donors promise students scholarships to college if they graduate from high school, are accepted and enroll. Sometimes, these are limited just to the local community college, some are just for in-state public schools, and some, like Say Yes, also offer scholarships to private colleges that have agreed to partner with the program and share costs.

In most programs, like Say Yes, the scholarships are “last dollar” scholarships, covering the tuition remaining after other need-based aid like federal Pell Grants are used up. But students using the scholarships say they take away worries of affording tuition, reduce how much they have to work during college and let them graduate with little or no debt.

Michelle Miller-Adams, who researches promise programs for the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research in Kalamazoo, Michigan, home to the best-known program, The Kalamazoo Promise, said she hopes promise programs prevent declines in enrollment.

“We are very interested in the question of whether promise programs [including Say Yes] somehow protect students in their communities against the broader trends we’re seeing,” she said. “It’s very early — no one knows who is going to show up at colleges or universities in the fall, and a lot depends on what those institutions decide — but the falloff in FAFSA applications is a troubling trend.”

Miller-Adams said FAFSA completion in Kalamazoo is also avoiding declines, though representatives of the Kalamazoo Promise would not confirm that.

“I believe that promise programs can play an important role in signaling that college costs are manageable and also in providing hands-on support and messaging to students that will help keep them on the college-going path,” she added.

In Kalamazoo, she said, “Promise Pathways Coaches” in city high schools work constantly with students to keep them focused on what they need to attend college.

In Cleveland, a nonprofit organization called College Now Greater Cleveland handles college advising for the school district and has continued having its advisers call students constantly from home to keep them on track.

Benedict said he thinks that both the scholarships and the constant calls and emails from College Now are keeping application numbers up.

In Buffalo, the Say Yes city that’s the closest size and demographic comparison to Cleveland, a partnership between Say Yes and the University of Buffalo focuses on FAFSA completion throughout the year.

Nathan Daun-Barnett, a professor at the University of Buffalo who runs the project, said constantly reminding and helping students makes a big difference with FAFSA, which can be daunting to people not familiar with the forms.

About 40 interns and graduate assistants visit high schools during a normal school year to work with parents and students. This year, he and his staff switched to Zoom calls with families after schools were closed, which he said worked well.

So far this year, 49 percent of Buffalo seniors have filled out their FAFSA, compared with 48 percent last year.

He’s expecting a rush in FAFSA applications and college applications in the fall, once students see whether colleges will reopen and whether classes will be online. He suspects that when students also see a tight job market, college will look more attractive.

That rush in Buffalo and other cities would likely happen at local community colleges more than at four-year schools, and more at local schools than national ones.

“There could be a shift in the institutions students attend, with more opting to stay close to home [especially if colleges are delivering courses online] or perhaps take a semester or year off until in-person instruction resumes,” said Upjohn’s Miller-Adams.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)