Cleveland Teachers Take Lessons to TV to Stem Learning Loss, Stay Connected to Students Through Coronavirus

Laura Masloski held up a cardboard cutout of a circle for her preschool students to see.

“What shape do we have here?” she asked.

Masloski, who typically would be asking this question to a roomful of students, is now speaking into just her cell phone as it records. With schools shut down since March 13 because of COVID-19, the pre-K teacher at Cleveland’s William Rainey Harper Elementary School will not be able to hear her students calling out answers. Instead, preschoolers across Cleveland whose families tune in to her lesson will see it a week later on TV.

A partnership between the Cleveland Municipal School District and local Cleveland television WUAB CW43 has been putting lessons taught voluntarily by Cleveland teachers on air every weekday from 9 a.m. to 10 a.m. since April 20.

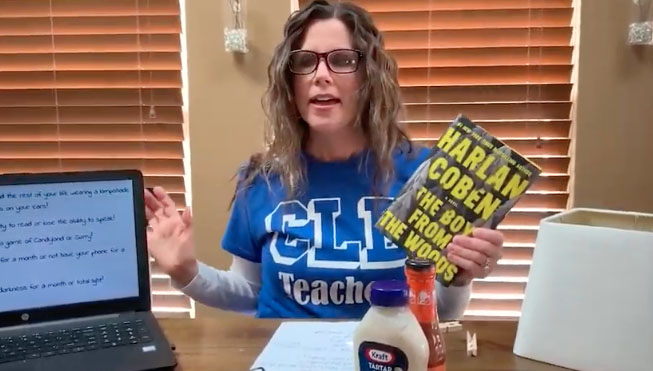

Teachers in grades 3-5 take their turn at “CMSD on CW43” Tuesday, with presentations that involve American Sign Language, a combination of math and baking, food science, music and making your own game. The virtual classroom can be seen 9-10 a.m. weekdays on WUAB. #celebrateCMSD pic.twitter.com/M2kivGsbPF

— Cleveland Metropolitan School District (@CLEMetroSchools) May 26, 2020

So far each of the nearly 30 episodes of “CMSD on CW43” has had a modest but loyal following of 2,000 viewers. It’s an effort by both the station and the district to reach as many students as possible in as many different ways as they can while schools are shut down. Preventing students from falling behind academically is a challenge across the country during the pandemic. But it’s much greater in Cleveland, where about 40 percent of families have no high-speed internet at home, other than through cell phones, and learning loss is a real concern.

Most families, though, have television.

“We know it’s an extremely targeted audience,” said Erik Schrader, the vice president and general manager of WUAB and a sister station. “It’s about the 40 percent of CMSD families that don’t have Wi-Fi access.”

“If we can keep the idea of educating kids top of mind … I think we’ve achieved something,” added Schrader, who was happy to air lessons each morning in place of a personal injury court show.

Masloski was eager to take on the extra work of preparing and recording lessons at home for her 4-year-old students.

“They don’t have access to the technology,” she said. “Their moms and dads aren’t giving them the phones and Chromebooks and saying, ‘Here, you need to learn all this.’ So this would be a really cool opportunity to see it on TV, because their parents do put them in front of TV while they’re trying to cook or clean.”

Kirsten Fischer, who teaches English for sixth- through eighth-graders at Cleveland’s Scranton Elementary School, said she missed her students and wanted to connect with them, even just on air.

“We want to serve the kids who do not have internet, the kids who technology is not available to them,” Fischer said. “This was a bridge, one more avenue for kids who weren’t able to get online to see us. We do the best we can to replicate lessons like we would in the classroom.”

When WUAB offered the district the time slot, the Cleveland Teachers Union reached out to winners of the district’s annual Excellence in Teaching Awards, which started in 2016. Nearly 20 of the winners volunteered and started setting plans, dividing up the days by age groups.

Monday is for grades pre-K-2, Tuesday for grades 3-5, Wednesday for grades 6-8 and Thursdays for high school. Fridays are for life skills lessons like cooking, aimed at all ages.

Each grade group, with teachers from multiple schools, acts as a team and meets on Zoom to coordinate plans for their next episode. Each teacher then records themselves, sometimes along with a teaching partner, doing a lesson for district staff to stitch together, along with an animated introduction, for the episode.

Special education teacher Kristen Lasley, who has taught most of the life skills lessons, started with cooking a dessert and then waffles — her daughter helping out on camera — before adding a car-washing lesson around Mothers’ Day.

“The first episode, it took 20 takes,” she said. “I had to stop my phone 20 times and restart 20 times because I either made a mistake talking or I paused too long. I was really nervous the first time, but now it’s second nature to me.”

Masloski had to invent ways to set her phone so it could record her, sometimes sitting, sometimes standing. With no tripod handy, she once wedged her phone into a roll of paper towels and stood it atop a storage bin.

She also had to relax and stop spending hours taping the lesson over and over. A conversation with her parents, she said, let her just ignore small errors and fumbles.

“They said, ‘If you would have done that in your classroom in front of your kids, what would have happened?’ ‘Oh, I just would have corrected it,’” she remembers. “‘Then do that. Stop trying to make it perfect all the time.’ They’re right. I’m in front of the kids talking, just like in the classroom.”

There have been a few other obstacles. Teachers needed to read on air only books without copyright limitations. And craft lessons needed to use only common items, so parents wouldn’t have to go shopping for supplies.

The audience, so far, has been modest. Schrader said he’s happy with the relatively small viewership since each represents a student learning more than they would have.

And teachers say they receive emails from parents constantly who say their children are watching and doing the lessons. Some even send pictures of their children watching the episode or doing the lesson. And one teacher received a picture of a student kissing the television because she missed the teacher badly.

Though the school year ended for most district schools last week, the teachers and station have agreed to keep doing the lessons all summer and even into the fall, if the reopening of school is delayed.

Lasley said continuing to have some connection between students and school matters, particularly since most summer activities at city pools and recreation centers are closed.

“Even if they catch one or two episodes during the summer, that’s more than doing nothing,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)