Chronic Absenteeism’s Post-COVID ‘New Normal’: Research Shows It Is More Common, More Extreme

Amid a wave of new research on the pandemic’s shattering effect on classrooms, one expert called it the ‘question that keeps me up at night.’

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The percentage of students with good attendance fell sharply between 2019 and 2023, while the share of chronically absent students more than doubled, offering further evidence of the pandemic’s shattering effect on the nation’s classrooms.

A new analysis of data from three states — North Carolina, Texas and Virginia — shows that prior to COVID, 17% of students were chronically absent, meaning they missed at least 10% of the school year. By 2023, long after schools had to cope with new variants and hybrid schedules, that figure hit 37%.

“Absences are both more common for everybody, but they are also more extreme,” said Jacob Kirksey, an associate professor of education policy at Texas Tech University.

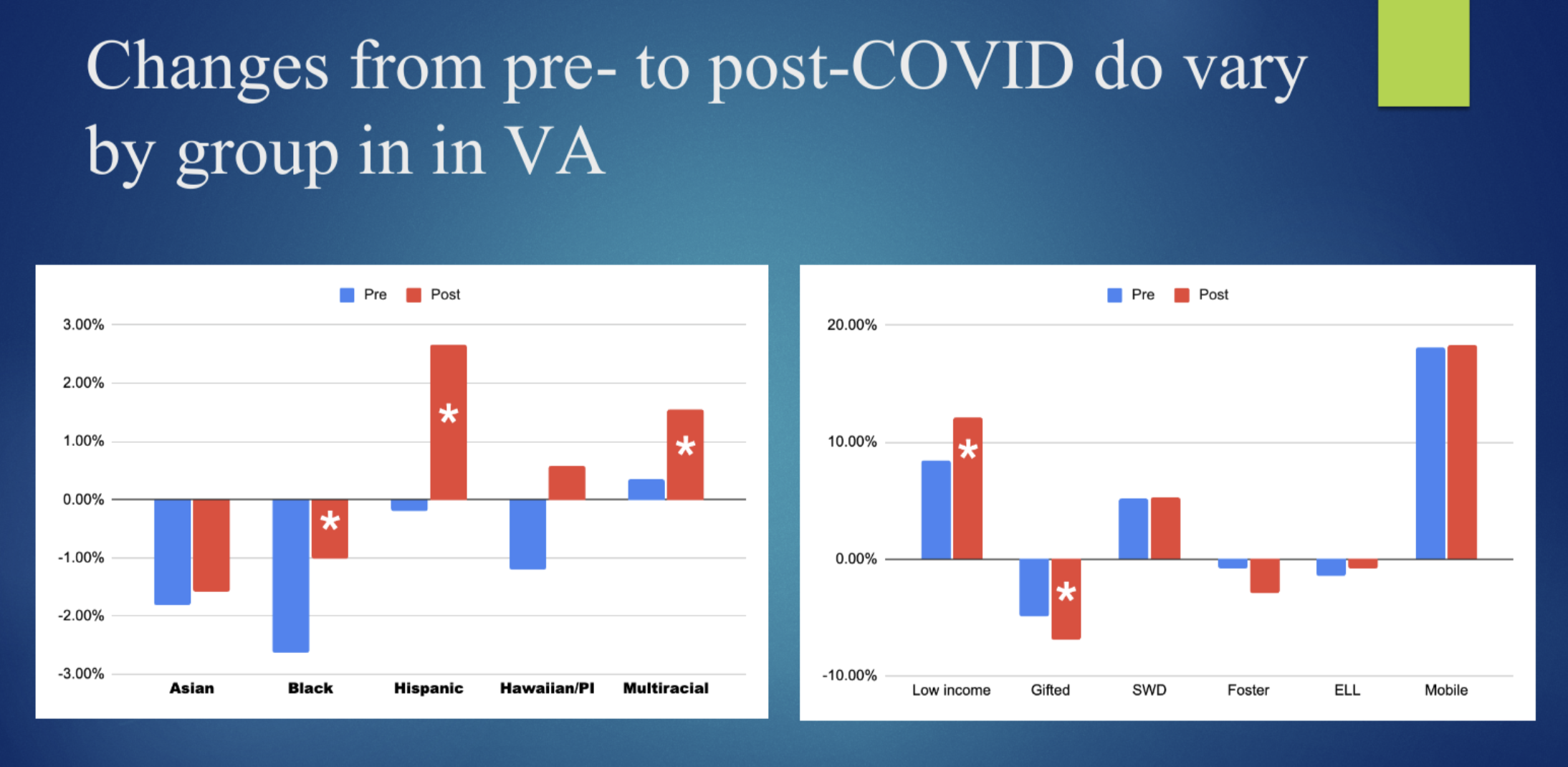

Additional new research shows that while post-pandemic chronic absenteeism lingers across the board, rates were substantially higher for low-income students. In North Carolina, for example, the chronic absenteeism rate for students in poverty before the pandemic was 9.2 percentage points higher than for non-poor students. By 2023, the gap increased to 14.6 percentage points.

“The income gap really was the main driver that showed up over and over again,” said Morgan Polikoff, an education researcher at the University of Southern California. But it’s hard for schools to make a dent in the problem, he said, if they aren’t investigating the reasons for chronic absenteeism. “There’s a big difference between the kid [who] has an illness and is chronically sick versus the kid [who] is super disengaged.”

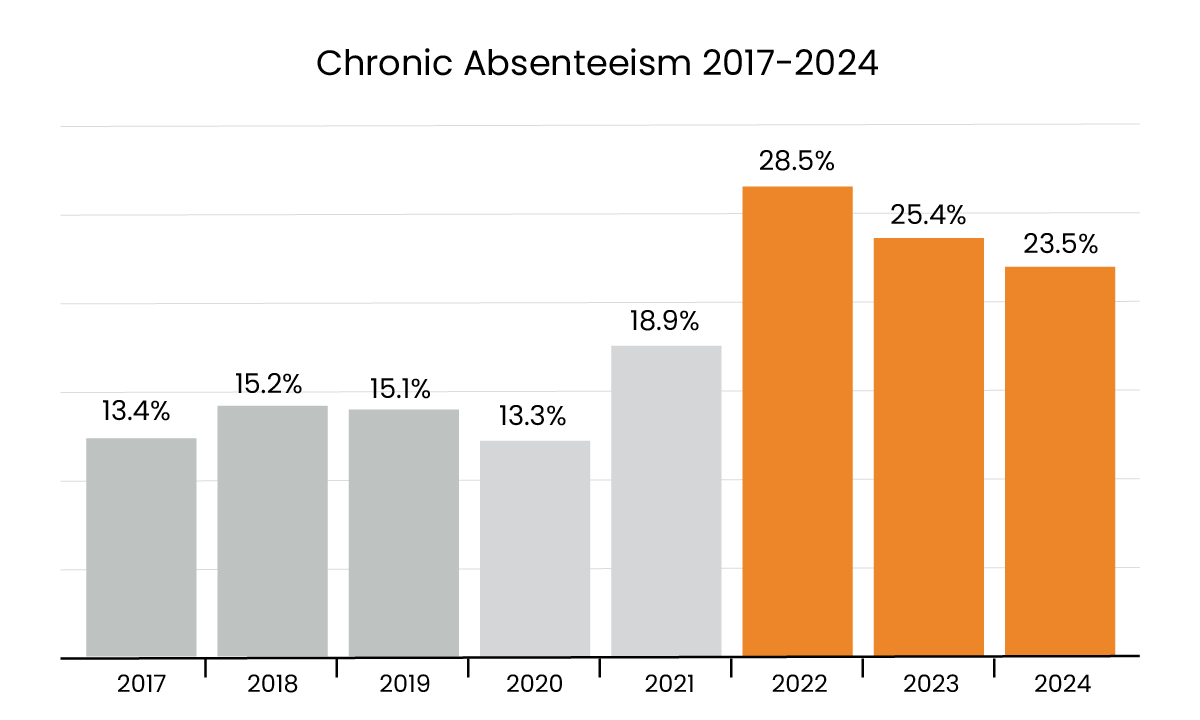

Kirksey and Polikoff were among several researchers who shared their findings Friday at an American Enterprise Institute event focused on facing what Kirksey called the “under-the-hood dynamics” of chronic absenteeism in the post-COVID era. Since 2022, when the national average peaked at 28%, the rate has dropped to 23% — still much higher than the pre-COVID level of about 15%, according to the conservative think tank’s tracker.

“I have a question that keeps me up at night. That question is ‘What’s the new normal going to be?’ ” said Nat Malkus, the deputy director of education policy at AEI. “We see this rising tide, but I think that it’s incumbent on us to say that chronic absenteeism still affects disadvantaged students more.”

The research project began in September with the goal of offering guidance to districts in time for students’ return to school this fall. The researchers stressed that those most likely to be chronically absent this school year — low-income, highly mobile and homeless students — are the same ones who will frequently miss school next year.

“Absenteeism should seldom come as a surprise,” said Sam Hollon, an education data analyst at AEI. “It’s hard to justify delaying interventions until absences have accumulated.”

Teacher absenteeism

One new finding revealed Friday contradicts a theory that gained traction following the pandemic — that students were more likely to be absent if their teachers were also out. As with students, teacher absenteeism increased during the pandemic and hasn’t returned to pre-COVID levels.

The relationship between teacher absences and student absences, however, is “pretty negligible,” said Arya Ansari, an associate professor of human development and family science at The Ohio State University.

“These absences among teachers don’t actually contribute to the post-COVID bump that we’ve seen in student absences,” he said. “Targeting teacher absences isn’t going to move the needle.”

The researchers discussed how even some well-intentioned responses to the COVID emergency have allowed chronic absenteeism to persist. States, Malkus said, made it easier to graduate despite frequent absences and missing school doesn’t necessarily prevent students from turning in their work.

“In my day, you had to get a packet and do the work at home” if you were absent, Polikoff said. In interviews with 40 families after the pandemic, 39 said it was easy to make up work because of Google Classroom and other online platforms. “How many said, ‘Let’s make it harder’? Zero.”

In another presentation, Ethan Hutt, an associate education professor at the University of North Carolina, estimated that chronic absenteeism accounts for about 7.5% of overall pandemic learning loss and about 9.2% for Black and low-income students — a “nontrivial, but modest” impact.

He stressed that missing school also affects student engagement and relationships with teachers. While technology has made it easier for students to keep up, “there may be other harms that we want to think about and grapple with,” he said.

From one to 49

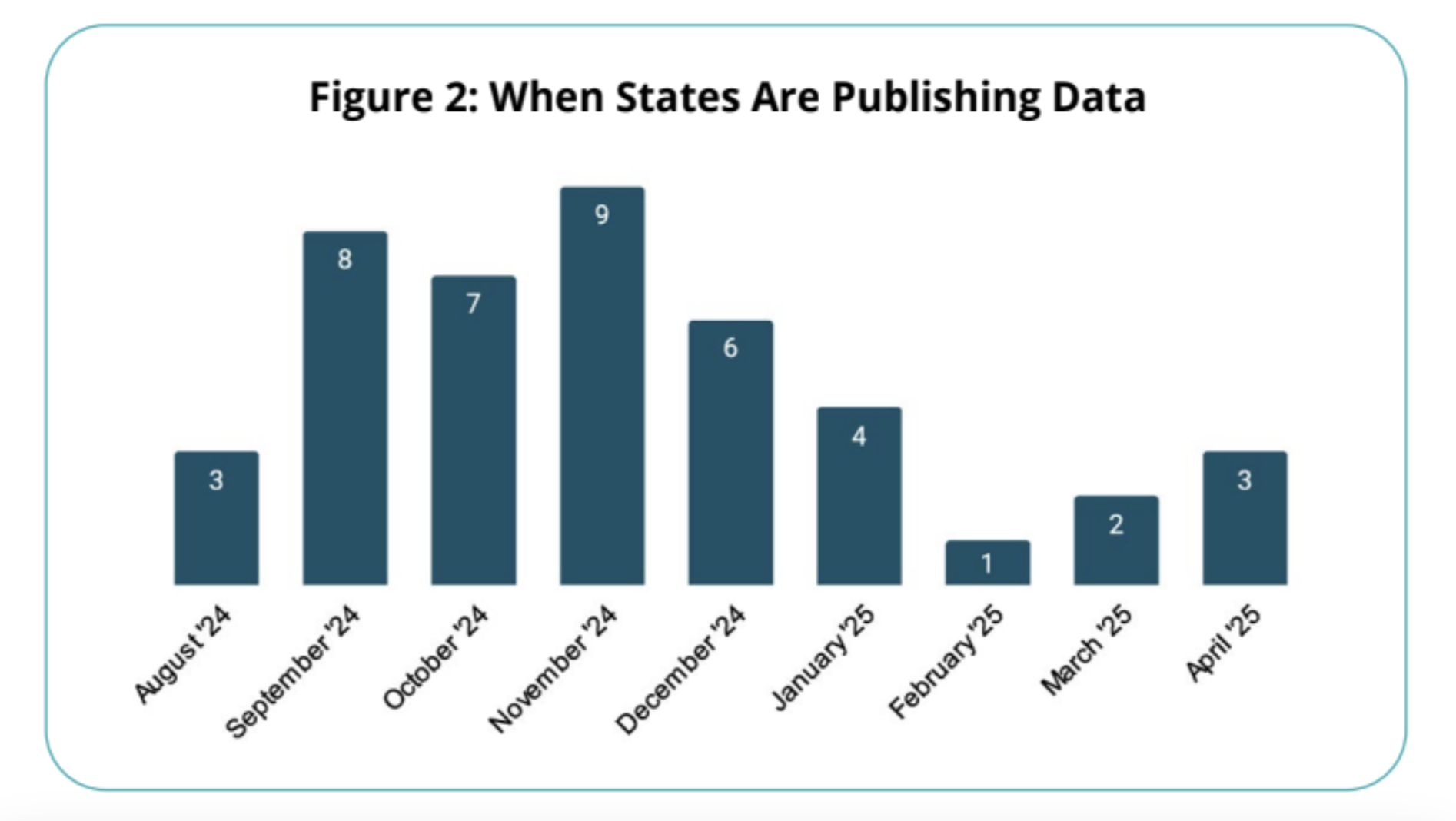

The new research comes as states are mounting new efforts to more closely track chronic absenteeism data and share it with the public. In 2010, only one state — Maryland — published absenteeism data on its state education agency website. Now, 49 states — all but New Hampshire — report rates on an annual, monthly or even daily basis, according to a new report released Tuesday by Attendance Works, an advocacy and research organization.

The systems allow educators and the public to more quickly identify which students are most affected and when spikes occur. Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Washington D.C. post rates even before the end of the school year. Rhode Island offers real-time data, while Connecticut publishes monthly reports.

The New Hampshire Department of Education doesn’t monitor chronic absenteeism, but has a statewide 92.7% attendance rate, a spokesperson said.

The report highlights states that have taken action to reduce chronic absenteeism. In Virginia, bus drivers ensure their routes include students who might be more likely to struggle with transportation. With state funds, Fauquier County, west of Washington, D.C., opened a center for students on short-term suspension to minimize the absences that tend to pile up when a student is removed from the classroom.

Overall chronic absenteeism in the state declined from 19.3% in 2022-23 to 15.7% in 2023-24. To Hedy Chang, executive director of Attendance Works, such improvement proves “we can still get things done in our country and in education, despite all of the culture wars and binary thinking.”

‘Priced out’

Some district and school leaders have looked to their peers for ideas on how to get kids back in school. After participating in a six-month program with 16 other districts across the country organized by the nonprofit Digital Promise, Mark Brenneman, an elementary principal in New York’s Hudson City Schools, started interviewing families about their challenges.

He learned that Hispanic parents often keep their children home when it rains because they’re worried they’re going to catch a cold. Several had transportation challenges. His school, Smith Elementary, even contributed to the problem, he said, by holding concerts, award ceremonies or other family events in the morning. Parents would come to celebrate their children’s accomplishments, then take them out for lunch and not return.

Hudson, about 40 miles south of Albany, has undergone significant change since the pandemic, added Superintendent Juliette Pennyman. Some families leaving New York City have settled in Hudson, driving up the cost of housing.

“Our families are being priced out of the community,” she said. “Housing insecurity was … affecting families’ and students’ ability to focus on school.”

As a result of the intense focus on the issue, Smith, which had a 29% chronic absenteeism rate last year, has seen an about a 15% increase in the number of students with good attendance.

“It’s not like we’re down to like 10% chronically absent,” Brenneman said. “But we’ve hammered away.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)