Children Are Asking Some of the ‘Most Powerful, Emotional’ Questions of Presidential Candidates About Gun Violence

Iowa

When it was time for Kamala Harris to take questions at an Oct. 7 town hall in Ankeny, Iowa, 12-year-old Nora stood up and told the California senator how scared she was to start school this year.

“I was afraid I was going to go in, and not come back out,” Nora said. “What is your plan to end gun violence so that way students can feel safe going to school?”

Similar scenes have unfolded at candidate events along the campaign trail when candidates hold town halls, allowing members of the public to ask them questions before the entire crowd. While citizens quiz presidential hopefuls about climate change, health care, student debt and other major issues, almost inevitably, kids ask about gun control.

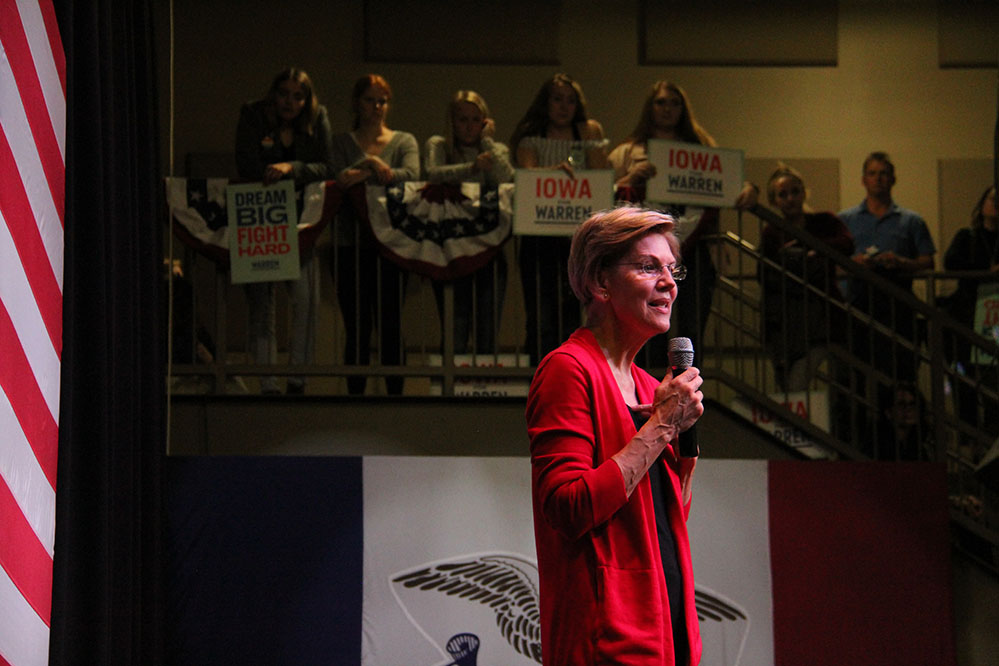

Last month, two students at Roosevelt High School in Des Moines questioned Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren about her plans for preventing gun violence. At North High School, also in Des Moines, four students asked former Texas representative Beto O’Rourke about his gun control proposals before he dropped out of the race.

“From the time I was in kindergarten, we’ve always had lockdown drills, and it’s just kind of baffling that’s still a reality especially in a country that prides itself on being safe,” said 15-year-old Olivia Vald, who asked Warren about gun violence at Roosevelt. “I think it’s something that could be fixed; it just takes courage from politicians.”

Gun control has become a bigger issue in the Democratic presidential primary race than in past election cycles, and it coincides with demographic shifts. Next November’s general election will mark the first time that citizens born after the Columbine shooting cast a presidential ballot. For voters under the age of 30 who plan to take part in the Democratic nomination process, 77 percent count gun violence as one of their main concerns.

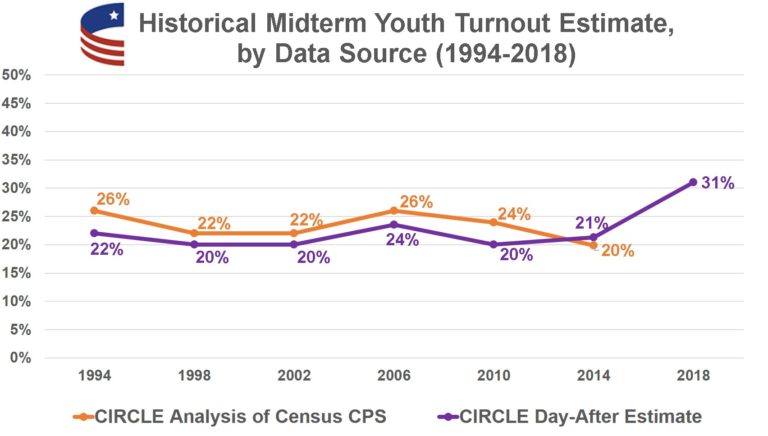

Following a 25-year high for youth turnout in the midterm elections, young voters are poised to play a larger role in the 2020 elections than the last race for the White House. With the growing political influence of Generation Z and their close scrutiny of gun control policies, the next president’s election will in part depend on who best convinces them that they have the best plan to prevent another gunman from opening fire in classrooms.

Sari Kaufman, a senior at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, sees a parallel between how her generation thinks of climate change and mass shootings; this is the reality they were born into, she said, because previous generations haven’t addressed the issue.

“The reason why young people are leading such a powerful movement is because of the authenticity behind it, because we’re going through it every single day,” said Kaufman, who will be voting for the first time next year and is working on youth voter registration drives with advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety.

The questions aren’t just coming from middle and high schoolers; elementary students have challenged the candidates on violence in schools as well.

Over the summer, 8-year-old Scout told New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker in Nashua, New Hampshire, that she is homeschooled in part because her family worries about gun violence in public schools. “And my question is, What do you plan to do about the school shootings?” Scout asked Booker, as members of the audience audibly gasped. In Austin, Texas, Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, choked up as he told a second-grader who asked about school safety that “we owe it to you” to make sure schools are safe.

“I’ve been working on the intersection of politics and gun safety for five years now, and hands down, the thing that resonates the most with voters of any age is this idea of school safety and how terribly we’ve failed children on this issue,” said Joanna Belanger, political director at Giffords, the gun control reform group founded by former Arizona representative Gabby Giffords, who survived a 2011 assassination attempt in Tucson, Arizona.

The fear infecting schools is more salient than concerns about gun violence in other public places because of how easy it is for people to put themselves in the shoes of students, Belanger noted. Nearly everyone has gone to school or has sent their children off to one, while people may not have been to a “Congress on Your Corner” event like the one where Giffords was shot.

All the prominent Democratic candidates have gun control platforms and pledge to stand up to the National Rifle Association. Many of them also appeared at a gun safety forum in Las Vegas in October. Candidates typically haven’t waded into debates about monitoring students’ social media or spending money on bulletproofing campuses, but they have offered other proposals in response to the students.

When Harris answered 12-year-old Nora’s question about her plans for school safety, the California senator vowed to take executive action to put in place a comprehensive background check system if Congress didn’t put a bill on her desk in the first 100 days of her term as president.

O’Rourke had unabashedly said he’d confiscate military-style assault rifles and ban high-capacity magazines. Warren noted that gun violence extends beyond mass shootings at schools, and while she supported expanding background checks and getting “weapons of war” off the streets, she said the issue has to be treated as a “national health emergency” that requires ongoing policy changes.

Ivee Williamson, 17, another Roosevelt student who asked Warren about her gun control policies, told The 74 that she’s lived through enough campus lockdowns that left an impression, including one that happened as she and her peers were preparing to go to a middle school dance.

“That was just a really scary moment to see all my classmates crying, hugging each other, not knowing what’s going on,” Williamson said. “Just watching the media, everything going on in our world, it’s extremely scary, and I don’t think anyone thinks you should come to school scared; it’s just not right. I want to be a teacher, so when I grow up I don’t want to have to be worrying if my kids are scared to come to my classroom. I don’t want to be scared myself.”

This map includes school shootings that took place on campus in 2018 where a person was injured or killed. Incidents resulting in injury are labeled blue, while incidents resulting in death are labeled red. The most recent incident is indicated with a larger icon. Click on the icons to see details about each incident.

School shootings are statistically rare. However, by some measures, mass shootings have become more frequent and the incidents deadlier. Attacks at schools in recent years that shocked the public consciousness, like the 2012 shooting that killed 20 elementary schoolers in Newtown and the shooting in Parkland where students shared footage of the carnage on social media, have resulted in a state of terror for students nationwide.

Fighting back tears, a 14-year-old at Berg Middle School in Newton, Iowa, told O’Rourke how afraid she was to go to school, and asked what actions he’d take to “protect people like me and my classmates.” O’Rourke told The 74 it was “one of the most powerful [and] most emotional questions” he had heard on the campaign trail.

“She’s seen those in positions of power and public trust do absolutely nothing to address gun violence despite all of the school shootings, or mosque shootings, or church shootings, or Walmart shootings in this country,” O’Rourke told The 74. “The encouraging thing is that so many young people are raising this as an issue that matters to them.”

No candidate has focused as much on gun violence as O’Rourke, who made it a key issue in his campaign after the Walmart shooting in his hometown of El Paso, Texas. O’Rourke withdrew from the presidential race on Nov. 1, but a week before he bowed out, he faced several questions from teens during a stop in Des Moines at North High School — one of the most diverse student bodies in Iowa. Eric Samuka, the 18-year-old senior class president, asked O’Rourke what his plan was to prevent another shooting like the one in El Paso. “Because if that happens down south, me or any of my peers could be the next person who gets shot down,” Samuka said.

O’Rourke discussed his plan to ban and confiscate assault rifles like the AR-15 and AK-47, and he said he was confident that people will largely follow the law.

But later on, 16-year-old Delicia Oxenreider pressed O’Rourke on his plan to ban military-style rifles, because she worried it would increase the demand for them on the black market. “If they’re sold illegally, then we don’t have any control over who has them,” Oxenreider said. Oxenreider told The 74 she wondered why candidates weren’t discussing how to “fix our counseling systems, and maybe train our teachers to look for warning signs.”

People make threats against North High School online “all the time,” Oxenreider said, though she thinks someone who’s serious wouldn’t tweet about it first. “I feel like no one would be dumb enough,” she said, “because we do have our officer here, and I mean, half these kids have regular guns.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)