Charter School Promising ‘LGBTQ-Affirming Learning Environment’ Set to Open this Fall in Alabama

Michael Wilson has worked as an educator in Birmingham, Alabama, for more than two decades, but it wasn’t until this year that he has felt that he can bring his true self to work.

Wilson, 67, is founding principal of Magic City Acceptance Academy, a charter school opening in fall 2021 that promises in its mission statement to provide a “safe, LGBTQ-affirming learning environment.”

“It’s the first time in my life, where I have a job doing what I love to do, and what I’m passionate about doing. And I can be myself,” he said. “I can be an openly gay man — and say that to teachers and to parents and the students. And it’s OK. And, then I’m able to say, whoever you are is OK, too.”

For years as a teacher and then a principal in Birmingham City Schools, “nobody asked, and I didn’t say anything [about my sexual orientation],” said Wilson, who was named Alabama’s distinguished principal of the year in 2019 for his work at a district elementary school.

Now, he’s at the helm of the first school in Alabama — and possibly the country — to enshrine welcoming language for LGBTQ students in its mission statement. Magic City will open this fall to students in grades six through 12, and it plans to welcome 250 to 300 students across those grades. The school will be open to all students — regardless of whether they identify as LGBTQ — and will institute a lottery if there are more applications than seats.

The establishment of the school “sends a clear signal” that LGBTQ students are valued, said Kate Pimmel, chair of GLSEN Huntsville, the only Alabama chapter of the LGBTQ advocacy organization. She outlined four things that make a school culture “affirmative”: inclusive curriculum, supportive educators, student-led clubs, and policies that specifically ban bullying and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender representation or other LGBTQ-related reasons.

“For the first school of this kind to exist in Alabama means a school like this can exist anywhere. That’s a source of hope for all of us,” Pimmel said.

Birmingham AIDS Outreach, a nonprofit founded in 1985, conceptualized the school and is the force behind its creation.

Karen Musgrove, executive director of Birmingham AIDS Outreach, said she was motivated to open the charter school because so many of the students in the organization’s after-school program were being bullied. Many were disengaged or dropping out of school and “didn’t see that Birmingham was a place where they could grow or see that Birmingham was a place that wanted them,” and couldn’t envision a future beyond part-time jobs at fast-food restaurants, she said.

“I want these students to come to school and talk to mentors and see that their city is thriving and see that there’s a place for them,” she said.

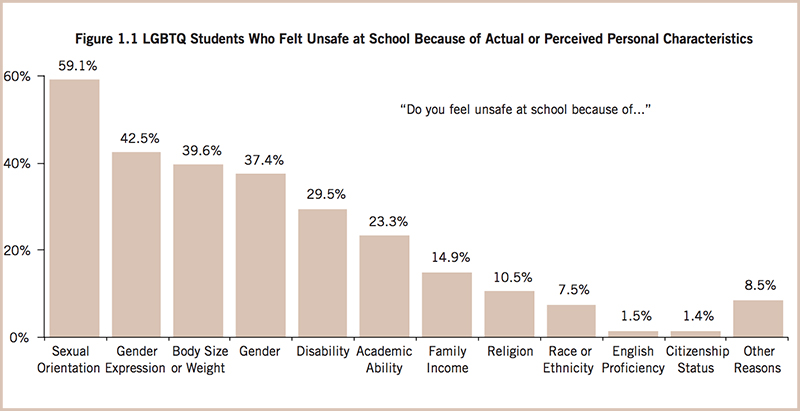

About 17 percent of LGBTQ students across the U.S. reported changing schools because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable, and nearly 33 percent said they had missed school in the past month for the same reasons, a 2019 survey by the advocacy group GLSEN found. Students in the survey who experienced discrimination at school were more likely to say that they had missed school recently and reported lower grade point averages, self-esteem and school belonging.

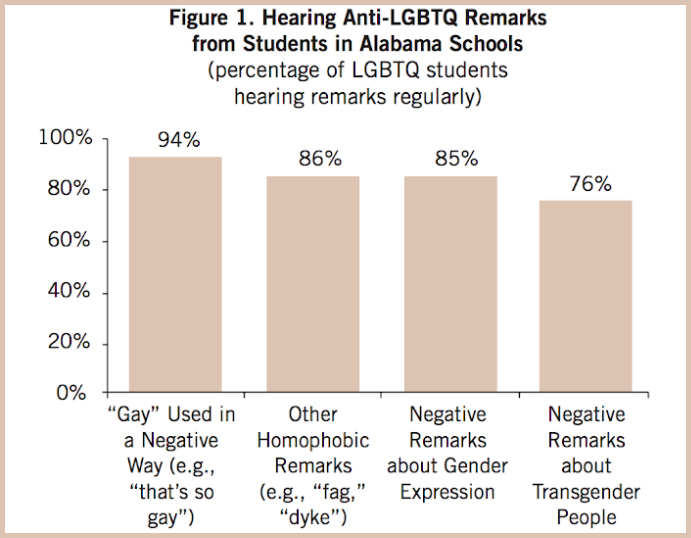

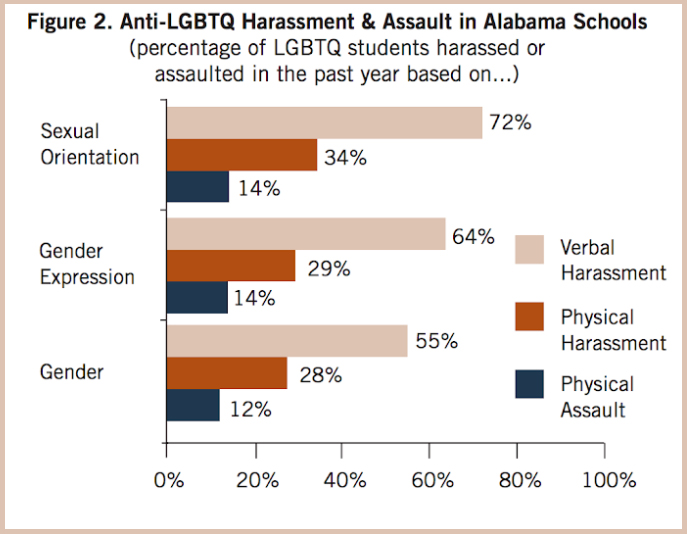

Of Alabama students surveyed, 94 percent said they regularly heard other students use the word “gay” in a negative way, and 72 percent reported verbal harassment because of their sexual orientation.

LGBTQ students in the south are more likely to have “negative school experiences” than those in other regions of the United States, and less likely to have access to LGBTQ-related resources, according to the GLSEN report. Only 4 percent of Alabama students said their school had a “comprehensive anti-bullying/harassment policy that included specific protections based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression,” and 16 percent said their school administration was very or somewhat supportive of LGBTQ students.

Hiring a diverse group of educators who have a “passion for teaching and learning” is a priority for the school, Wilson said, and the staff plans to emphasize personalized and project-based learning. Educators will be trained in restorative justice and trauma-informed instruction as well. Professionals from the wider community will also mentor the students to help expose them to opportunities in Birmingham beyond their school and part-time jobs.

Although Magic City Acceptance Academy has gotten attention for its explicitly welcoming language for LGBTQ students and the founders want LGBTQ students to know it is an option for them, Wilson stressed it will serve “whoever walks through our doors.” Students who have been bullied for other reasons or experienced trauma could also benefit from the school’s approach and wraparound services, he added.

“We want them to see that there is an alternative and they can still be who they are,” Wilson said. “They don’t have to change who they are in order to be successful.”

Students will have access to the organization’s existing support system, including a free after-school program and health center in Birmingham. The school itself will be in Homewood, Alabama, “literally almost feet outside the city limits of Birmingham,” Wilson said.

Wilson and his colleagues first planned to open the school in Birmingham proper but had to change course during what he called an “arduous” process from application to approval.

Alabama state law has allowed charter schools since 2015 but the state has only five so far, and Birmingham has just two. A handful more are slated to open around the state this year. Districts can opt in to being authorizers, and charters wishing to open within the bounds of a district that is an authorizer must apply to their district board of education, which can see new nontraditional schools as competition. Schools wishing to open in a district that is not an authorizer can apply directly to the Alabama Charter School Commission.

The Magic City team first applied to the Birmingham City Schools board of education for a charter but was denied. After appealing the decision and being denied again, the team selected the Homewood location, where the local district is not a charter authorizer. The team revamped its application, emphasizing its focus on trauma-informed instruction, and applied directly to the state charter commission and was again denied — twice.

Magic City’s attorneys asked for a review of the denial. The commission completed the review, voted again and finally granted the charter in November. Registration for the lottery opens Sunday.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)