Charlottesville Summit, 30 Years Later: Lamar Alexander on the Governors’ Gathering That Changed Education, Leadership, ESSA and How Politics Is Like Kindergarten

To commemorate the 1989 Education Summit in Charlottesville, Virginia, that convened 49 of the nation’s 50 governors to discuss a single policy issue — the education of America’s children — the Aspen Institute’s Education & Society Program is partnering with The 74 to produce a series of Q&A’s with distinguished leaders across politics, education and advocacy to reflect on the legacy of the summit and what lies ahead for public education. The interviews were conducted over the telephone, transcribed and edited for clarity and length. Participants were asked some of the same questions, but also queried specifically about their careers and backgrounds. These leaders share their thoughts on why the summit was a groundbreaking event, the strengths and shortcomings of education policy and what is required for propelling further gains for students. You can see all the interviews here.

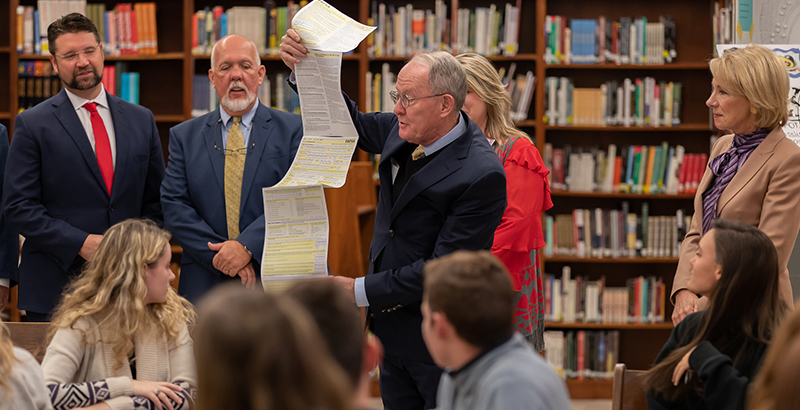

The son of educators, Republican Sen. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee has spent decades advancing education policy. He served as governor of Tennessee, president of the University of Tennessee and U.S. secretary of education, and he is now chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee. In 2015, he, along with Democrat Patty Murray, shepherded the development and passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, which replaced the No Child Left Behind Act. In this interview, Alexander reflects on how the 1989 Education Summit set the template for current federal education policy, the leadership of Southern governors during the event, the “Christmas miracle” of the Every Student Succeeds Act’s passage and the parallels between kindergarten and politics.

What were the most significant accomplishments from the 1989 Education Summit and the standards-based agenda that emerged from it?

The combination of the summit in 1989 and President [George H.W.] Bush’s strategy for implementing the goals established at the summit created the federal education policy we have today. The summit didn’t even invite members of Congress because they didn’t want the members of Congress involved in telling the states how to rate the schools.

The agenda from the summit created the goals, the standards and the tests to see whether anyone was reaching the goals. It involved the nation’s governors in a continuing effort to implement all that and created a federal education policy which, in my opinion, is about the right balance. We’ve settled back to about where we were when Bush left office, which was, No. 1, national education goals, which the governors agreed on in 1989, and No. 2, an expanded Nation’s Report Card so that you could have reliable state-by-state comparisons of whether students were succeeding.

Since the summit, we’ve had the rise and fall of the “national school board,” an overactive U.S. Department of Education. We moved toward that with President Bill Clinton’s Goals 2000, which Bush objected to. Then we had [President] George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind, which arguably was more like a state education law; it was more prescriptive. And then, President Barack Obama and [his education secretary] Arne Duncan went even further with implementing No Child Left Behind through the use of waivers to try to tell states what to do about how to evaluate teachers, how to fix schools that were falling behind and what standards they needed to have.

All that led to the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, which was a collective effort that included governors, teachers unions and Congress saying we’re tired of Washington telling states and local school districts so much about what to do with their schools. It restored the level of autonomy and state responsibility that existed at the end of President George H.W. Bush’s term. That’s why I would argue that the effect of the summit was to create the federal education policy structure that exists today.

Southern governors stepped up to prioritize education and in some ways created the architecture of the 1989 summit. Why were Southern governors such leaders in this work?

Two reasons. First, a number of us were all elected on the same day. Bill Clinton, Bob Graham, Dick Riley and I all were elected in November 1978 in states that adjoined one another or were close together. William Winter in Mississippi was already in office. We were similar in age and beginning our governorships at about the same time. Second, and probably more important, we all had a common problem to solve. Our states were economically behind, our family incomes were much lower than the rest of the country and all of us came to the conclusion about the same time that better schools meant better jobs. We began to work together through the governor’s associations and our friendships on different ways of improving teacher quality, setting higher standards, what to do about schools that were falling behind, how to have better tests.

About the time we were elected to our second terms, the Nation at Risk report came out during President Ronald Reagan’s administration in 1983 and produced more of a national response for the need to improve schools. But we were already well along by the time that came. Then, in 1985 and 1986, I was chairman of the nation’s governors, and Bill Clinton was the vice chairman, and we agreed that the governors would spend the entire year on one subject, and that was education, and that hadn’t been done in a century, just spending it all on one subject.

That state-by-state initiative and then our National Governors Association effort, called Time for Results, led toward the summit. The summit never would have happened if so many governors, especially Southern governors, hadn’t been working in their own states on the same issues.

On shaping the national conversation, I think it’s fair to say the discussion in the 1970s on elementary and secondary education was about racial justice, social inequity and economic equity. In the 1980s, the focus didn’t leave those issues behind, but it shifted attention to accountability, results and that low-income states and low-income students were best served by helping them actually learn something so they could succeed in the world.

In 1984, Tennessee became the first state to pay teachers more for teaching well, but Florida was right behind us trying to do the same thing. And Arkansas was focusing on improving teaching, too. The focus shifted from equity to results, and the governors were leading that charge.

You’ve written about the importance of education for citizenship and for character development. Was there an unintended consequence of shifting focus and attention away from those areas as the standards-based accountability movement gained steam?

It was a larger accomplishment than most people thought to say our goals are math, science, English, history and geography. That meant that the school curricula across the country shifted in that direction, and that means there’s less time for music and art and less time for character education.

As far as civics education goes, that was gradually being replaced by social studies, which I never agreed with, because I liked [former teachers union chief] Albert Shanker’s definition of a public school, “A public school is for the purpose of teaching immigrant children reading, writing and arithmetic, and what it means to be an American, with a hope that they would go home and teach their parents.”

Shanker was an old-school, old-fashioned, anti-communist, liberal patriot who believed that one important purpose of a public school was to help students understand what it meant to be an American, what is distinctive about our country. By the 1990s, the worst-performing subject in high school Advanced Placement tests was not math or science, it was U.S. history.

Can you articulate what the federal role ought to be relative to state leadership? What is the role of state leadership relative to community leadership?

The federal role should be, No. 1, bully pulpit. For example, in 1984, Reagan came to Knoxville to Farragut High School in Tennessee to say that the master teacher program I had proposed would be good for the country. He didn’t arrive with a pot of money or with a federal mandate to make anybody do it. But he was a big help in getting the state to adopt it. The bully pulpit, pointing out what goes well or, as when [Education] Secretary [William] Bennett went to Chicago and said, “These are the worst schools in the country,” pointing out what’s not going well, that can be enormously powerful.

No. 2, I think during the last 30 years we’ve agreed that it’s useful to have the state tests that were required by the federal No Child Left Behind law of 2002 that disaggregated student results so we can see if children are actually being left behind in the core subjects. We should keep that, and we agreed to do that with the Every Student Succeeds Act.

“If you want something to have broad acceptance and to last a long time, you need buy-in from all parts of the community, and that usually includes some of your political adversaries. The work that we did in the 1980s as governors was completely bipartisan. We checked our politics at the door.”

But a third example of the federal role should be restored to states, which is what we did when we fixed No Child Left Behind, and that is the major responsibility for figuring out what to do about the test results. What does that mean in terms of evaluating teachers? What does that mean in terms of adopting accountability systems? What does it mean in terms of coming up with ways to turn around schools that are having a hard time?

If I were governor today, I would probably be doing exactly what I did in the 1980s, which is pushing for higher standards on the national goals and effective tests to measure progress toward the goals. I’d be trying to reinstitute the master teacher program.

We’re living through a time of polarization that has made its way into education policy debates. You’ve led political processes that have created bipartisan consensus. Do you have any advice for governors and state leaders about how they might grow a bipartisan spirit in education policy making?

I don’t think it’s that complicated. If you want something to have broad acceptance and to last a long time, you need buy-in from all parts of the community, and that usually includes some of your political adversaries. The work that we did in the 1980s as governors was completely bipartisan. We checked our politics at the door.

One of my favorite examples is Florida and Tennessee were competing to see who could be the first state to create a master teacher program, where some teachers were paid more than others based upon their excellence. Yet Bob Graham, the governor of Florida, stopped in Nashville in 1984 on his way home and met privately with the Democratic chairman of the state Senate who had the decisive vote on whether Tennessee would succeed with its plan. He helped persuade her to do it and then went on back to Florida.

That Democratic governor advocated for an issue that was heavily opposed by the National Education Association, which was an important constituent in Democratic politics then and now. He was willing to do that in a bipartisan way to help children. But we still see that today. When we fixed No Child Left Behind in 2015, a lot of people said it couldn’t be done, that the world of elementary and secondary education was too partisan and too difficult. I remember Duncan told me he thought the odds were 10 to 1 we wouldn’t succeed.

But when we marked the bill up in the Senate committee, which included 22 senators ranging from Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders to Rand Paul, the vote was 22 to 0. It was unanimous. When we eventually passed the Senate, it attracted 85 votes, and when Obama signed it in December, he called it a Christmas miracle. It’s very possible to work in a bipartisan way. In fact, the only way to create a lasting result that everyone buys into is to do it that way.

It still could happen, but it happens by lessons you learn in kindergarten. I work a lot with Patty Murray, the Democratic leader of our committee. She used to be a kindergarten teacher, and you learn to work well together, you don’t surprise one another, you learn to trust one another, and then you work on the things that you can agree on. If we follow a fairly simple formula, like the governors were able to do in the 1980s, we senators can do it 30 years later if we just put our minds to it.

We had the teachers unions, as well as the National Governors Association, in strong support of what we did to fix No Child Left Behind. As a result, I think classroom teachers in 100,000 public schools can know that federal education policy isn’t going to change for eight, 10 or a dozen years because we hammered out the differences of opinion, came to a consensus and got a result.

Ross Wiener is vice president at the Aspen Institute and executive director of its Education & Society Program. Previously, he was vice president for program and policy at the Education Trust and a trial attorney in the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Educational Opportunities Section.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)