Caught in a Financial ‘Triple Squeeze,’ Districts Could See Annual Costs of $2,500 Per Student to Address Pandemic-Related Learning Loss

This article is one in a series spotlighting the broader consequences of families disenrolling their children, students changing schools and children going missing amid the coronavirus crisis. See all our coverage at ‘COVID’s Missing Students.’ (If you or a student you know changed schools or stopped going to class altogether because of the pandemic, tell us your story. On Twitter: #WhereAreTheKids and #IAmHere)

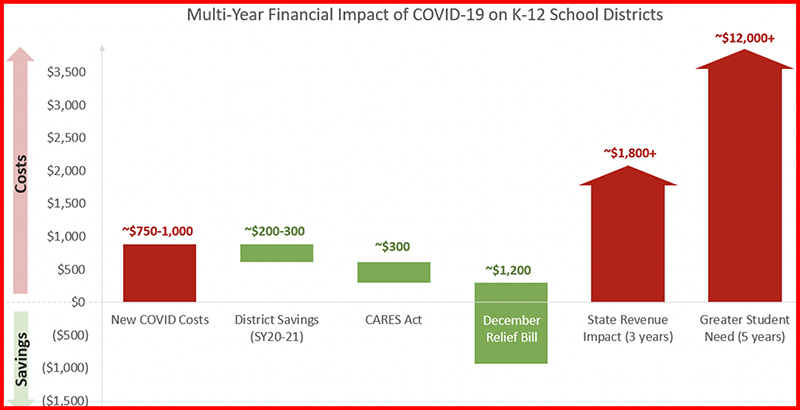

Getting students to where they’d be academically if the pandemic hadn’t occurred could cost schools an average of $12,000 to $13,500 per student over the next five years, according to a new estimate that assumes most will need some additional learning time.

Conducted by Education Resource Strategies, a nonprofit consulting firm that works with districts on financial issues, the projections account for the kind of “high-dosage” tutoring needed for students who have fallen the furthest behind and hiring more staff devoted to schoolwide social-emotional learning efforts.

The costs, roughly $2,500 per year, follow recent research showing that while declines in student performance weren’t as steep as predicted earlier, the students expected to be the most impacted by school closures didn’t even take tests that would determine where they stand.

“We wanted to broaden people’s perspective on what the full cost of COVID is,” said Jonathan Travers, a partner at the firm and a co-author of the paper with Tiffany Zhou, a principal associate. He said they were concerned that conversations among district leaders and policymakers focused more on immediate technology needs, masks, sanitation costs and the loss of state revenue — all of which are “dwarfed in comparison” to the need for academic remedies.

Districts are caught in a “triple squeeze” of rising costs, flat or declining revenues and increased student needs, according to the paper, which was shared with The 74 in advance of its expected publication Wednesday. The calculations — which apply generally to urban and countywide districts with large concentrations of poverty — could serve as a guide as governors and state lawmakers begin to consider budgets for the 2021-22 school year. In California, for example, Gov. Gavin Newsom said helping students recover learning they’ve missed is “not only top of mind, but it’s foundational in terms of the budget.” And with President-elect Biden calling the $54 billion schools are receiving from the most recent relief bill a “down payment,” the analysis could also inform plans for future funding bills.

“The price tag will be high,” Biden said last week about his stimulus plan.

‘Not a windfall’

The newest allocation of relief funds flows only to Title I schools and amounts to roughly $1,000 extra per pupil, which could pay for some learning-related expenses, Travers and Zhou predict. According to the law, districts have to spend their portion by September 2023.

While that potentially covers districts’ efforts to focus on learning gaps this school year and the next two, Travers and Zhou wrote that “investments to address increased student need will span multiple years.”

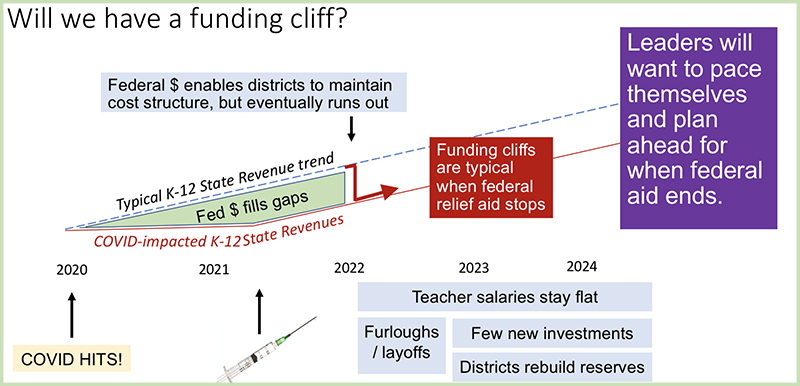

In a recent webinar, Marguerite Roza, who leads the Economics Lab at Georgetown University, explained the pandemic might be in the “rearview mirror” before districts experience its worst financial effects.

“It’s not a windfall for sure,” she said, and districts need to pace themselves to avoid what experts refer to as a “funding cliff.” She added that while districts have wide flexibility in how they can use the funds, the Department of Education will be looking for evidence that they addressed learning loss.

Travers recommended districts follow three steps: calculate where students are academically — compared to where they normally would have been without school closures; decide what strategies to use to address the gaps; and then, determine the cost.

Many districts have already started that process.

In the Ravenswood City School District, in California’s Bay Area, assessment data “suggests that our students may come out of the pandemic roughly a year behind where they typically would be,” said Lara Burenin, director of curriculum and instruction.

The district has redirected 10 percent of its budget — about $45 million — toward additional academic support, and expects it will cost an extra $5,000 to $8,000 per pupil over the next five years to bring students back to grade level.

Across the country in Cincinnati, Ben Lindy, a member of the school board’s finance committee, said, “I think the data are likely to show we’ve got a multi-year issue ahead of us.” The district is considering a range of approaches including summer school, extended-day programs and tutoring.

“Equity in this context means we should focus most on the kids who have been hit the hardest,” Lindy said. “Ultimately, I’m sure we will have to make hard decisions about what we are able to fund, and any federal or state help that becomes available will be a big deal.”

‘A continuous process’

According to the paper, additional instructional time — such as extending the school day and year, or adding summer school — would address seven to eight months of learning that students have missed due to the pandemic. The targeted tutoring, they wrote, would recover another three to five months of learning. But those ranges would vary by district and would be less if students return to the classroom sooner than expected or the quality of remote learning continues to improve.

Since last spring, several experts and district leaders have said that if there was ever a time to break out of the traditional school calendar, now would be it. Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam and lawmakers in Mississippi are among those who have recently discussed implementing year-round school calendars.

Nationally, 43 percent of district leaders indicated they were planning to “adjust policies regarding instructional time,” according to a recent survey from the RAND Corp. One in five districts responded they want to provide tutoring to students, but lack financial resources.

Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the California State Board of Education — and head of Biden’s transition team for education — discussed learning time recently in connection with Newsom’s school reopening plan. His proposed 2021-22 budget, released last week, includes $4.8 billion to expand learning time, including summer and afterschool programs, as well as $400 million for school-based mental health programs.

“We need to understand the school year in new ways. We’ve been tied to an agrarian calendar for the school year,” Darling-Hammond said during a press conference. “Many districts want to and will be supported to continue to expand the school year, to offer school in the summer. We should think about this as a continuous process.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)