Updated August 16

Neglect and arguably education malpractice have been the shameful hallmarks of public schooling for many Native American students so it’s no surprise that when the state of Arizona finally offered another option, the parents of those children rushed to embrace it.

In 2015, Native American families for the first time were allowed to tap into Arizona’s education savings account, state funds that parents can use to pay for private school tuition and other educational options.

“When I heard about the [new funding], I jumped at it,” said Tamelia Boyd, who used it to re-enroll her three high schoolers in St. Michael Indian School, a 100-year-old Catholic institution on the Navajo reservation that had become too expensive for the family. “That was a main factor in our decision to send them back.”

But in the strange bureaucracy that has governed Indian education in America since the 1800s, that door was not opened to all students living on tribal lands in Arizona. The children attending schools run by the Bureau of Indian Education, schools exclusively funded — and, for decades, wildly mismanaged — by the federal government were left out. The reason? The federal dollars that pay for their BIE schools can’t be diverted into parent-directed ESA accounts like the Arizona state dollars that follow their tribal neighbors.

State Sen. Carlyle Begay, a member of the Navajo nation and sponsor of the expanded ESA eligibility bill, said 100 families of students in BIE schools applied for the funding last year but had to be turned away. Begay himself attended a BIE boarding school as a kindergartener and remembers his parents having to bribe him with a toy rocket to get him to go.

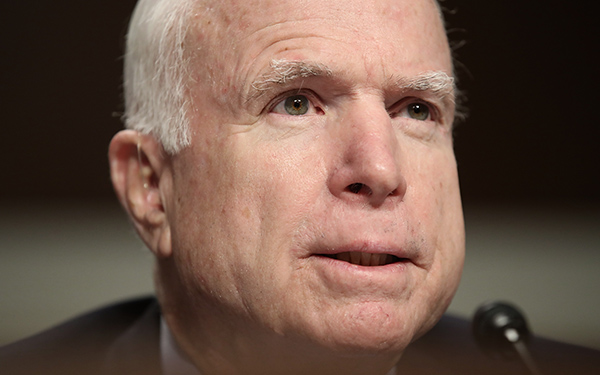

Republican Sen. John McCain, who has represented Arizona in Congress for decades, in March introduced the

Native American Education Opportunity Act to try and remedy the disparity that excludes BIE students.

The bill would allow students attending BIE schools in states with education savings accounts to use federal funds in ESAs. The BIE students would receive either 90 percent of their per-pupil BIE expenditure, or the same amount they’d get from the state, whichever is less.

“You cannot make an argument that the BIE schools have not failed. There’s study after study, story after story about the terrible conditions that exist in BIE schools,” McCain said in a recent interview with The 74. “There’s no measurement that would indicate that BIE schools are doing anything but failing.”

There are currently BIE schools in 23 states, most clustered in North and South Dakota, Arizona and New Mexico. All five states that offer education savings accounts — Tennessee, Florida, Mississippi, Nevada and Arizona — are home to at least one BIE school.

Although the idea seems pretty simple — give students at BIE schools the same opportunities available to their peers at state-funded schools — passing the bill is far from a done deal. McCain, long known for his reputation as a straight shooter, is candid about the chances of it passing by the end of the year: “I think it’s poor.”

Students graduate from St. Michael Indian School. (Photo by RAH Photography, Courtesy of St. Michael Indian School)

Even passing the original Arizona bill expanding eligibility to Native American students was tough; it squeaked through the state House by three votes, and only on the second attempt. Begay, the bill’s sponsor, switched parties from Democrat to Republican, in no small part because of his old party’s opposition. The American Federation for Children, an advocacy group that promotes vouchers and education savings accounts, has backed Begay’s efforts, and AFC founder Betsy DeVos and her husband Dick both donated to Begay's since-suspended campaign for U.S. House.

“The [ESA] program was simply, in my mind, a part of a solution to a larger problem,” Begay told The 74. “We tend to, in political debate, focus on the systems of education rather than simply trying to focus on solutions. The ESA program in Arizona and the expansion of the program to include tribal communities is simply an attempt to resolve [educational disparities] and give an opportunity to families and children to choose the type of education that they wanted.”

Public schools serving Native American children in Arizona are some of the lowest-performing in the state, Begay said. The graduation rate for Native American students in Arizona was 61 percent in 2013, below all other demographic groups except those with limited English proficiency and more than 20 percentage points lower than the national average.

Facing poor job prospects and a host of economic and social ills that often plague tribal communities, Native American students sometimes feel alienated and unimportant, Begay said.

One Native American student, when asked by Begay what he planned to do after high school, answered: “What does it matter, and why do you care?”

Response exceeds expectation

Adopted in 2011, Arizona’s education savings account was originally open only to students with special needs, later adding students attending the state’s worst rated (“D” or “F”) schools, those adopted from the foster care system and a few other specific criteria.

State legislators, in recognition of the lingering inequity of Native American children’s education, expanded eligibility for the specialized funding to children who live on reservations in 2015.

The response from Native American parents was immediate, Begay said. When selling the bill to colleagues, he said he expected 30 or 40 Native American families to apply. The legislation passed after the regular ESA enrollment period had closed and just a few months before eligible Native American children would be able to use their new benefits.

Despite that truncated window and minimal advertising, well over 100 families applied, a number that “far exceeded any expectation, even on my own part,” Begay said.

Of the 2,500 students using the program at the start of last school year, 150 qualified because they live on a reservation, according to the state Education Department.

Begay sees the ESAs as Indian education coming full circle: even though tribal leaders turned over responsibility for education to state and federal governments in treaties signed in the early 19th century, Native American parents now have a new and powerful tool to shape their children’s schooling.

Among the parents eager to wield that tool were Tamelia Boyd, the mother whose three children attended St. Michael Indian School when they were younger but then had to leave when the family could not get the financial assistance it needed.

Her son, Kaelen a junior, and freshman twins, Dale and Natelie, weren’t getting the grades their mother expected after they returned to public school. Other students’ behavior was sometimes an issue, and there were conflicts with teachers.

“I had to step in and I had to take action because I didn’t want them going through that for their high school years,” she said. “It was a little difficult at the beginning. They were mad at me for taking them away from their friends. After a couple of months, they understood why I had to do that.”

Another mother, who spoke on the condition that she not be named because she feared jeopardizing her daughters’ scholarships, also faced pushback from her girls when she decided to transfer them out of their Window Rock, Arizona public school.

Their grades also weren’t as high as they should have been, she said, and some of the 18- and 19-year-old boys at the school were making inappropriate advances toward her older daughter, who will start her junior year at St. Michael in the fall.

“What I’m trying to teach here at home, the school helps me with that, with structure and expectations,” the mother said.

AZ home to five of the worst BIE schools

The federal government no longer forces American Indian students into boarding schools or bans them from speaking tribal languages, a toxic philosophy known as “

kill the Indian and save the man,” but current efforts at education, through the Bureau of Indian Education, still fall woefully short.

The BIE spends plenty, over $15,000 per student, some $4,300 above the national average, and has little to show for it. The high school graduation rate in agency schools is 51 percent, as compared to 69 percent for Native American and Alaska Native students nationally, and 82 percent for all students. Test scores at BIE schools

aren’t any better.

Basic safety and bureaucratic functions have also proved to be a problem.

It seems that every few months, the Government Accountability Office, the primary federal watchdog, is out with a report detailing some new aspect of the agency’s failings.

One of the latest, released in March, found that more than a third of the agency’s 180 schools didn’t have a health or safety inspection in all of fiscal 2015. In those that had been inspected, flagrant violations, like missing fire extinguishers or boilers that leaked carbon monoxide, hadn’t been fixed. (The agency has promised it will hire more inspectors and inspect every school this year.)

The agency’s personnel are in disarray, too: director Charles “Monty” Roessel resigned in March after an

inspector general’s report found that he inappropriately tried to influence the hiring of both a romantic partner and a relative.

A promised agency-wide reorganization has yet to get necessary approval from congressional overseers. More money for school construction is slowly trickling in, though the agency is just now drafting a list of which schools need repairs — its first since 2004.

Five of the 10 BIE schools most in need of replacement are in Arizona.

They include the

Tonalea Day School, built in 1959, where floors buckle and doors jam and don’t close, letting water, dust, insects and rodents into the school. The

Blackwater School has so little space that counselors must meet with students outside to get some privacy, and there’s no gym, essential for children who face epidemic levels of obesity and diabetes but often can’t play outdoors because of the scorching heat. There’s still asbestos at the

Greasewood Springs School; classes had to be cancelled in November after dangerous tiles popped loose, creating an air safety hazard.

Given all of those colossal deficiencies, it’s hardly unexpected that parents are seeking a way out — particularly when one so easily exists for Native children in state-run public schools.

McCain sees the issue as inherently one of basic fairness. “I believe that parents should have a choice,” he said. “Why shouldn’t a person, an individual, who lives on an Indian reservation have that same opportunity?”

There are numerous hurdles standing between those families and that choice. First, staffers on the Hill have to work through some changes that the BIE, Arizona state officials, and others have requested to McCain’s bill.

They’re exploring giving the money to states up front, rather than requiring them to seek reimbursement from the federal government, for example. Other changes may include clarifying that money for sorely-needed BIE school construction can’t be included in ESAs, or requiring state legislatures to affirmatively opt into the program. The final bill also could be limited to an Arizona-only pilot program, staff said this spring.

Once the bill is in a more finalized form, McCain and his staff will have to build support among Senate colleagues. So far, it has no Senate co-sponsors, nor a companion version introduced in the House.

Republican Sen. John McCain introduced legislation in March to try and remedy the disparity that excludes BIE students. (Photo by Getty Images)

Outside of Congress, there is considerable opposition. The BIE, which is overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Interior Department, is firmly against it. Most of the schools the agency operates are very small, Lawrence Roberts, acting assistant secretary for Indian affairs at the Interior Department, said at an April Senate hearing.

Taking, say, four third-graders out of a class of 15 raises the per-pupil costs for those remaining students, he said.

“A lot of our schools are small schools, and [we] appreciate the goals that you’re trying to put forward, but the impacts on the students that are in BIE schools is concerning,” he said.

Agency leaders also have concerns about potentially having to take money back from the tribes that runs the schools, Roberts said. And, he said, because private schools don’t have to accept all students and don’t have to provide data to show how well students are performing, there’s no guarantee it would have a big impact for Native American kids.

“While it may help some students,” he said “it’s not going to provide a cure-all.”

Bureau of Indian Affairs and BIE officials did not respond to requests for additional comment.

The National Indian Education Association, the union representing teachers of American Indian students, officially hasn’t taken a stance, but testimony by the organization’s head reflected many of the same issues raised by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

“If BIE students leave to attend non-BIE schools, then those that remain will experience exacerbated educational disparities,” NIEA President Patricia Whitefoot said at the same hearing. Some costs, like transportation or housing, remain at a fixed level regardless of the number of students who attend BIE schools.

She said the group is concerned that Native American students won’t receive the culturally sensitive education that research has shown helps them succeed if they transfer to schools not run by tribal officials.

Sen. Jon Tester of Montana, the committee’s top Democrat, is also opposed.

McCain’s bill “takes critical funding away from tribes and BIE schools across the country to subsidize voucher programs in a small handful of states,” Tester’s staff said in an email. “[Tester] believes this bill will decrease the quality of public education on Indian reservations while costing taxpayers money.”

And although the bill has the backing of the Colorado Indian River Tribes (a small community in Arizona and California), and one Navajo leader, it doesn’t yet have the official blessing of the Navajo Nation government (the most populous American Indian tribe), or the National Congress of American Indians.

“I think this is the beginning of a fight…Yet, I also see an enormous response from Native Americans throughout my state that are totally dissatisfied with the quality of education their kids are getting from BIE schools." — Sen. John McCain

Overshadowing all of those impediments is the political fate of the bill’s champion, McCain, who is up for re-election this year. Fallout from GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump, in particular with Arizona’s large Hispanic population, has left McCain facing what is

likely to be the closest race since his first, to the U.S. House, in 1982.

McCain sees the bill introduction as just the start of the charge for change.

“I think this is the beginning of a fight…Yet, I also see an enormous response from Native Americans throughout my state that are totally dissatisfied with the quality of education their kids are getting from BIE schools,” he said.

McCain said he hopes to hold another hearing on the legislation in September, when Congress returns from its annual summer recess. Sen. John Barasso of Wyoming, the committee chairman, supports McCain’s proposal, but no further legislative steps are on the calendar, Barasso’s staff said in an email.

Begay, who is running for Congress to replace Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick, the Democrat challenging McCain, said Indian education for most D.C. politicians, is an “out of sight, out of mind” issue. There are federally recognized tribes in only 36 of the 50 states, and in some of those 36, the tribes are very small. There are BIE schools in even fewer states.

Representatives from states with large Native American populations, like Arizona or Oklahoma, are aware of the problems and work on solutions, but “it’s not going to be a national priority,” Begay said. “Some of the families and communities with the most need are not a part of that conversation.”

A boon for St. Michael

The ultimate goal of education savings accounts , advocates say, is not just to give children options right now, but also to create a broader educational “marketplace” that provides even more choices for the future — from additional seats at existing programs to entirely new schools, tutoring programs and other options.

And those alternatives are sorely needed, Begay said, “There is no such thing as school choice programs in many tribal communities.”

One of the few available is northeastern Arizona’s St. Michael Indian School.

The school was founded in 1902 and is, by most measures, excellent: 99 percent of its class graduates each year. The school offers Navajo language, arts and culture classes mixed in with traditional Catholic religion instruction and weekly Mass.

The ESA program has already helped expand enrollment, said Dot Teso, the school’s president. Of the 127 new students who enrolled in the 2015-16 year, 73 attended using education savings accounts. An additional 10 families wanted to enroll via an ESA but had to be turned away because the children attended BIE schools, she said.

Last school year was the first time all students (except BIE, of course) living on tribal lands were eligible for the funding. School officials had been accepting Native American students who qualified for other reasons but didn’t typically broadcast the funding’s availability.

One of those other qualifiers was attendance at a school rated D or F. That was definitely true of the public schools St. Michael students previously attended, Teso said, “but that’s a hard way to be a good neighbor, that you should advertise that you should come to us because everything around us is horrible.”

Moving forward, 80 to 90 percent of the new families enrolling at St. Michael are likely to be ESA recipients, she said.

The school will expand, both at its current building and possibly to additional campuses, but that growth will be slow, Teso said.

Current capacity is 650, and enrollment in the 2015-16 year was 389. Officials plan to grow to about 430 students next school year, and somewhere around 450 to 475 the year after that, she said.

There are limits to how quickly the school can expand enrollment. It’s difficult to attract teachers willing to work in such a remote location, for example. And despite the funding influx from the ESAs, there’s still a $2,500 to $3,000 per-pupil-deficit between St. Michael’s tuition and how much each student’s education actually costs.

“Expansion has to be really slow. We have to steady the ship, make sure our development is catching up with the demand, make sure we have the money and the infrastructure to take more students,” Teso added.

Teso said she’s grateful for the funding; officials wouldn’t even consider adding another building without the state dollars.

“We’ll be caught up within two years (between funding, supplies and staff) and I think a lot of other schools will be too,” she said.

The history – and future – of ESAs

Education savings accounts are among the newest school choice options, and one that has grown rapidly in recent years.

They’re more diverse than vouchers, which strictly use state funds to help parents pay for private school tuition, and different from tax-credit scholarships, which give tax breaks to businesses or individuals that contribute to nonprofits that then help with private school costs.

Education savings accounts can be used for a variety of purposes, depending on the state. In most places, parents can use them to cover private school tuition, tutoring services, home school curriculum, or therapies for students with special needs. Any funds not spent in K-12 can usually be saved for college.

In Arizona, the average annual award is $12,000; specific amounts depend on a student’s home school district and whether or not the child is eligible for special education services, according to state officials. Each state calculates the number differently, but in most cases it’s a set percentage of the state dollars that would be spent on a student’s education, sometimes increasing for students with special needs or fluctuating depending on family income.

The idea originated in Arizona, explained Jonathan Butcher, education director at the Goldwater Institute, a conservative and libertarian think tank.

The state Supreme Court in 2009 said that a state program that provided vouchers for students with special needs and those in foster care to attend private schools

violated the state constitution. Arizona has a

clause in its state constitution — as do most states — banning state funds from being spent “in aid of any church, or private or sectarian school, or any public service corporation.”

Advocates at Goldwater had envisioned the idea of education savings accounts several years before they were formally proposed, but held off on promoting them in deference to the burgeoning voucher movement, Butcher said.

Then Arizona became the perfect test case.

“There were two things going on,” he said. “There was a voucher bill that was ruled unconstitutional, and we wanted to help those kids that were going to lose their school vouchers, and there was this very ambitious embarking on a whole new view of how to provide parental choice in education.”

The state legislature passed a bill in 2011 to provide education savings accounts — in Arizona, they’re called Empowerment Scholarship Accounts — to children with special needs. The new program was again challenged in court, but justices said this one passed state constitutional muster because parents could direct the public dollars to a number of educational options, not just private schools.

In the intervening years, legislators have expanded eligibility to the children of parents in the military, children who have been adopted from the state foster care system, those attending schools rated “D” or “F” and, most recently, children who live on Native American reservations. There’s a bill before the legislature to make the program universal.

And, just as the programs have spread to encompass more categories of children in Arizona, they’ve spread to other states, too.

Florida, Mississippi and Tennessee offer ESAs for students with special needs. Nevada in 2015 passed the first universal ESA; it’s currently in the midst of legal challenges.

Bills have been introduced in scores of other states — legislators in Virginia, for instance, passed ESAs for special needs children earlier this year, but Gov. Terry McAuliffe vetoed it. And more state lawmakers are likely to consider them again when they come back into session in early 2017. There could be bills introduced in Oklahoma, Texas, Missouri, West Virginia, Georgia and Delaware, advocates said.

The appeal of the programs is two-fold: wide choice options for parents, and, in many places, a way around religious prohibitions.

“The constitutional concern is always a question in any state, but that’s not really what people are finding the most appealing,” said Leslie Hiner, vice president of education programs at the Friedman Foundation. “What they find most appealing is the opportunity that it offers is so broad.”

A child from a struggling public school who transitions to a more rigorous private option may need extra tutoring, for example — something that’s available with an ESA but not a traditional voucher, Hiner pointed out. And the educational needs of all students, but in particular those in special education, may change over the course of their school careers, she said.

The program isn’t a silver bullet, of course.

For one, state governments haven’t yet figured out the best way to balance getting money to parents quickly while preventing fraud. In Arizona, for example, state officials indicted a woman who allegedly used ESA funds to buy a flat-screen television and for family planning services,

The Arizona Republic reported. There’s also the question of how many students should be eligible, and how large an allocation should be provided.

There’s been no research on academic outcomes under ESAs because they’re so new, but research on more traditional, limited voucher programs is mixed.

A

December 2015 study of Louisiana’s program found that participating students had substantially reduced test scores across subjects, something researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research said might be due in part to the program’s participation of “low-quality schools.” A

study of Washington, D.C.’s voucher program found very high parent satisfaction and a much higher high school graduation rate among voucher recipients, but no significant improvement in test scores.

In addition to the constitutional concerns with funding religious institutions, opponents in state legislatures also charge that the programs force students out of public school, or take money away from often underfunded public schools.

“This bill raises constitutional questions, diverts funds from public schools, and creates an unfair system,” McAuliffe, the Virginia governor, said

in a written statement when he vetoed his state’s ESA bill. “Our goal is to support and improve public education across the Commonwealth for all students, not to codify inequality.”

The one criticism that advocates dismiss out of hand is that parents, particularly low-income parents or those who didn’t have great educations themselves, can’t make appropriate schooling choices for their children — reasoning Hiner called “wrong and bigoted.”

“This is a story about parents who need a decent education for their kids and giving them the opportunity to find it,” Hiner said. “That is what school choice is in a nutshell, and it works.”

(The Dick and Betsy DeVos Family Foundation is a funder of The 74. The 74’s Editor-in-Chief Campbell Brown sits on the board of the American Federation for Children.)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)