The Trump administration’s fundamentalism about school choice is problematic in its core premise, which is something like: If parents are offered a variety of schools, they’ll choose a good one. And if it turns out not to be good, they’ll leave for a better match.

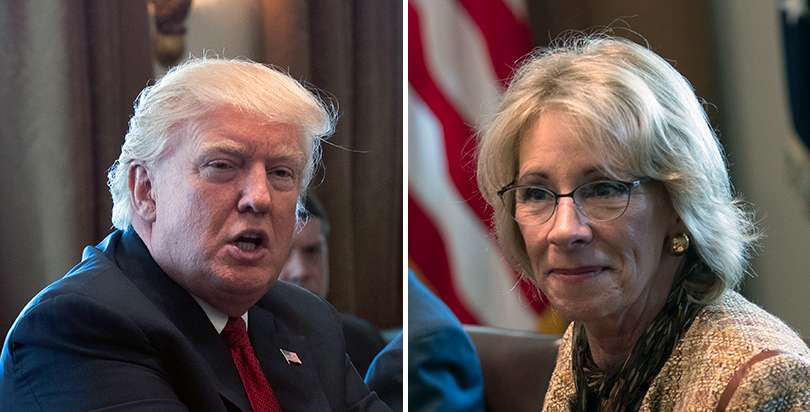

“We have the opportunity to get Washington and the federal bureaucracy out of the way so parents can make the right choices for their kids,” Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos said earlier this year.

“We must offer the widest number of quality options to every family and every child,” she said. “Parents know — or can figure out — what learning environment is best for their child, and we must give them the right to choose where that may be.”

Unfortunately, it’s doubtful whether this is true for almost any parent.

Given the many tasks we expect schools to perform — furnishing childcare and safe diversions, building knowledge and academic ability, improving non-cognitive skills, providing friends and guiding socialization, building character and citizenship — it’s unlikely that most adults with advanced degrees would be able to truly assess how effective and well-suited a school is for their children on the basis of one or two visits. Any more than they actually know how good their cardiologist is.

And while some parents — typically more affluent ones — spend time researching options and mobilizing their social networks for information, most do not. In choosing schools, children from low-income homes and immigrants often rely on the haphazard advice of siblings and friends or they do it alone.

“Low-income Latin American parents interviewed did not view oversight of or even participation in their child’s high school decisions as part of their parental duties,” writes sociologist Carolyn Sattin-Bajaj, who spent 18 months interviewing 46 families in New York City for her 2014 book Unaccompanied Minors: Immigrant Youth, School Choice, and the Pursuit of Equity.

“The most striking pattern in Latin American immigrant parents’ responses was the pervasive reference made to the belief that ‘there are no bad schools, only the students inside the schools are bad’… [One father said], ‘there are good teachers and bad teachers, but in my opinion it is up to the kids.’ ”

African-American and third-generation immigrant parents tended to be more engaged than newer immigrants, Sattin-Bajaj says, but their information may be limited to calling a school “bad” because an older sibling dropped out. “The majority of these students relayed an overall sense of being singularly responsible for their own choices,” she writes.

Friends can be helpful but also copy one another’s choices, good or bad: “My friends influenced me ’cause I don’t like being the only one that goes to a school,” said one girl. Same with siblings: “My sisters … they did it,” another girl said of her application.

A separate study of five years of high school admissions data in New York City, where students can rank up to 12 schools anywhere in the city (charters aren’t included), found that low-achieving students were matched to lower-performing schools more often than other students. The authors found that they were just as likely to get their first choice as higher-achieving students but the schools they picked were “less selective, lower-performing, and more disadvantaged.”

The authors attributed the discrepancy “at least in part” to the fact that students prefer to be closer to home (the importance of proximity in school selection decisions is well established) and “lower-achieving students are highly concentrated in poor neighborhoods, where options may be more limited.” In other words, students may often choose to go to a struggling nearby school then a better one farther away.

This may partly explain why the No Child Left Behind program that allowed transfers out of struggling schools was utilized by only about 2 percent of families. And why there are always families who fight to keep schools open that have been failing for years.

And it’s why a remark by a DeVos spokesperson last week — “the ultimate accountability for schools is whether or not parents choose to send their children there” — should be seen as an attack on the idea that school quality matters. It’s fake accountability.

The Education Department has a proof-of-concept problem. The unfettered marketplace it envisions may create great possibilities for children whose parents can master it, but so does every other system.

What it doesn’t do is reflect how most families select schools (for suboptimal practices at earlier grades, see this collection of essays), nor does it begin to contemplate why more choices would change that — how it would overcome cultural, ethnic, educational, class, and value obstacles in order to provide the information poor parents badly need.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)