Can Right Answers Be Wrong? Latest Clash Over ‘White Supremacy Culture’ Unfolds in Unlikely Arena: Math Class

By Linda Jacobson | June 21, 2021

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

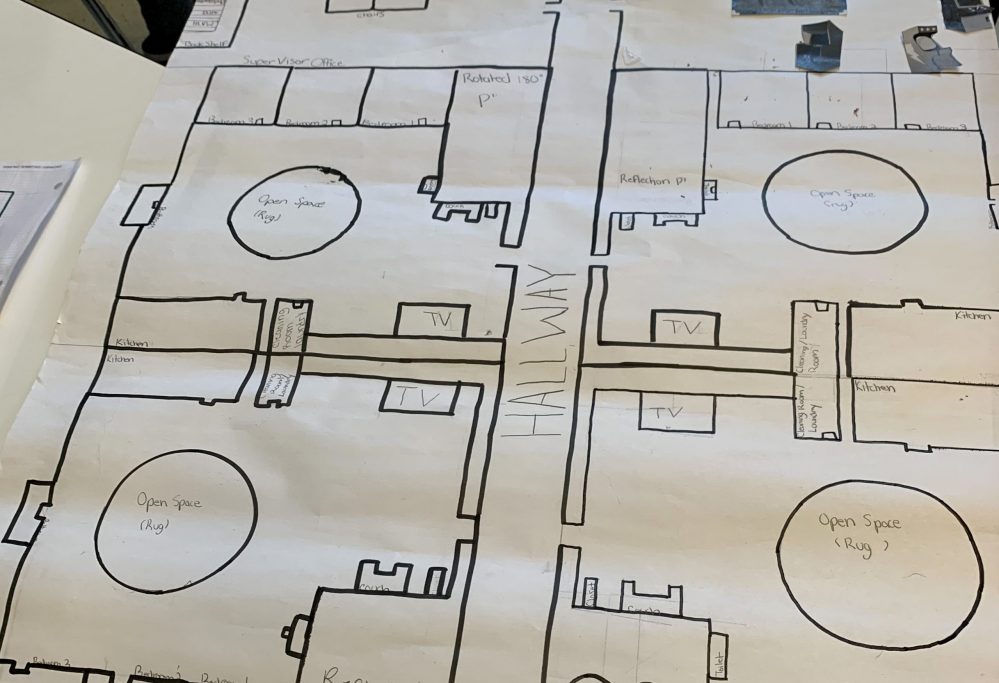

To learn the geometric concept of transformations this year, Crystal Watson’s eighth-graders drew up blueprints of apartments. As they worked, she asked them to imagine designing affordable housing for Black and Hispanic families like theirs in Cincinnati who have been priced out of their neighborhoods.

But when she had them add a hallway down the middle of their floor plans, with apartments on either side, some struggled with the idea of reflection — flipping a figure to create a mirror image.

“There are still kids who mix up their x and y axis,” said Watson, who teaches at Hartwell School.

At that point, she pulled students aside individually to explain the difference and offered tips for remembering. Her strategy — connecting math to socio-economic issues in the community and letting students proceed even if they haven’t mastered the skills — is captured in a workbook that gives teachers steps for “dismantling racism” in math instruction.

But the book’s claim that a focus on producing the right answer promotes “white supremacy culture” alarmed some who question how inaccuracy in math could benefit students. And, partly in response to the controversy, California state board members recently recommended against incorporating the resource into a redesign of the state’s math program.

While history and literature seem like obvious battlegrounds for schools to address the effects of racial discrimination, some might question whether math — where achievement depends on precise calculations — is the appropriate venue for such fights. Those devoted to greater equity say the middle grades are a period when many Black and Hispanic students begin to turn off of math, only to continue struggling through high school. But the suggestion that answers to math problems are subjective became easy fodder for culture war conservatives.

“Math enjoyed this notion that it was somehow above the influence of the cultural and political issues of our time,” said Rachel Ruffalo, the director of educator engagement at The Education Trust-West, the Oakland-based advocacy group that created the workbook.

Now, that is changing. The workbook is part of the organization’s larger math equity project — one that seeks to address persistent racial disparities in achievement. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the $1 million initiative last spring as part of a grant program focused on making algebra more accessible to students of color, partly in response to learning disruptions caused by the pandemic. Districts in Georgia, Ohio and California are among those using the workbook in teacher training.

Conservative Fox News lampooned, sometimes out of context, a handful of the book’s ideas — for example, the notion that key teaching practices such as requiring students to show their work and complete assignments individually are based in racism. The article appeared in mid-February after the Oregon Department of Education invited teachers to a training featuring the book. The Fox piece sparked coverage in other outlets and reactions from columnists, most of whom neglected to mention that the authors later say, “Of course, most math problems have correct answers.”

Erec Smith, a professor of rhetoric and composition at York College of Pennsylvania and co-founder of Free Black Thought, is among those who accuse the book’s authors of their own form of bigotry.

“The workbook’s ultimate message is clear: Black kids are bad at math, so why don’t we just excuse them from really learning it,” said Smith, who is Black.

Even leaders of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics have reservations about the guide — though their reasons differ.

“Are we building bridges or throwing grenades?” asked David Barnes, associate executive director of the council. “When you get to page two and what’s bolded is ‘dismantling white supremacy,’ there are some people that cannot read past that.”

Other groups came to Oregon’s defense, offering positive reactions to the book and its broader effort to make math more culturally relevant for students of color.

“You and I were taught that everything happened in Greece,” said Kristopher Childs, director of Student Achievement Partners, a nonprofit focusing on academic success for historically underserved students. “Every culture and civilization contributed to mathematics. Students need to know that.”

The authors, for example, prompt teachers to have students explore the Egyptian and Babylonian roots of the Pythagorean Theorem, before Pythagoras identified it in Greece during the 6th century B.C.

The guide draws inspiration from another document titled “Dismantling Racism,” which includes what some scholars on race argue are characteristics of “white supremacy culture” — ideals such as perfectionism, individualism and a sense of urgency they say allowed early American colonists to dominate over African slaves and Native Americans.

‘Room for creativity’

Samuel Rhodes, an assistant professor of elementary math education at Georgia Southern University, said focusing only on the right answer can at times be counterproductive. In a course last year for future K-8 teachers, he called on a student who gave a wrong answer to a problem.

He said he could have done what he’s observed in countless public school classrooms — go on to the next student until someone answered correctly, or repeat the steps.

But with that strategy, a “student … just immediately shuts down,” Rhodes said. “Now they have to ignore everything they were thinking with the goal of trying to understand how the other students did it.”

Instead, he asked the student how she arrived at that answer and learned she had a “creative, brilliant process” for finding the solution, but got derailed by a small computation mistake.

“There’s no room for creativity when there is a fixation on the answer,” he said.

But knowing whether a student is “wildly wrong” or “off by just a hair” takes deep expertise in math — something teachers, especially those at the elementary level — don’t always have, said Jay Wamsted, a longtime Atlanta math teacher working in high schools serving predominantly Black and HIspanic students.

He added, “It’s not obvious to the layperson why ‘the right answer’ isn’t always preferable and the workbook needs to be clear about why that is.”

While the workbook discourages teachers from asking students to “’show their work’ in … prescribed ways,” it does recommend that students have multiple options for demonstrating what they understand.

That’s a shift Lisa Owens, another Cincinnati math teacher, is still trying to make.

“For me, that was letting go of control. For a lot of teachers, that is where the issue is,” said Owens. But she said she’s learned to spot shallow attempts at cultural relevance. “You can’t just put an ethnic name into a word problem.”

Beginning her career in a Chicago suburb, she said she “was raised that you don’t see color.” But now Owens, who is white, teaches at Roberts Academy, which serves a predominantly Black and Hispanic population. She helped start a school equity coalition and opposed the school’s former practice of tracking fourth graders into low and high classes based on math scores.

She recognizes the hurdles involved in meeting the guide’s definition of an “antiracist math educator.” Allowing students to arrive at mistakes on their own can take up valuable class time, and a lot of teachers, she said, still take a “tough love” approach and question whether such methods would improve test scores. According to state data, less than 10 percent of the eighth graders in the school score proficient in math.

‘The role of education’

Teaching practices like those in the workbook have been part of the San Francisco Unified School District’s shift in math instruction since 2014. That’s when the district stopped separating students into basic or Algebra I classes in middle school — a controversial policy that California is now considering statewide. The state will continue to collect public comments over the summer, and the state board will make a final decision in November. Advocates for gifted students are against the proposed changes.

So far, administrators using the workbook have had a receptive audience of educators committed to “social justice math.” But when they try to spread those ideas among colleagues at their schools, they often face resistance.

“Challenging the status quo is not easy for a lot of teachers,” said Bernadette Andres-Salgarino, math coordinator for the Santa Clara County Office of Education in California.

The guide caused enough of a storm in California that members of the state board advised its Instructional Quality Commission, which is drafting the new math “framework,” to remove references to it.

While Barnes, with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, thought the guide used “words that immediately divide,” he appreciates the intent behind it — an effort to make math more accessible for students of color and give them a strong foundation when they enter high school.

It complements, he said, the push in California and Oregon to de-track math by keeping students in the same courses at least through the eighth grade. Virginia is considering similar changes.

Data shows less than 20 percent of Black students take Algebra 1 by eighth grade, compared to 67 percent of Asian students and 45 percent of white students. And even if they take higher-level math in middle school, Black students are less likely than white and Asian students to stay on an accelerated track in high school.

The pandemic has set students of color even further behind. Winter assessment data from testing provider Renaissance showed that while all students performed below pre-pandemic levels in math, the decline was greatest among Black and Hispanic students. And on a national scale, the gap in math between Black and white eighth-graders hasn’t budged in years.

Williamson Evers, a former U.S. Department of Education official during the second Bush administration and a senior fellow at the conservative Independent Institute, suggested the social justice approach to math will put U.S. students further behind those in other countries.

“Our kids are going to be competing in a world with kids that have this in their heads. They’re doing better. They have the material under their belt,” he said during a recent podcast. His commentary in the Wall Street Journal ran before California state board members turned their back on the workbook.

Josie McSpadden, a spokeswoman at the Gates Foundation, defended the project.

“At times, research has shown that racial bias and student mindsets can affect student academic achievement,” she said, adding the workbook, “highlights a critical discussion — how students arrive at answers and demonstrate their understanding and conceptual grasp of important math concepts.”

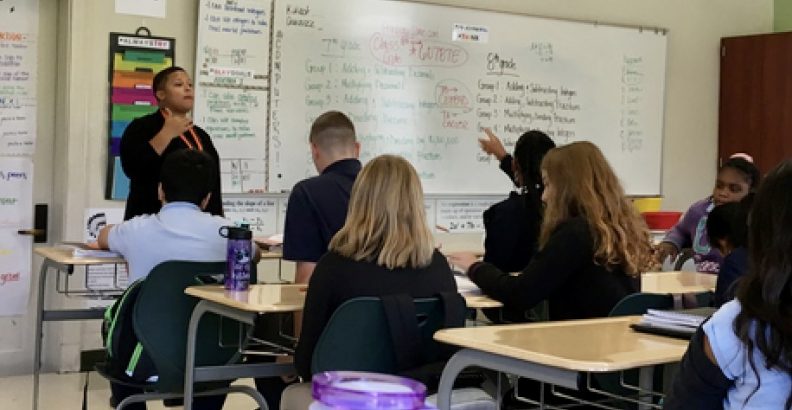

This fall in Cincinnati, math teachers throughout the district will walk through the practices recommended in the guide. Watson — who plays clean versions of rap songs in her class when students finish an assessment — said math is usually “so cut and dried.” The resource gives teachers ways to incorporate students’ opinions and family stories into her lessons.

“I don’t have to be an anti-racism and anti-bias guru,” she said, “to pick this up and do what’s good for kids.”

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to The Education Trust-West and The 74.

Lead Art: A math teacher works with a student at Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School in San Francisco. The district is among those working to address racial disparities in math achievement. (Lea Suzuki / The San Francisco Chronicle / Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter