Can Baby Bonds Deliver on Promise to Close Rhode Island’s Wealth Gap?

General Treasurer James Diossa says trust fund set up for children on Medicaid at birth can have big economic payoff later.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Trust fund babies tend to get a bad rap. But Rhode Island General Treasurer James Diossa wants more of them — 4,600 a year more, to be exact.

That number is based on estimates included in Diossa’s 2024 legislative package unveiled at the State House on Jan. 24.

These would not be your stereotypical, spoiled young people whose family fortune affords them seemingly unearned privileges. Instead, Diossa’s baby bond proposal aims to carve out a path to wealth for low-income Rhode Islanders whose circumstances make it difficult to pay for college, a house, or even a car.

“There is a long history of inequities in Rhode Island and in this country, and a proposal like this could change that dynamic,” Paige Clausius-Parks, executive director of Rhode Island KIDS COUNT said in an interview.

“If we want our employment rate to be good, if we want our school systems to be good, if we want to be able to live in safe communities, everyone needs to be able to meet their basic needs.”

A 2021 report by KIDS COUNT laid bare the divide between Rhode Island’s wealthiest and lowest income children, the latter of whom are disproportionately children of color. Black and Hispanic children are seven times more likely to grow up in poverty as their white peers and half as many come from families that own homes, according to the report.

Diossa’s Rhode Island Baby Bond Trust Act aims to narrow that chasm, creating a $3,000 trust for each baby born into a family on public health insurance. The money would be managed and invested into stocks and bonds by Diossa’s office for the first 18 years of a child’s life, with the intent to grow the deposit into a $12,000-$15,000 nest egg over an 18-year period, according to Diossa’s office. Once the child turns 18, they would be able to tap into the money to cover costs associated with higher education or vocational training; buying a home; starting a Rhode Island-based business; or buying a vehicle.

Big return on investment

It’s a visionary idea that requires a long-term view to understand the payout – not only for the beneficiaries of the bonds, but for the economy as a whole through home sales, business growth and a more educated workforce. Diossa’s office estimated the $13.9 million cost to cover an initial, 4,600 group of Medicaid babies with $3,000 apiece investments would generate $50 million in economic output.

The return on investment sounds appealing, but convincing lawmakers on Smith Hill, already facing tough choices on education and health care funding, will not be an easy feat, Diossa acknowledged.

“In the short-term, we’re not going to see any gains or make a difference,” Diossa said. “I won’t be treasurer in 18 years, but I know there will be a cohort of kids who qualify for this program who will be able to put a down payment on a home, or start a business, or continue an education.”

Helping his case: pressure to keep up with surrounding states where a wonky policy idea proposed in a 2010 paper by a pair of economists is quickly gaining traction.

Connecticut became the first state in the nation to implement a baby bond program that passed the state legislature in 2021, though political headwinds delayed its implementation until July 2023. A dozen other states have since introduced legislation or created task forces to study the idea, including Massachusetts, where a task force released a report of broad-brush recommendations for implementation in December. Vermont legislators introduced a baby bond bill earlier this month based on a proposal from its state treasurer.

In Rhode Island, the Rhode Island Baby Bond Trust Act is awaiting a legislative sponsor, along with the not-so-small detail of a funding source. Diossa said his office was reviewing several internal opportunities to pay for the program, but declined to share which options were under consideration. A funding source will be identified once the legislation is introduced within the next two weeks, he said.

Gov. Dan McKee remained noncommittal, with Olivia DaRocha, a spokesperson for his office, responding via email that the governor would review the legislation when it is introduced.

A February 2023 paper by the Urban Institute stressed the importance of carving out a sustainable, long-term funding source not subject to the changing whims of a political body. Just ask DC, where the City Council approved a four-year funding plan for a baby bond program in 2021, only to have Mayor Muriel Bowser remove the funding in her fiscal 2024 budget (though it was then restored amid protests from officials and community members).

Connecticut’s baby bond program originally intended to rely on bonding to fund the initial 12 years, but the funding source was later shifted to draw from a reserve fund set aside during a prior restructuring of teacher pension debt. The $390 million allocation intends to cover 12 years of $3,200-apiece bonds for babies born into Connecticut families on the state Medicaid program. By the time the children turn 18, the deposit is expected to hit anywhere from $11,000 to $24,000.

Connecticut launch delayed two years

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and Treasurer Erick Russell gave the first update on the newly launched program on Jan. 17, sharing that 7,800 babies born across the state since July 1, 2023, were automatically enrolled. Demographic data on the trust beneficiaries to-date is also not available, according to Russell.

While Russell described the initial rollout as fairly smooth, the path to implementation was paved with obstacles. Even after former Connecticut Treasurer Shawn Wooden won support from lawmakers on his baby bond program in 2021, opposition from Lamont’s office forced a two-year delay, according to news reports.

Russell, who was elected in 2022 after the legislation passed, acknowledged the political tensions hovering over the program.

“It’s really difficult and takes a lot of political courage to look at making a long-term investment like this,” Russell said in an interview. “I won’t be in office, and most of the people who supported it likely won’t be in their positions by the time the benefit is paid out.”

Also a long way on the horizon – the research analyzing whether baby bonds programs in Connecticut, or maybe Rhode Island, achieve their intended goals.

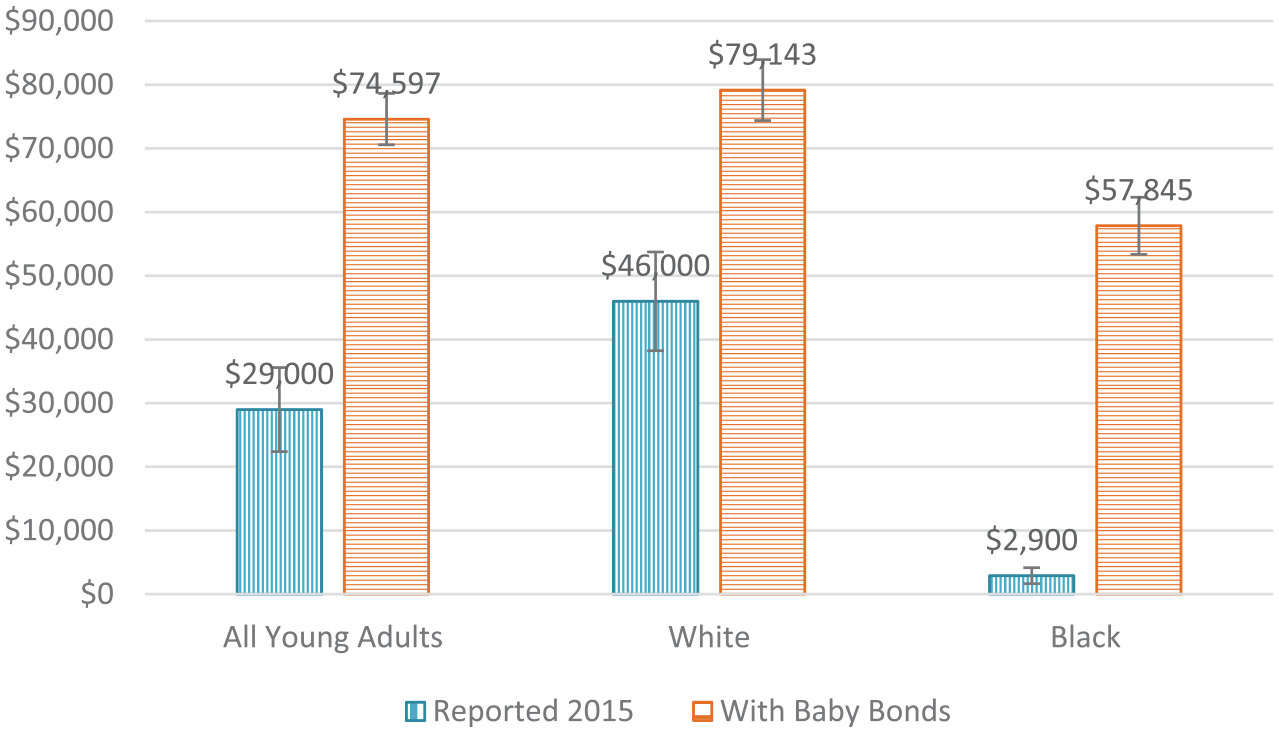

A 2020 paper simulating the effects of a national baby bond program found that it could improve average net worth while substantially reducing the racial wealth gap. Where White Americans held 16 times as much wealth as their Black counterparts in 2015 (based on data referenced in the paper), the gap would shrink to just 1.4 times under a baby bond program.

How baby bonds could close the racial wealth gap

The need for data

There’s no real-world data yet to prove the effects. While the Connecticut treasurer’s office is having initial conversations with philanthropic and research groups about how to track and measure outcomes for its initial crop of trust fund babies, that’s not the immediate focus given the 18 years before any data can even be collected.

More immediately, Russell’s office is focused on partnering with hospitals and community groups to make sure Medicaid families know about the trusts being set up for their babies, and monitoring the return on investment of the initial investment.

There are signs of progress that can be tracked even before the 18-year wait when trustees can dip into the money is up, according to Darrick Hamilton, an economist who co-authored the 2010 paper that popularized the idea of baby bonds. Hamilton is also a professor and founding director of the Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy at The New School in New York.

“Black and Latino communities are used to a punitive relationship with the government,” Hamilton said. ‘If you start with this foundation, you build trust between the state and the people. It’s an opportunity to engage with families from the cradle all the way through adulthood.”

Diossa envisions coupling the program with financial literacy for the families and children who will benefit from the trusts, along with other wraparound services.

And while an untouchable investment won’t pay their monthly heating bills or grocery costs, the nest egg can offer both emotional and tangible benefits before the money actually becomes available.

“Just imagine if you’re in a family who doesn’t have the wealth or the income levels to really provide a comfortable lifestyle, and are receiving annual statements showing a fund growing year-to-year, and know in 18 years you will have a wealth-building mechanism,” Diossa said. “That changes the whole dynamic, the way you look at the future.”

Like other states, Diossa’s proposal would enlist a third-party vendor to manage distribution of deposits once trustees are of age, with checks written not to the beneficiaries themselves, but to the college, bank or mortgage company where they want to invest their money. A portion of the investments would cover the fees for that service, meaning there’s virtually no administration cost for the state.

Other state programs don’t allow car purchases

One distinction separating Rhode Island from other states that have studied, or started, baby bond programs: letting trustees use the money to buy a car. While home ownership, higher education or business investment are popular options heralded as appreciating assets, cars are just the opposite, losing value over time.

However, in a transit-limited state like Rhode Island, lack of transportation in turn inhibits pursuit of education, or work, Clausius-Parks said.

“We have a lot of great scholarship programs like Rhode Island Promise and the Hope Scholarship, but it doesn’t cover certain things like transportation to getting to class,” she said.

Hamilton also stressed the importance of tailoring state-based programs to their environments, as well as budget constraints. His initial policy imagined a federal baby bond program in which all families, regardless of income, would have trusts, though the amount depended on their wealth. State-level restrictions on balancing a budget make the cost of universal baby bonds unrealistic at the state level, although a federal child savings account program remains on the table based on legislation introduced last year by Rep. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey.

Despite the funding difficulties and political battles required, Hamilton expects to see more states take up or advance the baby bond program this year as calls to close the wealth gap grows to a battle cry.

“The American Dream has been rhetorical, for the most part, for many families,” Hamilton said. “If we want to make it authentic, we need to see capital.”

Rhode Island Current is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Rhode Island Current maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Janine L. Weisman for questions: [email protected]. Follow Rhode Island Current on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)