California Revises How State’s ‘School Dashboard’ Is Calculated, Moves Several Districts Out of Lowest-Performing Category

This article was produced in partnership with LA School Report.

California parents who want to know how schools are performing will now have to look deeper into the new California School Dashboard to figure it out.

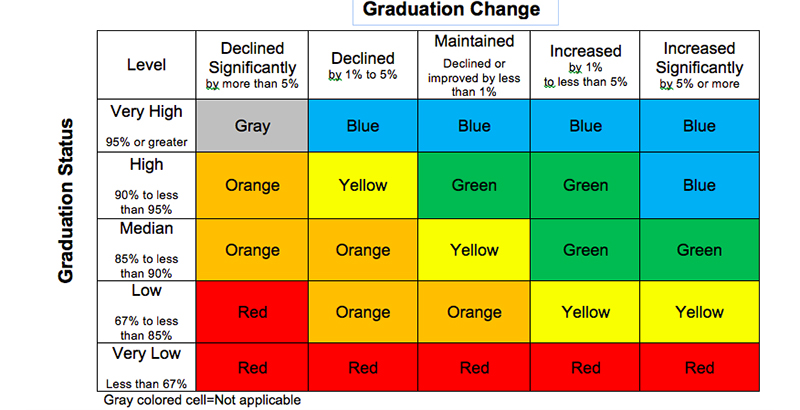

The dashboard, which was rolled out this spring as the state’s new way to assess schools and school districts, is a collection of color-coded boxes rating various aspects of schools. Red is the lowest rating and indicates the lowest-performing schools and school districts.

On Wednesday, the state Board of Education decided to move dozens of schools and districts out of the red for one reason — they had too many.

The problem stemmed from students’ performance on state tests this spring, which was below what state officials expected. English language arts scores declined, and math scores were basically the same as last year — in fact, the improvement was so minuscule that for the first time the results were released in decimal points.

So the state board decided to “tweak” the numbers so more schools would show up in the orange category instead of red. If they didn’t, the number of schools in the red category would almost double.

The State Department of Education’s staff explained during the meeting that the current number of districts — 119 — in the red category based on math scores would have risen to 231. With the adjustment, that number drops to 89.

The board members called the tweak a “technical” matter and voted unanimously to approve it. But education advocates found the move “troubling,” saying it sends “the wrong message” to districts and looked like the state was lowering the bar.

“Let’s think of this as when you go to the doctor because you feel sick and the doctor tells you that you’re fine and to go home, but you feel terribly sick. That’s how the state is making look OK low-performing school districts,” said Seth Litt, executive director of Parent Revolution, a Los Angeles–based nonprofit organization that empowers parents striving to improve their children’s education.

He said parents will now have to look harder at the dashboard’s grid of colored boxes to understand what needs improvement in their schools, and in what areas the schools need assistance or resources.

“Parents have the right to know what schools they don’t want to send their kids to, and the state is just now making it harder for them to get clear information on low-performing schools. They want improvement for their kids in school, but then they see this dashboard and they will see everything is OK. They won’t have clearer information on what can be done to improve the school,” he said.

“The details really matter,” Ryan Smith, executive director of Education Trust–West, said via email shortly after the board’s approval. “Changing the color of a cell may seem like a technical issue, but it also communicates expectations for how schools should be doing. We want to make sure the state is maintaining a high bar for student achievement, and that our dashboard is giving parents and educators honest information on how they are faring.”

Auri Muralles, whose seventh-grader attends New Designs Charter School in Los Angeles, said she feels disappointed that the Board of Education is making it more difficult for parents like her to have a report card on schools they can understand.

“Years ago, when my son attended 20th Street Elementary, he couldn’t read at his grade level, and still the school said he had a 4.0 GPA, and as his mother I knew that couldn’t be true. Now they are helping bad schools look like they’re not so bad by changing the scores, so we parents don’t realize how bad they are. That makes me feel angry,” said Muralles, who is a member of Parent Revolution.

“Why do the state and the district not want us to know the truth about our kids’ schools? We deserve to know how they are performing.”

Another problem with moving more schools out of the red category is that they won’t be eligible for extra help that low-performing schools get from counties. That could have been a reason that motivated the state’s decision, Litt said.

The kind of support provided by the county offices varies, but it won’t include more money, said Samantha Tran, Children Now’s education policy director.

“Most likely districts get assistance in assessing a factor in the community that is affecting the school’s performance or for guidance on how to make adjustments to their LCAP plan for the following school year,” she said. “We provided the board with a letter about what we believe the system of support should look like, but there’s nothing set yet; it’s still being defined.”

Tran added, “They had estimated a different amount of districts identified in that level, and even with this new shift, there will still be more in the red than what they expected. But that doesn’t mean that the ones out of the category can’t ask for support from their local county office of education. They still can, but they don’t have to at this point.”

Tran spoke at Wednesday’s public meeting on behalf of Children Now, a nonprofit advocacy organization that was part of a coalition that had sent a letter to the state board before the meeting asking for “greater transparency” in the process of changing the dashboard.

“The proposed changes in the academic indicator accountability measure are significant; yet, they are being brought to the board at the last minute and were made behind closed doors, without any public input,” the letter states.

Tran called the changes “pretty significant” and suggested that instead of relying only on the dashboard’s overall color coding, parents need to take a deeper look into each category: suspensions, English learner progress, and graduation rates in what is called the 5 by 5 grid.

“For example, your school can be shown in the yellow category, but what does that mean? Does it mean that school is doing OK but had a big drop in one of the categories? Or does it mean that it’s not OK but is stable and has been showing some growth? We need to look into all that,” she said.

During the meeting, board member Feliza Ortiz-Licon expressed concern. “Students who exceed [academically] will continue to exceed, and the ones that underperform will continue to underperform, and for those not receiving the assistance they need will only linger on underperformance. Makes me nervous that we may come back to this same conversation next year.”

Board member Ilene Straus said it is a “learning process” and that coming back to the same conversation next year is part of improving the dashboard.

Another board member, Bruce Holaday, said he was hopeful that this change in the dashboard could be explained to the public.

“This needs to be explained to parents, communities, and all constituents. It’s critical that they understand it.”

Wednesday’s decision only cemented in Muralles’s mind her belief that school districts and the state aren’t doing what they’re supposed to be doing to improve the schools in her neighborhood. “If they would do what they have to do to improve public schools, I wouldn’t have to take my son to a charter school away from home, or pay for a Catholic private school for my granddaughter for her to have a good education.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)