Buttigieg Was ‘Under the Illusion’ That South Bend’s Schools Are Integrated. But Despite a Decades-Long Struggle (and Federal Court Order), Stark Racial Divisions Persist

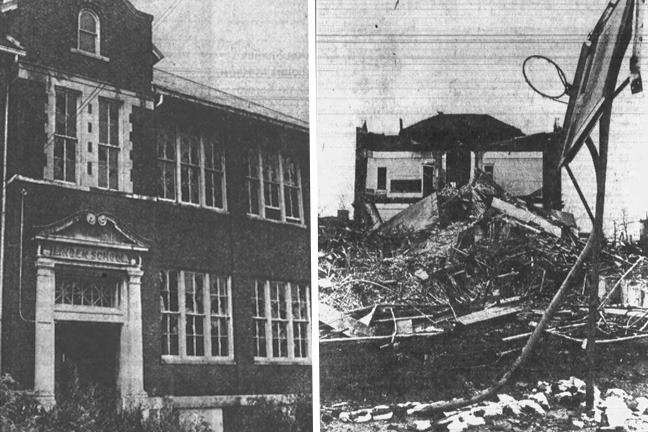

It was just before Christmas break, 1966, when a classroom ceiling at South Bend’s Linden School came crashing to the ground.

Nearly every child at the school was black, and neighborhood families hoped that shuttering the dilapidated building from the 1890s would allow students to integrate with their white peers at better-performing, more modern schools. The district had other ideas. Before the roof fell in, it sought to rebuild the elementary school campus at the same location. Though children in the classroom evacuated safely — seconds before rubble pummeled their desks — the ordeal reinvigorated a campaign to shut down the elementary school for good. In a lawsuit filed earlier that year, the NAACP had maintained that efforts to replace the building were motivated by a desire to maintain racial segregation in city schools.

The fight over Linden marked the beginning of a decades-long struggle to integrate the small Indiana city’s public schools. Following a federal consent decree in 1980, the South Bend Community School Corporation adopted a plan that school leaders said at the time would desegregate the city’s campuses “now and theoretically forever.” But the order remains in place to this day, as local activists continue to fight over disparities in student discipline and access to challenging academic programs.

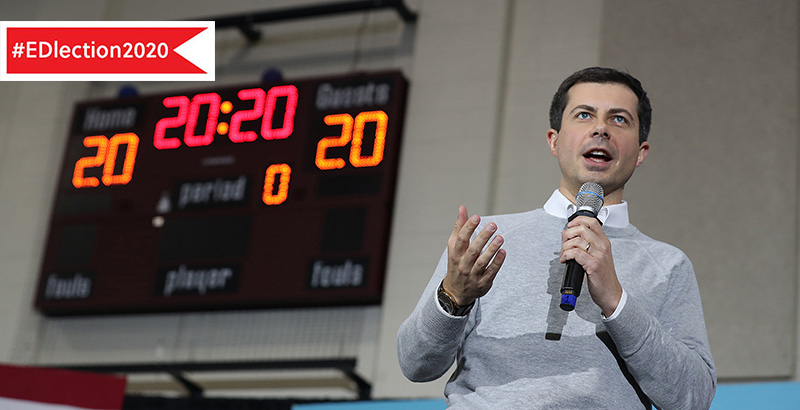

The Linden ceiling fell nearly 16 years before Pete Buttigieg, future South Bend mayor and Democratic presidential contender, was born. But controversy over the city’s desegregation efforts burst into the national spotlight during a recent campaign stop in North Carolina. “I have to confess that I was slow to realize — I worked for years under the illusion that our schools in my city were integrated because they had to be because of a court order,” said the mayor, whose last day in office was Jan. 1. While the comments underscored some of the candidate’s problems connecting with black Americans, they also highlight a reality that will face whoever is elected president in 2020: More than 65 years after the Supreme Court ruled school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education, many campuses across the country remain starkly divided by race.

Shortly after he made the comments, Buttigieg released a comprehensive education plan that seeks to address school segregation nationwide. His campaign didn’t respond to requests for comment on this story.

In South Bend, where the mayor has no control over school policy, the comments struck many as tone-deaf.

“It’s a little disturbing” that Buttigieg wasn’t aware of persistent segregation in South Bend schools while serving as mayor, said Trina Robinson, who previously led the NAACP’s local chapter and is now president of Community Action for Education. After years of forced busing, the city’s current desegregation plan utilizes a network of magnet schools to entice voluntary integration and school zones to combat segregated housing patterns. “You’ve got to correct something at home before you can do it on a national level.”

This school year, five of South Bend’s 30 schools — two high schools and three elementary schools — have student enrollments that fall outside the federal desegregation order’s compliance threshold.

“It’s not a hidden secret,” Robinson said.

The 15 percent rule

Decades before a presidential election campaign thrust South Bend into the national spotlight, the epicenter of the city’s fight over segregation was a single school.

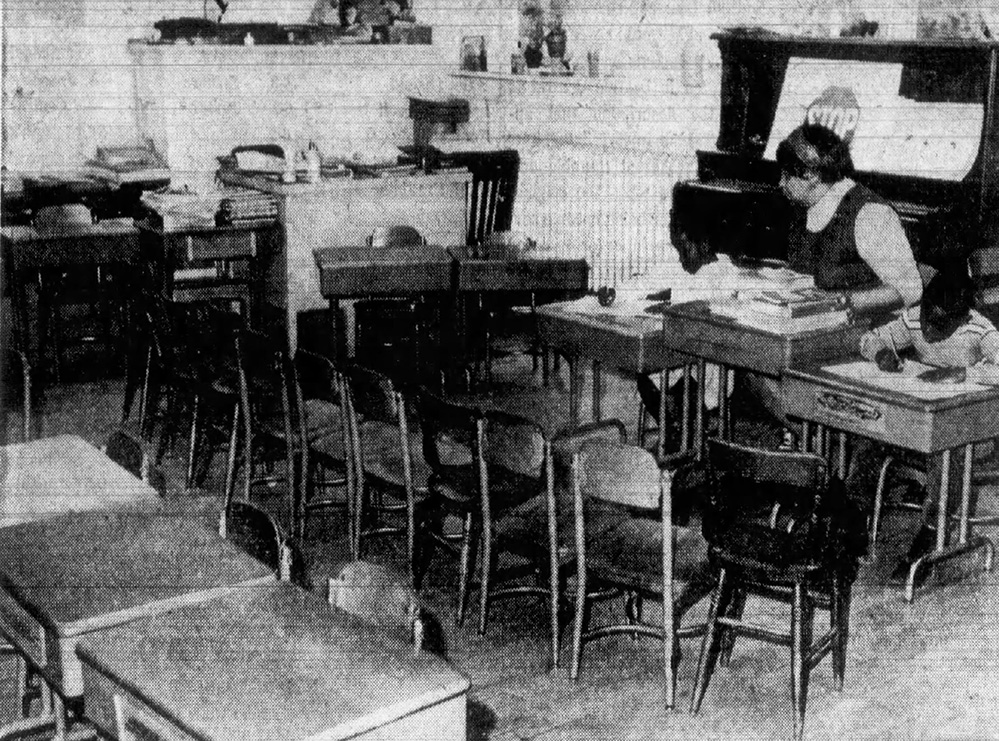

The Linden School’s poor conditions and overcrowding added to the NAACP’s motivation to dismantle segregation in the city.

Though nearly every student at Linden was black, six other elementary schools within two miles had black enrollment of less than 50 percent. Rebuilding the school at the same location, the lawsuit alleged, would cause “serious and irreparable educational and psychological damage to children who would be required to attend.”

Though the district repaired the ceiling, mothers feared sending their children back to the building after Christmas recess, said Lewis Steel, a civil rights attorney from New York who worked for the NAACP at the time.

Steel hired a young architect to inspect the building; the architect told a judge that the school shouldn’t reopen. The building was “a veritable fire trap, the very walls and roof of which were apt to immediately crumble or blow away in the face of a violent windstorm,” the architect testified during a preliminary hearing, according to court records.

Steel thought he had a slam-dunk case. But the city hired architects of its own who testified the ceiling wouldn’t collapse again. The judge declined to close the school.

When the Linden desegregation case went to trial, Steel was far from optimistic. A few years earlier, the NAACP had lost a similar case in Gary, Indiana. Because segregation in Gary schools was “de facto” — it stemmed from the city’s segregated neighborhoods and was therefore seen as unintentional — education officials weren’t required to make changes, a federal appeals court ruled.

So Steel devised a plan: He called on Linden teachers to testify on “every conceivable flaw with that school.”

“I decided to literally call as many teachers in the school as I could” who might testify on the poor building conditions and a lack of supplies, Steel said. “The lawyer for the school board called me up: ‘How many of these teachers are you going to call?’ I said, ‘I’m going to call every one I can get my hands on.’”

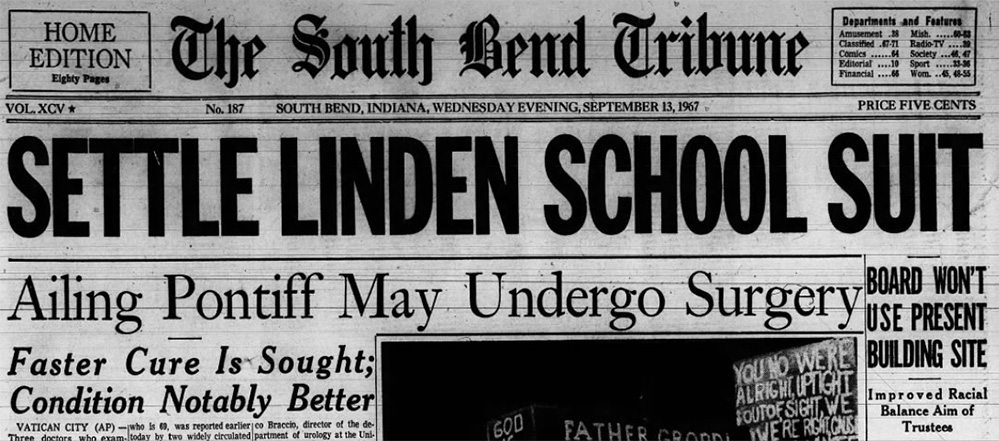

In a settlement, the district agreed to close Linden and devise an integration plan. But promises laid out in that court settlement remained contentious for more than a decade, with a South Bend Tribune editorial noting in 1979 that the plan was never carried out with “gusto.” The issue was far from over.

In 1978, the city’s education system came under federal scrutiny over “evidence of intentional discrimination,” according to the newspaper. The U.S. Department of Justice announced it might slap a lawsuit against the district based on a complaint over racial disparities in student discipline and the way it assigned students to campuses. A year later, as school desegregation plans lagged, the Justice Department sued. But just a few hours later, the district signed a consent decree — a federal court order to desegregate.

A key element of the decree is the “15 percent rule,” which requires that each school’s black student enrollment remain within 15 percentage points of the district’s overall black student population.

Additionally, the decree mandated that each school employ teachers with similar racial demographics and experience to the district as a whole. Students districtwide were to be provided comparable facilities and disciplined using similar practices.

Despite the participation of hundreds of South Bend residents in the city’s desegregation plan, the final decision was hotly contested and sparked several unsuccessful lawsuits. In one, parents sought to kill off the consent decree outright, arguing that the agreement deprived children of their right to attend schools in their own neighborhoods.

David Albert, a retired South Bend attorney, filed a separate lawsuit on behalf of black families — including the children of a school board member — challenging plans to close a school they said was already integrated. They city’s response to the consent decree, Albert argued, amounted to “resegregation.”

‘Plan Z’

Plan A failed. So did Plan B and Plan C.

For two decades under the federal decree, school assignment boundaries in South Bend went unchanged. But when the school system sought to update the antiquated plan, the community struggled to reach consensus. Then-Superintendent Joan Raymond, who died in 2017, proposed “Plan Z.” As in Gary, schools in South Bend were segregated largely by neighborhood; among the changes, the plan redrew assignment boundaries in a way that sought to decouple the racial demographics of schools from the communities in which they were located. Additionally, the district adopted a network of magnet schools to lure students to campuses in neighborhoods they likely wouldn’t consider otherwise.

That plan was updated in 2017. In addition to maintaining the magnet program, the district closed several campuses amid budget woes and declining student enrollment — a situation the superintendent has attributed to the rise of charter schools, private school vouchers and competition from neighboring districts.

Before the district implemented the latest plan, seven city schools had enrollment outside the consent decree’s “15 percent rule.” Today, five fail to comply. But John Borkowski, an attorney who represents the district, argued that concern over Buttigieg’s segregation comments was overblown.

“There’s never been sort of perfect compliance where all of the schools have been within the guidelines of the decree,” he said, adding that most campuses comply. Still, issues such as racially disparate student discipline rates remain a challenge, he said. “So the case isn’t over by any means.”

Black students account for more than 60 percent of suspensions and three-quarters of expulsions, according to district data.

The district’s ongoing desegregation efforts continue to draw critics. Among them is school board member Oletha Jones, previously education chair of the NAACP’s local chapter. Magnet schools in the city, she argued, create a “dual school system,” in which children in general education programs receive fewer opportunities. In high schools that house magnet programs, she said, there’s also within-building segregation: The demographics in the programs don’t resemble that of their campuses as a whole.

Jones has a point, Borkowski acknowledged. Each of the high school magnet programs serves a smaller percentage of black students than the campuses in which they’re located. At Adams High School, for example, black students account for 25 percent of the school’s population. But at the International Baccalaureate, a magnet program there, just 16 percent of the students are black. Measured on its own, the international program wouldn’t comply with the decree’s 15 percent rule.

But for Jones, the schools’ racial demographics are only part of the problem. The consent decree, she said, is about equity.

“It wasn’t just a focus on putting black and white together,” she said. “It was making sure the black children had the same resources as any other child.”

Addressing segregation — nationally

As South Bend residents continue to grapple with segregated schools, Buttigieg has confronted the topic on the campaign trail. While discussing the issue in North Carolina, he pointed to districts elsewhere in St. Joseph County, outside the city — comments that foreshadowed the education platform he released a week later.

“If you looked at the county,” he said at the North Carolina event, “almost all of the diversity of our youths was in a single school district.”

While children of color represent roughly three-quarters of students in South Bend, every other school district in St. Joseph County is majority white, according to state education department data. In three districts, nearly 90 percent of children are white.

Such patterns play out in communities across the country. But in 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in Milliken v. Bradley that the government cannot mandate racial integration across school district lines. Nationally, roughly 1,000 school district borders reflect deep divisions in terms of both race and per-pupil school funding, according to a recent report by EdBuild, an education think tank.

Buttigieg’s education plan devotes considerable space to promoting racial integration nationally, including a pledge to address stark racial divisions across district borders. With predominantly white and wealthy enclaves across the country seeking to secede from their local school districts, Buttigieg proposed a federal rule that would require communities to consider racial and socioeconomic integration when they seek to change district boundaries.

Under the plan, district border changes would “go through some evaluation of its impact and what effect that would have on segregation to demonstrate that it wouldn’t worsen things,” Buttigieg said during a recent presidential debate on MSNBC.

Additionally, Buttigieg’s education plan proposes $500 million in federal funds to incentivize local integration efforts and ends a restriction on using federal funds to support busing. As education leaders in South Bend grapple with racial disparities in student discipline, Buttigieg’s plan proposes a grant program for districts to reduce suspensions and expulsions and encourages state lawmakers to soften punishments for minor infractions like dress code violations.

More than five decades after Steel, the New York attorney, traveled to South Bend and helped residents shut down the Linden School, the 82-year-old expressed frustration with the persistence of school segregation in the city and in communities across the nation. In 1968, amid the campaign to desegregate South Bend schools, Steel was fired from the NAACP for penning an op-ed in the New York Times Magazine — titled “Nine Men in Black Who Think White” — that criticized the Supreme Court for retreating on civil rights enforcement.

But he hasn’t given up. There’s no reason that small cities like South Bend can’t fully integrate “except for the political reasons and the racial fears of white people.”

“There is no way in hell that you can’t design a system which is going to educate all children to the best of their ability,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)