Brown v. Board at 65: René Michelle Ricks-Stamps Recalls Delaware’s Deep Segregation — and Her Grandmother’s Outrage in Seeing School Buses Skip Her Home

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

My mother’s story of hardship started when her biological mother, who was of Asian descent, gave birth to a child whose father was of African-American descent. Her mother made what I believe must have been a difficult decision to not raise her own child. It appears she did not discuss her plans with anyone in authority. She simply left her infant, my mother, in a public space and walked away.

When my mother was found a few blocks from the train station in Wilmington, Delaware, a story appeared in the local paper about an abandoned infant. Sarah and Fred Bulah read the newspaper account and felt compelled to give this infant a home and decided to make her part of their family. In my view this was supposed to happen. It was fate.

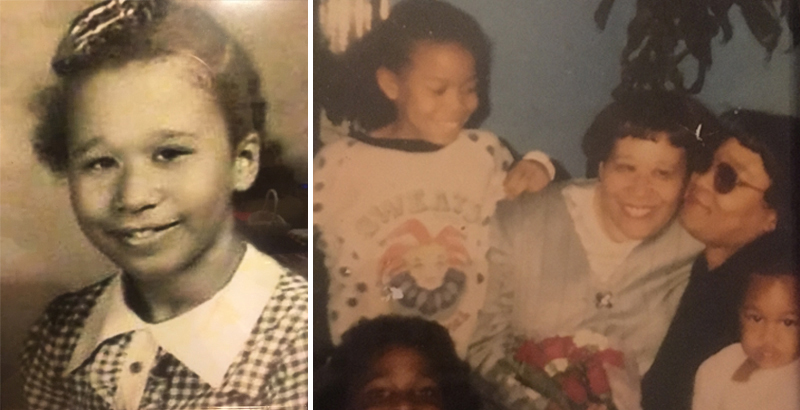

My mother was born in 1945, the day and month we do not know. But what we do know is that Fred and Sarah Bulah adopted her and named her Shirley Barbara. With the addition of Shirley, the couple had nine children in their household. My grandmother Sarah was quoted as saying: “She only wanted the best for her Shirley,” and, “All she wanted was for a child to get their due.”

Her eight siblings welcomed the infant and helped care for her. She quickly became the center of attention, and once she reached elementary school age, my grandmother grew more and more concerned about the circumstances still surrounding education for African Americans in Delaware. The other Bulah children were well past elementary school age and had been educated in the same segregated school that Shirley was attending.

As the story goes, a school bus transporting white elementary students passed their home every day, yet my grandmother had to drive my mother to the one-room school for African-American children. She was angered and frustrated that her youngest child was not able to attend classes at the large brick building with a playground and library. She could not tolerate one more moment that a school bus passed their home every day and would not pick up my mother because of the color of her skin.

My grandmother Sarah was known for often speaking with their church pastor about the injustices and indignities witnessed in the community. She became more and more concerned about the circumstances still surrounding education, the inequalities experienced by African Americans in Delaware. She talked to him about how women struggled to be recognized for their contributions and that it seemed they had no power to make things better for their children.

She confided in the church pastor that she could no longer stand idly by while black people were being spit on and beaten to death just because they wanted to use the restroom, get a drink of water, or board a bus and get a public ride home.

The pastor of their church listened politely but encouraged my grandmother to be patient and wait for change to come. She understood that he was not willing to take direct action, so she decided to write a letter to the governor of Delaware. The response to her letter made her even more determined. He told her the school district simply did not provide bus transportation for African-American children. The letter offered no apology nor promise to make change.

After receiving the governor’s reply, my grandmother knew it was time to take action herself, so she called local attorney Louis Redding. She discovered that he was already working with the NAACP on the matter of school segregation at the high school level in Delaware. With that, she moved ahead, asking him to help her on behalf of her elementary school daughter, Shirley.

Consequently, a case was developed to file a legal challenge to segregated elementary schools.

A small group of African-American parents had already pursued legal action in state court against racially segregated high schools. Their case involved only 12 children. They were successful in having their children admitted, but that did not apply to all high schools and did not open the doors for my mother.

My grandmother did not stop; to help her was Attorney Redding, who worked with members of the legal team from the NAACP headquarters in New York. Now the NAACP cases for Delaware challenged racially segregated high schools and elementary schools. The cases were filed together as Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart.

My grandmother’s case, on behalf of my mother, was heard as part of Brown v. Board of Education. In the aftermath of the Brown decision, my mother did not have an easy time attending integrated schools. My mother was quoted as saying that she was spit on and kids would put gum in her hair and pulled her hair. And many times she would need to call home and have Grandma come pick her up because things were unbearable.

René Michelle Ricks-Stamps is the daughter of Shirley Bulah and granddaughter of Sarah Bulah, who was a plaintiff in Delaware’s Belton (Bulah) v. Gebhart case that was later consolidated as part of the Brown v. Board Supreme Court case.

This testimonial is an excerpt from Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision, a new book spotlighting the original plaintiffs behind five pivotal school segregation lawsuits later consolidated by the Supreme Court. Read more first-person accounts, watch oral histories, learn more about the cases and download the book at The74Million.org/Brown65

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to The 74 and funded The Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research to produce the new book Recovering Untold Stories: An Enduring Legacy of the Brown v. Board of Education Decision.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)