Bradford: Are We Doomed to Repeat NCLB’s Mistakes on Accountability for Minority Students Under ESSA? The Devil’s in the Details

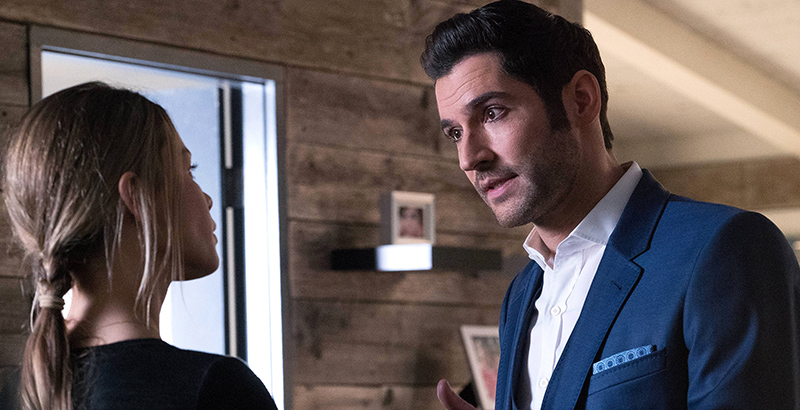

I’ve been cutting back on television lately, but one of my guilty pleasures is the campy Fox show Lucifer. Based on the eponymous comic from Vertigo, we follow our protagonist, The Lord of Hell and Light Bearer himself, on vacation in the City of Angels. Tired of keeping tabs on the lost souls who fill the underworld and weary of “Dad’s” machinations, the favored son has decided to roll with the mortals. He’s opted out of Hades and doesn’t want to play a game of Life that lasts an eternity anymore.

The show is fun, but it’s the show’s hell premise that’s relevant here. As in one of my other favorite shows, Preacher, hell is simply where people live out their worst memory over and over again. Indeed, in an amped-up case of “doomed to repeat it,” those confined to the underworld are forced to examine some unfortunate piece of their own history, forever.

I thought on this hellish notion when I read, recently, a Wall Street Journal article about ongoing tensions in the implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act. More specifically, many Democrats are concerned that a provision requiring the disaggregation of student data — for minority students in particular — will be disregarded. Indeed, 50 members representing the Congressional Black Caucus, Congressional Hispanic Caucus, and Congressional Asian and Pacific-American Caucus sent Education Secretary Betsy DeVos a letter saying as much.

The letter is compelling…I, for one, believe the collection of this data is one of the last backstops for kids of color, given the weak framework for school intervention “suggested” by ESSA.

But the truth is, this current moment is just like one we lived during the George W. Bush administration. And, in hindsight, we can see that moment back in 2005 as the opening of a door that the respective minority caucuses seek to close now (though the Obama administration’s waiver process may have shoved the door open wider, even if it did so inadvertently).

Not long after the stone tablets of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) started to make their way into the mainstream, some schools and districts started to push back. While someone probably knows what this looked like in red states, in deep blue New Jersey, where I worked at the time, many affluent suburban districts were most vocal. As AYP was based on progress made by all student subgroups — including minority students, even if in small numbers, as well as students with disabilities — otherwise high-flying schools that were largely white, wealthy, and cloistered in the state’s leafy burgs found themselves on “Needs Improvement” lists. In a state with such high property taxes linked to school assignments, and where expensive residential choice is a way of life, this was a bridge too far.

Instead of coming right out and saying, “We should not be dinged for these few minority kids we are not educating,” districts were smart and instead argued that because the groups of students were small, publishing the results of their subgroups would violate their privacy. Which is to say if the 10 black kids at the school are not making AYP, everyone will know exactly who they are. This was later reflected in No Child Left Behind guidance that allowed states to set their own “N” sizes — the population size above or below which test results can be excluded for the purpose of determining AYP.

“States must be concerned about setting ‘n’ sizes too low or too high,” the guidance read. “If states define subgroups as a very small number of students, while there may be a very high level of accountability for that population, judgments about how well schools are serving those populations of students may be based on a very small number of test scores and therefore may not be reliable enough. On the other hand, if states define subgroups as an overly large number of students — set ‘n’ sizes too high — schools may not be properly held accountable for the performance of all students because such schools may not have a very large number of minority, low-income, limited English proficient or special education students in their classrooms.”

To some, the move here may have been opaque, but among advocates it was clear as day. All students had to continue to mean “all,” because allowing districts to change their frameworks to “most” students opened a door to “these” and not “those” students. When you can exclude one student, you can potentially exclude any student, and this is the very notion with which states and members of Congress who supported ESSA now must deal.

It’s easy to forget that NCLB was introduced into a world that had homogenized away and obfuscated the chronic failure of minority kids for decades. Lawmakers traded away that certainty in an effort to soften the blow for schools that may have shown up on the “In Need of Improvement” list, even if those same schools faced no real consequences for that designation. And in doing so, they created the logical premise for the convoluted “maybe you get counted, maybe you don’t” rollout of 50 different state accountability systems under ESSA. For the Democrats who signed the letter — and let’s assume the veracity of their claims when they assert their belief that the secretary is undermining the spirit of the law as she approves state ESSA plans — this horse is out of the barn, and there may be no way to get it back in.

Whether it’s fiction beautifully illustrated on paper or theater that plays out on the grand stage of the nation’s capital, repeating our worst mistakes — or perhaps not learning from them — will always have consequences. Many said NCLB’s accountability framework was too restrictive, yet pivoting away from it has jeopardized the equity guardrails many in Congress fought to maintain. If it seems like an awful moment lived over and over again, that’s because it is. What comes next, however, may be even more troubling.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)