Boser: Students Want Learning to Be Easy. But for Learning to Be Valuable, the Brain Has to Struggle

A version of this essay appeared on The Learning Curve blog.

Lots of educational programs and interventions push easy ways for students to learn, especially many of the tech tools being used in the time of COVID-19.

As an example, consider the headline-making app DragonBox, which supposedly “secretly teaches math” to students via an algebra “game.” USA Today declared the app to be “brilliant.”

But as a learning tool, DragonBox appears to fall short, at least according to one study. Students using the app don’t appear to improve in their ability to solve algebraic equations, according to a 2014 study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University.

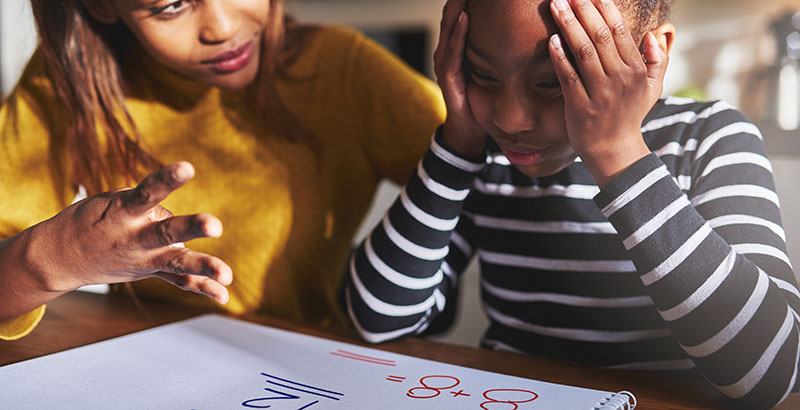

This issue is bigger than a single piece of technology or remote learning, though. Because at the heart of teaching and learning sits a discomforting truth: Gaining expertise is difficult.

But this bitter pill has an upside. Additional difficulty actually promotes learning. More struggle creates more understanding.

A growing body of cognitive science supports the idea that extra learning hardship leads to extra learning outcomes. UCLA researcher Robert Bjork argues that mastery is about “desirable difficulties,” while practice guru Anders Ericsson calls practice “hard work.”

In many ways, our brains are to blame. Mental struggle helps solidify memories. Hardship makes for more robust neuron pathways. This concept has important implications for teaching — and learning — and educators should do more to encourage a bit of cognitive exertion, especially at a time when students are learning online and it’s easier than ever to speed through an online course, glaze over an e-lesson or just watch a TED Talk that’s all sizzle and no substance.

It doesn’t take much to add a little difficulty to learning. Psychologist Stephen Chew routinely uses a simple experiment to demonstrate how a modest twist of struggle can improve learning. In his classes on the science of learning, Chew hands out a sheet of paper with approximately two dozen words on it. Half the audience counts the number of times the letter “g” or “e” appears in the text, while the other half focuses on the “pleasantness” of the words.

The results confirm the findings of an older study; people who did something a little bit harder like evaluating the pleasantness of the word remember as much as 40 percent more than those who don’t.

Barnard College psychologist Lisa Son provides another example, using an imagined student named Moe to illustrate the process of making learning harder in ways to promote additional “desirable difficulties.”

In Son’s example, Moe has submitted an essay with multiple spelling errors. Rather than simply marking the spelling errors, she recommends prompting Moe to glance at the page himself and find the mistakes on his own. As Son explained to me, “as the student reads more on their own, they’ll see the word spelled correctly, and they’ll never forget the right answer.”

The value of struggle is at the center of the educational process. Students need difficulty, no matter what genetic assets that they bring to the learning table. For instance, I once met up with wunderkind mathematician Jordan Ellenberg. By age 3, Ellenberg could read road signs; by 8, he could do high school-level math; and at 17, the Washington Post dubbed him a “true genius.”

As a child, he believed that struggling indicated a lack of intelligence. But after spending years working at the highest level of math, he realized that learning demands difficulty. As Ellenberg told me, “You have to have an incredible tolerance for failure.”

It was this attitude, this embrace of learning hardship, that helped Ellenberg eventually become a professor of math at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, with a collection of well-regarded articles and books to his name.

Still, building struggle into the curriculum isn’t easy, especially as learning goes online. Certainly, kids don’t want learning to be hard. But for teachers and schools, it’s important to reframe learning, underscoring that the difficulty of gaining expertise is what makes the experience a valuable one. Or as a math professor told me: Math isn’t fun. But that’s what makes it worth doing.

The same is true for all learning.

Ulrich Boser is the founder of The Learning Agency and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)