Book Excerpt: The Power of Who You Know, How Schools Can Catapult Student Success By Building Their Social Networks

This essay is excerpted from Who You Know: Unlocking Innovations That Expand Students’ Networks by Julia Freeland Fisher. The book explores “how schools can invest in the power of relationships to increase social mobility for their students,” particularly low-income students of color.

It’s not every day that you get the chance to meet your idol. And it’s not every day that that idol takes you under his wing and launches you into an incredible career pursuing your passion.

But for Bear McCreary, that’s basically what happened. McCreary is arguably one of this generation’s break-out composers. He’s written scores for hit TV series like Outlander and The Walking Dead. But for all of his raw musical talent, McCreary, by his own account, got his first big break because of an unlikely chain of connections. It began in the coastal town of Bellingham, Washington, where McCreary grew up. As he describes it,

In the winter of 1996, I was awarded “Student of the Month” by the local Rotary Club. I got to ditch class for an afternoon to attend the ceremony where I was introduced to the members and got a free lunch. My adolescent brain was bored beyond belief. … I found myself actually yearning to be back in Social Studies! During the event, they mentioned my interest in film music and that I was curious about attending the University of Southern California, famous for its Film Scoring Program.

After the luncheon, I scrambled to get out, but I was stopped by a kind-looking gentleman who introduced himself, Joe Coons. He said he was struck by my interest in film music, because he had a friend in the industry. I must confess, even at this young age, I was a little cocky, and assumed he was about to talk about someone who scores the local news or public access weather updates.

“Have you heard of Elmer Bernstein?” he asked.

Elmer Bernstein was one of the composers I most admired! … Joe Coons was active in the Bellingham boating community. He knew Elmer because Elmer kept his boat in the marina, and each summer, he would sail up the Canadian coast to Alaska. The cosmic coincidence is staggering. … A few months later, I heard from Joe that Elmer was willing to sit down and chat with me the next time he came to town.

That afternoon, at the Rotary Club, I learned to never take a boring luncheon for granted. To this day, Joe Coons still gets an autographed copy of my every soundtrack album.

© 2014 Bear McCreary

McCreary would go on to work as one of Bernstein’s protégés for nearly a decade until the legendary composer passed away in 2004.

Bear’s heartwarming tale may sound like an anomaly. A random, “cosmic coincidence,” to use his words. But it is also a tale of relationships transforming a self-professed bored and cocky teenager’s outlook. It’s a story about how an institution as simple as a local luncheon can broker new connections between two people who might otherwise not meet. And how a single mentor may change the course of our lives.

It’s also a subtle testament to the fact that a chain of relationships is a powerful lever. We all stand to benefit from our own proverbial Elmers as professional mentors. But we also benefit from proverbial Joes who can help us find our Elmers along the way.

Given the powerful role that relationships play in our opportunity equation, the urgent question facing schools is how cosmic coincidences like Bear’s might become the rule — rather than the exception — in their students’ lives. How might schools take the chance out of mere chance encounters? And how, in particular, can schools begin to broker new connections for those students on the wrong side of relationship gaps, whose chances of finding mentors lag their already better-connected peers? How could schools move beyond functioning as enclosed communities to being deliberate brokers of whom students know, becoming hubs for their social capital to flourish?

Integrating social capital into the architecture of school

Social capital refers to the notion that our networks contain real value to help us get by and get ahead. Readers who work inside of education may be wary about undertaking efforts to invest in students’ social capital. This could end up as yet another in an endless list of tasks piled onto teachers’ and administrators’ plates. Luckily, innovation theory suggests that these efforts could offer a huge payoff. By investing in the social resources at students’ disposal, schools could start to produce breakthrough academic and postsecondary outcomes for their students. The very results, in fact, that previous decades of reform have struggled to produce.

Put simply, by integrating more factors that influence students’ lives into their designs, schools stand to boost performance. This phenomenon is actually well studied beyond education. Across industries, when firms are trying to improve dramatically, they often wrap their arms around the various and sundry components that stand to impact performance.

All products, services, and systems have an architecture, or design, that determines what its parts are and how they must interact with each other. The place where any two parts fits together is called an interface. In circumstances when organizations are aiming to radically improve the performance of their products and services, integrating across these interfaces is crucial. When organizations do this, they are pursuing a particular structure: an interdependent architecture.

A service’s architecture is interdependent if the way one part is designed, made, and delivered depends on the way other parts are designed, made, and delivered — and vice versa. Successful enterprises pursue interdependent architectures when they want to improve a product, service, or entire industry.

Take Gustavus Franklin Swift’s innovative approach to marketing beef in the late 19th century.

In Swift’s day, beef was sold on a strictly local basis. At the time, butchers couldn’t ensure that the meat could stay fresh over long train rides to far-flung customers. But Swift was determined to create an economy of scale: he centralized butchering in Kansas City, which meant he could process beef at a very low cost. Then Swift designed the world’s first ice-cooled railcars so that his wares could remain fresh over long distances. In other words, because there was no way to outsource distribution, Swift had to become a refrigeration maverick—not just a beef butcher—in order to innovate. By building a business in which butchering and transporting beef were interdependent, he was able to revolutionize the beef industry as a whole.

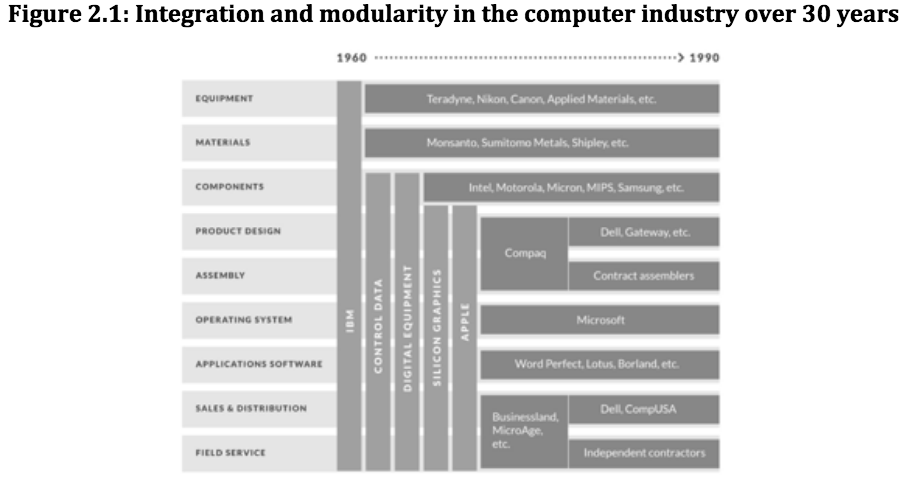

The phenomenon of interdependent architectures driving breakthrough performance holds true in other industries as well. For example, in the early days of the computing industry, tweaks to any one part of a computer — like the operating systems, core memory, and logic circuitry — would impact all of the others. To build the best machines in the world, industry leaders like IBM could not merely assemble mainframe computers from prefabricated parts. Instead, IBM had to control the entirety of production to build better and better performing machines. Until, that is, it could build a product that met customers’ demands. Then, and only then, could it begin to define and outsource discrete component parts.

Companies and industries rarely remain in a highly integrated state forever. Over time they modularize. Unlike an interdependent architecture, in a modular architecture, there are no unpredictable interdependencies in the design of the service’s parts. Modular parts fit and work together in well-understood, crisply codified ways. Modular components can be developed in independent work groups or by different organizations working at arm’s length. Modular architectures, while limiting firms’ ability to innovate to new heights, optimize for efficiency and flexibility. Customers can mix and match modular parts to customize to their liking.

Why schools’ modular architecture costs students

Schools may feel far afield from personal computer manufacturers or beef distribution channels, but there is at least one important similarity. Many schools, particularly those serving low-income and minority students, are not producing the great results that policies or the public hope and expect of them. Schools falling short on performance find themselves in a similar “not good enough” position as IBM did in the early days of the mainframe computer and Swift did as he struggled to expand his business beyond Kansas City stockyards.

Through the lens of theory, our decades-long struggle to close race- and income-based achievement gaps suggests that schools may be living the consequences of a system that has prematurely modularized. The different components that make up a student’s life chances and academic success — like health care, support services, academics, and diverse networks into the knowledge economy — currently fit into stubborn silos. Strict interfaces separate what happens inside of school from what happens beyond it. All the while, out-of-school and non-academic factors inevitably contribute to student performance.

This “modular” architecture severely hamstrings schools’ ability to innovate toward better outcomes for all students.

“Outcomes,” of course, is a loaded term in schools today. However wide-ranging our ambitions as a society are, in recent decades standardized test scores have become the de facto metric for judging how well the nation’s schools are performing. And against these albeit narrow measures, although low-income students and their higher-income peers have both posted gains, the achievement gap between these groups has barely budged over the past decades. In recent decades, data on similarly troubling gaps has emerged further down the line when it comes to access to opportunity among poor adolescents and young adults: only 9 percent of low-income students earn a bachelor’s degree by their mid-20s, compared with 77 percent of their wealthy peers. And even further down the line, with an estimated half of jobs coming through personal connections students network — into potential employers — also matter immensely.

To tackle these achievement and opportunity gaps, schools serving low-income populations would benefit from an interdependent architecture. Schools need to integrate far beyond their core competency — delivering academics — to produce dramatically better and different results.

By this logic, in light of the gaps in access to social networks, schools will need to tackle the social aspects of students’ lives. They will need to adopt a new, interdependent architecture that integrates the value of strong- and weak-tie relationships into their designs.

This is obviously easier said than done. Investing in students’ strong-ties that can offer sources of care or support into traditional school models can prove daunting. School systems often lack the capacity and funding to offer a wide array of non-academic services. And establishing coherent and effective partnerships across youth services providers and with students’ families and communities poses a formidable task. Public policies often create silos that separate academic services from other supports, like community-based mentorship, health care or family support services. Disparate funding streams, in turn, constrain schools’ abilities to incorporate these services into their existing systems and processes in an interdependent way.

Integrating access to a diverse array of weak-tie relationships into the architecture of school may also introduce potentially difficult logistical challenges. Not to mention, the more connections a school facilitates, the greater the possible risk to children’s safety and privacy.

But the potential on the other side of an interdependent architecture is immense. Just as theory would predict, schools that are beginning to integrate social supports and deepen students’ networks are producing breakthrough results that have long eluded schools, especially those serving low-income and minority students. Luckily, we’re beginning to witness emerging innovations that stand to strengthen students’ strong-tie networks and diversify their weak-tie networks.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)