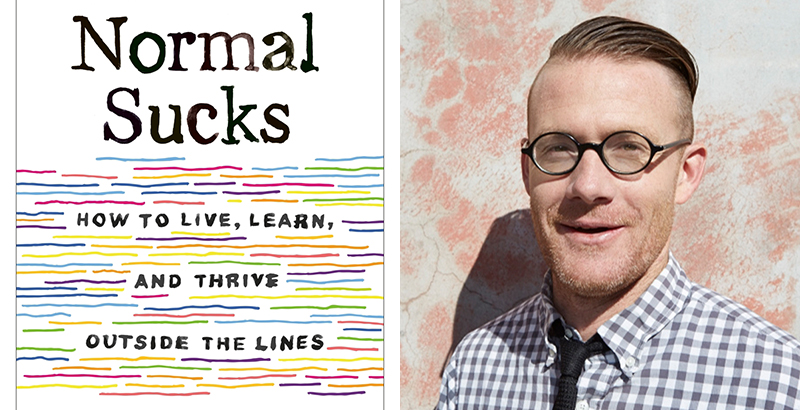

Book Excerpt: A Former Special Ed Kid on Learning Differences, Our Educational System and Why ‘Normal Sucks’

Excerpted from Normal Sucks: How to Live, Learn, and Thrive Outside the Lines by Jonathan Mooney. Copyright © 2019 by Jonathan Mooney. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company.

From my first day in kindergarten at Pennekamp Elementary School, me and school just didn’t get along. It started with the desk. My relationship with my school desk was fraught: five seconds into class, my foot starts bouncing; 10 seconds in, both feet; 15 seconds in, I bust out the drums. After a few minutes, it’s all over. Then I’m trying to put my leg behind my neck. No, that desk and me did not get along. For some kids, their desk was simply school furniture; for me, it was an enhanced interrogation technique that would have made Dick Cheney smile.

Sitting still was hard enough, but I also struggled with reading. I was placed in the “dumb” group. Teachers didn’t actually call us the dumb group, but let’s be real: Everyone knew which group was the “smart” group and which wasn’t. My school had the California Condors, the Blackbirds, the Bluebirds — and then over in the annex trailer behind the actual school were the Sparrows. I spent the day reading See Spot Run while the Condors were finishing up War and Peace. All joking aside — no matter what the reading groups were named, kids knew their place on the intelligence bell curve. See Spot Run is not a bad book. Nice narrative structure. Good moral tale. But I didn’t want to be caught dead with Spot when I was 10 years old. So as I headed across the room to find my reading group, Spot went in my backpack, or under my shirt, because as I walked by, the other kids would taunt: “Jonathan, go back to the dumb reading group.”

Reading groups sucked enough, but reading out loud in class was pure hell. Here is how it went for me: First kid starts reading; I’m terrified but have a plan — count the number of sentences this kid is reading, then flip through the book to memorize. Next kid reads. Oh, no. The first kid reads 10 sentences; the next kid reads five. I can’t find my page. The kid right next to me starts to read. I’m next. I raise my hand. March myself into the bathroom and pray to God I will be skipped when I come back. I come back from the bathroom only to discover that they’ve waited for me. Held my page. I read out loud for 10 agonizing minutes, though reading would be an ambitious term for what I did. Fumbling through letters and words would be more accurate.

Then there was writing. I asked my third-grade teacher why couldn’t there just be one there. Do we really need three theres? And can’t we just agree when I write how instead of who, or who instead of how, that he could still get the gist of what I was trying to trying to say? Okay, this could be a problem sometimes, like when I passed a note to a kid next to me, intending to ask them how they were doing, but instead asking them who they were doing. But that is (a) not all that often, (b) funny and (c) at some point in life a valid question.

And then there were words like horse and house. Sure, these are totally different things. But give me a break. That r in the middle of horse? Not my problem. Then words like organizations (which often comes out as orgasm) and business (which I write as bunnies) that, due to all those soft consonant vowel blends, can be mangled and rearranged in endless, beautiful ways. Okay, these words have none of that, or maybe they do. I don’t know, because I still don’t know what the hell a consonant vowel blend is.

There was a time where we all just agreed to let this stuff go. Sure, that time was the 1500s and spelling wasn’t codified, but people got by. One word could be spelled 10 ways. Those were the good old days. Pennekamp Elementary School, however, did not believe in the restoration of Old English spelling conventions, so I learned to dumb it down. I would write only with words I could copy from around the room. If the word in my head was too long for me to spell, I used a simpler one. When in doubt, I’d scribble a word so no one could read it. I became caught in a full-blown dumb-it-down cycle. My spelling and writing made me seem stupid, so then I was treated as if I was stupid. Then I began to believe I was stupid, and then I began to act stupid, and then — do it all over again the next day.

By the end of third grade, I was promoted from being one of “those kids” to the “resource room special ed” kid. I was diagnosed with multiple language-based learning disabilities and attention deficit disorder. When the educational psychologist broke the news to my mom and me, it was as if someone had died. Tissues on the table. Hushed tones. Mirrors covered. We sat shiva for the death of my normality. The tragedy of my problem — which up until that point hadn’t had a name — wasn’t lost on me, even at 10 years old. I knew people thought something was wrong with me. When we left the shrink’s office, I asked my mom, “Am I normal?”

I can still see my mom that day in my mind. She is not a tall woman; on a good day, she’s 4-11 in high heels and looks like an Irish bulldog. She has a squeaky voice like Minnie Mouse’s and curses like a truck driver. That school psychologist did not want a pissed-off, cursing Minnie Mouse in her office. But that’s where my mom went. She asked me to stay outside and then she went back into the office. Next thing I knew, every dog in the neighborhood was running away and I felt as if glass would shatter under the wave of her high-pitched obscenities. She walked out of the office and answered my question with two words: “Normal sucks.”

Regardless of what she said, though, I knew the real answer. I had crossed that invisible line between the normal and the not normal, which we all know is there. Though we aren’t quite sure where it is all of the time, or who drew it, or how, or why. At that moment, I knew for sure that whatever normal was, I wasn’t it.

I want you to know that my story doesn’t end outside that office, with me on the wrong side of normal. I want to tell you how I fought my way back, not to the “right” side of the line, but to a sense of self and life that isn’t defined by that line at all.

Diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD as a kid, Jonathan Mooney didn’t learn to read until he was 12; he often heard that he was lazy and stupid and would probably end up homeless or in jail. Today, he’s a New York Times best-selling author, an Ivy League grad and a disabilities rights advocate speaking about neurological and physical diversity, inspiring those who live with differences. His books include The Short Bus and Learning Outside the Lines.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)