Book Excerpt: 15 Years After Katrina, New Orleans School Miracle Emerges as a ‘Surprising’ Mix of Free Market Choice and Strong Government Accountability

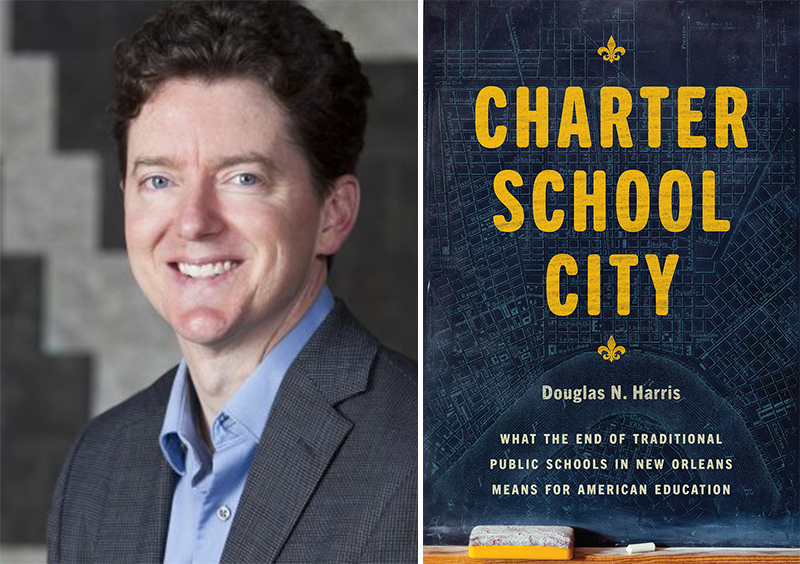

This excerpt is adapted from the upcoming book Charter School City: What the End of Traditional Public Schools in New Orleans Means for American Education by Douglas N. Harris, reprinted with permission from the University of Chicago Press. © 2020 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. The book, which will be published Sept. 1, explores how New Orleans seized on Hurricane Katrina to produce unprecedented — and successful — reforms in the city’s schools.

New Orleanians have an affinity for their schools.

One of the first questions the city’s natives ask when they meet someone is: “What school did you go to?” At the festive balls held during the city’s Mardi Gras season, announcers introduce the members of their “krewes” by name and high school over the loudspeaker — even if they graduated half a century earlier.

But until quite recently, New Orleans may have been the last place on earth one would have expected innovation in the schools. As one writer put it, the city was “drenched in the past.” The popular affinity for the schools. The centuries-old traditions of music and Mardi Gras. The historic French Quarter, with its eighteenth- and nineteenth-century architecture. Crime and corruption. Racism and segregation. In many respects, New Orleans in 2005 looked much as it had in the 1800s. It was not likely to change anytime soon. But as students started school in the fall of 2005, things were about to change. It was hurricane season, and a storm was brewing in the Atlantic. Later that week, they would give it a name, Katrina.

The city, and its schools, would never be the same.

On August 29, 2005, the eye of Hurricane Katrina made landfall just east of New Orleans. More than a thousand people died and $160 billion worth of property was lost throughout the Gulf Coast. It was one of the worst disasters, more man-made than “natural,” in American history, its effects exacerbated by a lack of planning and decades of questionable infrastructure decisions. In the hurricane’s wake, most cities in the region worked to rebuild their prior ways of life, including their schools, as they had been before. They cleaned out sludge-filled school buildings and rebuilt those that had been destroyed. Elected board members returned to dry off their binders of policies and procedures. Teachers came back to the same lesson plans and updated editions of old textbooks. Everyone in these schools was changed personally by this traumatic and catastrophic event, to be sure, but the basic institutions meant to serve their needs were generally left as they had always been.

New Orleans did something different. In this city — and only this city — state leaders decided to remake the school system in a new image. Instead of restoring the system of government-based school districts, the state turned almost all of the schools over to a state agency that, over time, turned them all into privately run, nonprofit charter schools. Instead of governing schools through district rules, superintendents, and union contracts, charter school leaders took control over almost all major educational decisions. Instead of trying to ensure educational quality by training teachers, giving them job security, autonomy, and steady pay, and encouraging them to use their best judgment, charter school leaders were allowed to hire and fire teachers as they pleased, without certification or tenure rules, and to pay them as they wished. Instead of having their children assigned to schools based on where they lived, families could, in principle, choose any school they wanted; attendance zones were essentially abolished, and government funding went to the schools families chose. Instead of replacing the principal if a school faltered, the district or state could take it over, dismiss the entire staff, and either run the school itself or turn it over to another charter operator.

Reform critics sometimes decry the application of economics-based management to schools as coldhearted and ignorant of what schools do and why people decide to become educators. Staunch defenders of the system, like Diane Ravitch, point to a real and sometimes sordid history of profiteering and scandals that have plagued similar efforts in the past, not only in schooling but other areas where the government has turned over control to private organizations. These are all reasonable concerns, but the seeming allergy to the market concept does not change one basic fact: Schooling really is a market. It is a service that has a supply side (schools) and a demand side (families). Parents pay, often dearly, for educational services for their children. School leaders have to make decisions about the use of scarce resources. This is what markets do. Trying to understand how schooling works without acknowledging its market nature is like trying to understand how a plane flies without acknowledging gravity and other elements of physics.

There was, at the time Katrina struck, some evidence about market-oriented approaches, but it was based on programs implemented on a small scale where traditional public schools were still dominant, and therefore was not very informative about what a full-fledged free market would look like. Also, even where reforms seemed to work well, based on what we could measure, there were good reasons to be skeptical of what was unmeasured. For the leaders who held the fate of New Orleans’ schools in their hands after Katrina, the theory and the evidence were inadequate to the momentous challenge before them — creating a new kind of school system.

Nonetheless, the city’s schools had been failing by any measure before Katrina, and some leaders demanded a change. Since the system was driven substantially by the government and unions, the reformers’ natural instinct was to shift control to markets. Under the traditional school system, the government operated schools. These reformers wanted the government only to govern schools and to hire others — autonomous private organizations — to run them under contract. They wanted the government to pay for and steer the boat, but not to row it. After Katrina, they would finally get what they wanted.

My belief, before I even stepped foot in New Orleans, was that this unprecedented reform effort deserved an unprecedented effort to understand it. I initiated one of the largest studies of a single school district ever conducted, involving more than thirty academic reports and using almost every conceivable type of data and analysis.

When I began this work, in the fall of 2012, I did not know what to expect. The city’s academic trend lines were impressive, but I had seen supposed success stories end badly before. During the 1990s, Texas governor George W. Bush introduced test-based accountability reforms that produced strong gains on the state’s high-stakes tests. This “Texas miracle” helped propel the governor into the White House, where his administration spearheaded the sweeping No Child Left Behind (NCLB) federal accountability law. Additional analysis, however, suggested that the Texas policy had no effect on more trusted low-stakes tests. For the other most relevant reform, charter schools, the results had been similarly unimpressive at the time Katrina made landfall. The average charter school at that time was still lower-performing than the average comparable traditional public school. Some charter schools seemed to produce great results, but there were signs this was accomplished by selecting the students they wanted and pushing out students who had more challenges and pulled school scores down.

I came to New Orleans with an open mind. I did not have a strong view on these types of reforms. Years later, and with a dozen articles published in prominent peer-reviewed academic journals, it now appears that New Orleans is an outlier, in almost every measurable way. The reforms significantly improved a wide range of student outcomes, on average and for almost every identifiable group — rich and poor, black and white, low and high-achieving. The positive effects also emerged without most of the negative side effects that have plagued similar reforms in other parts of the country. I have not seen other cities, or other programs, able to generate such large gains across so many metrics.

“Miracle” was one word used to describe the change, though that implies that no further improvement is possible (how can you do better than a miracle?) and that we do not understand how it happened. In reality, we designed our work to learn whether it worked as well as how, why, and in what sense. The clearest contributor to improved academic outcomes was also the most controversial: taking over low-performing schools. Why did this matter so much? Prior studies had generally found no effects, or even negative effects, of school closures and takeovers. Why were the results so different in New Orleans? And why did the other mechanisms, like school choice and competition, seem to matter less, or at least less directly?

With partial answers to each of these questions, we could begin to address the larger question: What is the role of government in schools? One possibly surprising conclusion of my analysis is the New Orleans experience actually undercuts the argument for free markets in the case of schooling. How can this be, given that the New Orleans reforms were both market-based and so successful? The answer is that the reforms took place in two distinct stages and forms. Early on, what was in many respects a free market yielded some improvements but also most of the problems that market theory predicts. Those problems led the state to get much more involved, and the results improved even more. The implication is that the flexibility and pressure that come with markets can be useful but still work best with government as a partner — a different sort of partner than the school district had been prior to Katrina, but an active partner nonetheless.

The New Orleans experience is important. First and foremost, it is important to the children of New Orleans. With everything the city’s children went through — the deaths of friends and loved ones, dispossession of homes and property, and massive disruption of daily life — they deserved a quality school system to help them put their lives back together. It also matters because New Orleans provides a proof of concept, showing that this type of reform can produce significant, measurable academic improvement. Most education policies and programs have no measurable effect. Some have positive effects on some outcomes but not others. New Orleans is the rare case where we see large gains on a wide variety of measures, from test scores, and high school and college graduation rates, to parent satisfaction.

We need to understand why this case turned out so much differently than the norm. One common counterargument is that the New Orleans experience is so unusual that it may be hard for those in other places to draw any lessons. In terms of the process of reform, that is true. The New Orleans school reforms sprang from a disaster that I hope will never happen again anywhere else. The process the reformers used to put the reforms in place made matters worse, leaving lasting wounds that have made such reforms anathema in many big cities across the country. In addition to being unfair, their approach may have been unwise as it bred discontent that led many community members to ignore or distrust the measured results, threatening the long-term sustainability of the New Orleans reforms.

The evidence suggests that the New Orleans reforms were effective in part because leaders responded to market failure by redefining the appropriate roles for government. They did not rely solely on parents to “vote with their feet” and exit low-performing schools. If they had, in this unusual kind of market, they would not have seen so many metrics rise. Instead, through the closure and takeover process, the state stepped in to close large numbers of low-performing schools — imposing government accountability on top of market accountability. Economic theory and evidence also predict that schools will try to choose students as much as students choose schools. Seeing this occur during the free market phase, reform leaders required schools to provide transportation and eventually stepped in to manage enrollment to ensure broad and fair access.

New Orleans leaders did not get everything right, but it was certainly better than other plausible options, and it got better over time. This analysis, combined with evidence from across the country, also suggests some broader lessons. There are five fundamental roles for government that seem to apply under just about any conditions: accountability, access, transparency, engagement, and some form of choice. This list should be viewed as a set of minimum standards and is, in most respects, more limited than what school districts normally carry out. Conversely, it is more extensive than the list that might be submitted by advocates of free-market approaches like school vouchers. A further implication is that something akin to traditional school districts, even after a century, is probably still one of the best options available in most places. This may be the most surprising conclusion of all given how effective this market-based reform was in New Orleans. It becomes less surprising when we consider the continued advantages that have led government school districts to be so popular for so long.

Whether you support or oppose these reforms, what happened in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina is one of the seminal events in the history of American education. The policies adopted there represent a wish list that many reformers had been talking about for at least a quarter century, implemented suddenly and comprehensively for the first time. Simply observing New Orleans is an eye-opening experience. Having studied school systems and reforms for more than a decade before arriving in the city, it took me several years living in New Orleans, as a parent, researcher, and community member, to rewire my own ideas about the ideal school system in a way that allowed me to really understand what was happening.

Observing something like a traditional school district on a daily basis for so long, its key traits can become invisible even when they are right in front of us. A century-old school system can do that to people. It took one of the worst-ever tragedies to push New Orleans schools off the well-worn path of the traditional school system. By telling the various sides of the story, we can learn from the experience of New Orleans, honor the victims of Hurricane Katrina and the injustice they endured, and place the country on a better path toward serving all of the nation’s children well.

Douglas N. Harris is the chair of the economics department and the Schlieder Foundation Chair in Public Education at Tulane University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)