Black Kids in Michigan Often Stuck in Classes With More Than 40 Kids, New Study Reveals

In a single Detroit elementary school class, 60 students are packed together in one room; some sit on overturned milk crates because there aren’t enough chairs to go around.

This is an extreme case. But a report, issued in September, finds that across Michigan, black and low-income students in urban areas — unlike their white, affluent, suburban peers — are often stuck in large classes of more than 40 kids. The state has no cap on class size.

The research could provide fodder for a recently filed federal lawsuit that alleges Detroit schools in particular are unconstitutionally bad and underfunded.

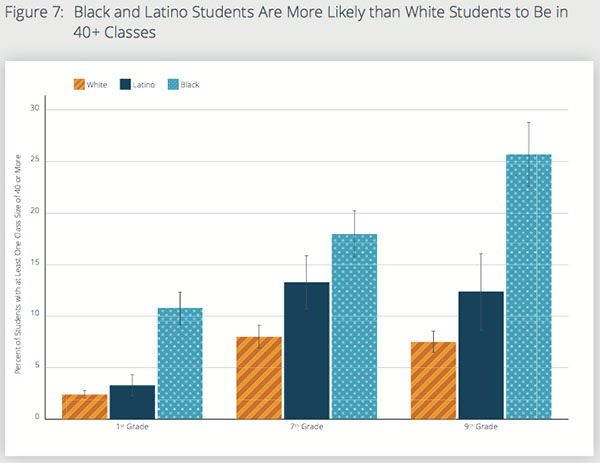

The study found that black ninth-graders are more than three times as likely as white students to be in a class of over 40. Those are the same type of students who research shows are most likely to benefit from smaller class sizes.

Brian Jacob, Rene Crespin, C.J. Libassi, and Susan Dynarski, of the University of Michigan, uncovered this disturbing racial disparity by examining students’ courses, sections, teachers, and grade performance for individual classrooms statewide, and complementing that data with information about specific schools, such as location, racial makeup, poverty level, and test scores.

The researchers found that class sizes overall are significantly larger than suggested by the 18:1 student-teacher ratio reported statewide. (Student-teacher ratio doesn’t account for specialized teachers who work with small groups of kids rather than presiding over a regular classroom, or for breaks and prep periods that remove teachers from the classroom; for this reason, the student-teacher ratio understates the number of kids per class across all grade levels.)

For example, they found an average of about 25 students per class in first grade and approximately 30 per class in ninth grade.

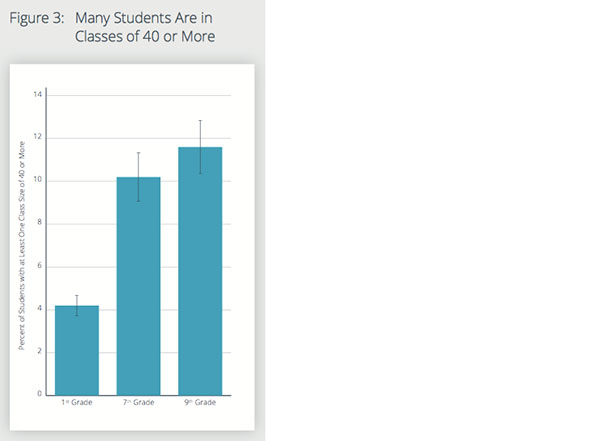

When looking at the share of students who had at least one class of more than 40 students, the study found the percentage of seventh- and ninth-graders assigned to extremely large classes was in the double digits.

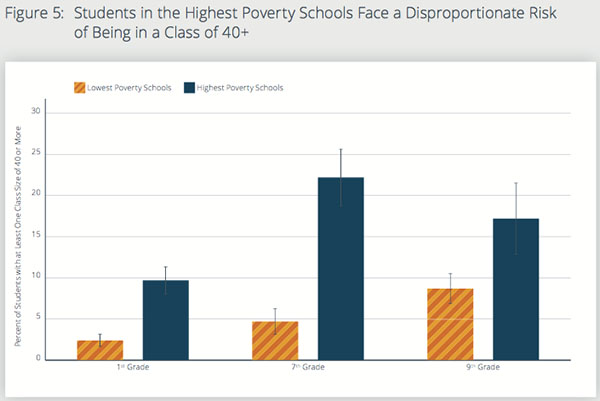

When the researchers examined who those students were, the results were striking. Black students, students in high-poverty schools, students with low test scores, and students in urban areas were far more likely to attend class with 40 or more students than their white, wealthier peers.

For instance, over 20 percent of seventh-graders at the highest-poverty schools were in large classes, compared with fewer than 5 percent of those in the lowest-poverty schools.

And when examining differences by race, the numbers were stunning: In ninth grade, over a quarter of black students attended at least one class with 40 students or more; just about 7 percent of white students had a class that large.

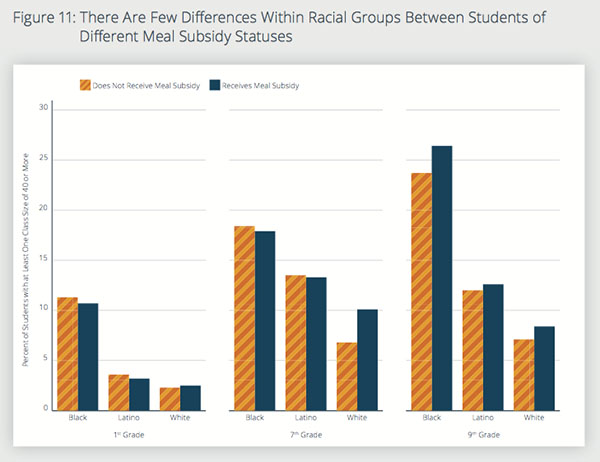

These results seem to be driven by race more than by economic status, because when controlling for race, differences by poverty largely disappear. In other words, a poor white student is far less likely to attend a large class than a wealthier black student.

It’s not entirely clear what’s causing these inequities. The study showed that the disparities are not between different student populations at the same school, but rather between different schools.

A report from the Education Law Center found that Michigan spends about the same amount per student in high-poverty and low-poverty schools, suggesting that inequitable funding may not be the main culprit. However, there may also be resource disparities by race, rather than socioeconomic status, that are not captured by the funding report. High-poverty, urban districts may also spend more on teachers who don’t have their own classrooms, like co-teachers, special education teachers, and reading specialists.

Another possibility is that schools serving more mobile populations of students may have trouble maintaining small, stable class sizes because of budget uncertainties introduced when students move schools frequently. The report found some support for this, showing that class sizes in urban areas are significantly smaller when not counting students who switch schools mid-year.

There have long been debates about the value of small class sizes. Research has shown that students, on average, do better in smaller classes, but large reductions class size are difficult to implement and quite expensive, leading some to argue that such reductions are not cost-effective. This debate hasn’t been settled in the research literature.

But what is fairly clear is that black, low-income students benefit the most from small class sizes — in other words, those who stand to gain the most are precisely the ones disadvantaged by the distribution of class sizes in Michigan schools.

Notably, the class size debate tends to center on the difference between, say, 25 and 20 students in a class — not 40, or even 60, students packed into a single room, perhaps without enough supplies or chairs.

Research doesn’t tell us the effects of classes that large, but common sense probably does.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)