To the extent that it taps into frustration with school performance, and with the recent headlines about America’s drop in international test scores, the sentiment seems innocuous enough, and DeVos is not alone in perhaps mythologizing the public schools of the past.

But a deep look at the data indicates that student performance has been improving — or, at worst, remaining flat — across a variety of measures, in some cases, for decades. That doesn’t mean American schools can’t get better, but DeVos’s promise to make education great “again” may be harking back to a heyday that never existed.

The Trump transition team did not respond to a request for comment.

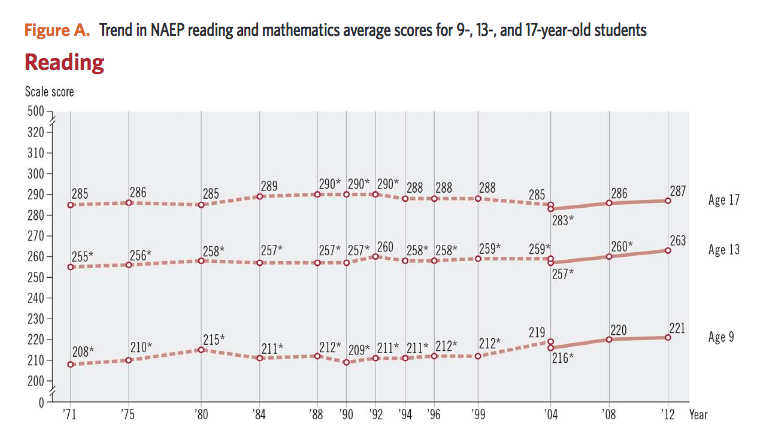

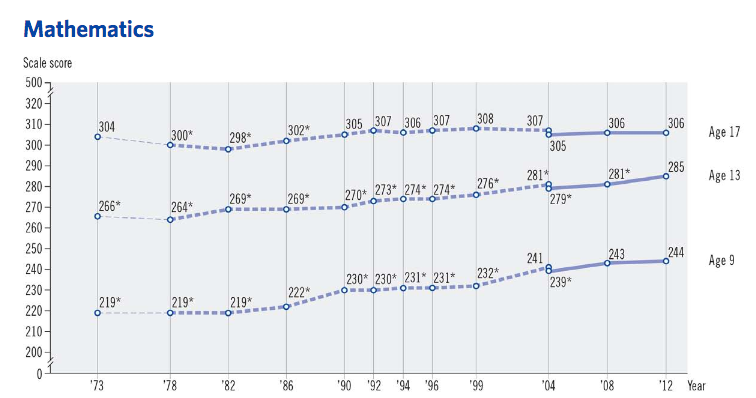

On the long-term-trend National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a federal test designed to measure progress over time, overall scores have gone up for reading and especially for math among 9- and 13-year-olds since the early 1970s. Results have been basically flat for 17-year-olds.

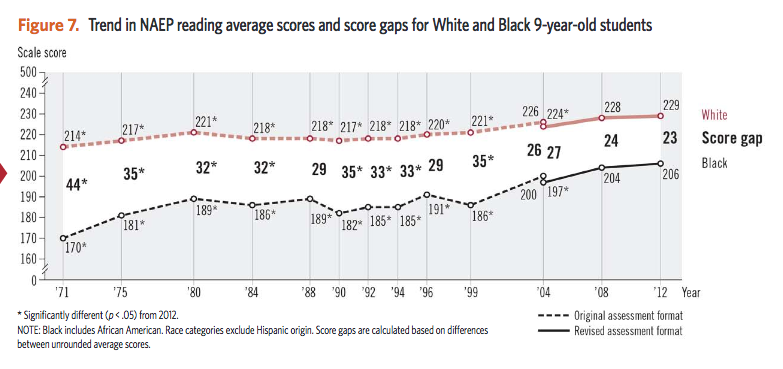

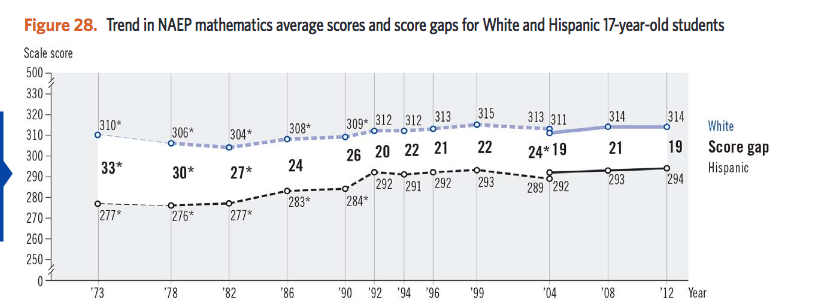

Gains are even more evident when disaggregated by race, while the racial achievement gap between white and black students and white and Hispanic students narrowed, often significantly.

Trends are generally similar on the main NAEP — increases in fourth and often in eighth grade; flat scores in 12th grade — though scores dropped slightly across the board between 2013 and 2015. (There are two NAEP exams: the older “long-term trend” test and the newer “main” assessment, which has existed since the early ’90s and is designed to reflect schools’ curriculum.)

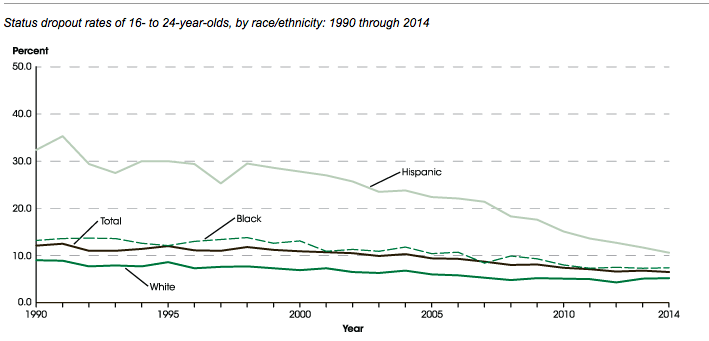

Meanwhile, high school graduation rates are up across the board — at an all-time high, in fact — and dropout rates are down significantly, especially for black and Hispanic students. However, some argue these rates may be inflated by schools’ lowering standards for graduation. For instance, a federal audit prompted Alabama’s state Department of Education to acknowledge December 8 that it had misreported its graduation rate, which showed a massive increase in recent years.

International scores paint a mixed picture of U.S. performance trends. On the PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) exam, which measures high schoolers on three subjects, performance is basically flat in science and reading and down somewhat in math since 2000, when the test was first administered.

Meanwhile, the TIMMS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study) test shows that American students have made large gains in fourth- and eighth-grade math and eighth-grade science since it started in 1995.

Gains on TIMMS, which focuses on earlier grades, but not PISA, which tests high schoolers, are largely in line with the trends by age and grade on NAEP.

Even decades ago, student performance on international exams was not particularly strong compared with other countries, according to an analysis by Keith Baker in Phi Delta Kappan. Notably, though, low-income students have made significant gains in math on both PISA and TIMMS.

In short, based on the available data, student performance has generally risen or held steady over time — meaning it’s very hard to make a case that schools can be returned to past “greatness.”

An important caveat is that educational performance does not just reflect schools: such data inevitably measure larger societal trends and out-of-school factors. It is difficult, even impossible, to know what share of gains in student performance may be due to — or even in spite of — schools.

Still, the data suggest that the burden of proof should be on those claiming school performance has dropped precipitously. If DeVos really believes that schools need to recapture their lost greatness, she is either mistaken or referring to something else about schools other than measured performance.

The Dick & Betsy DeVos Family Foundation provides funding to The 74, and the site’s Editor-in-Chief, Campbell Brown, sits on the American Federation for Children’s board of directors, which was formerly chaired by Betsy DeVos. Brown played no part in the reporting or editing of this article. The American Federation for Children also sponsored The 74’s 2015 New Hampshire education summit.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)