Before ‘Brown,’ the U.S. Had 100 Black Boarding Schools. Now, There Are 4

Piney Woods President William Crossley talks about the importance of Black institutions — and how his survived at the height of the Jim Crow era.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

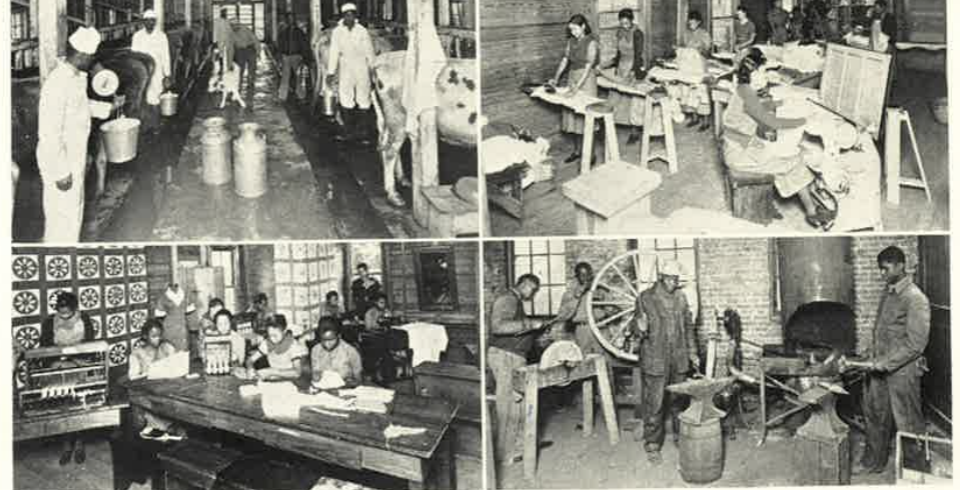

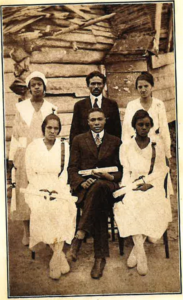

About 20 miles south of Jackson, Mississippi, sits one of the last Black boarding schools in the country: Piney Woods. Founded in 1909, the school was created for the illiterate children of poor Black sharecroppers with a focus on vocational learning. Its founder, Laurence Clifton Jones, came from Iowa to Mississippi with $1.65, looking to improve the 80% illiteracy rate in rural Rankin County. At the height of the Jim Crow era, Jones was nearly lynched by a white mob for starting the school, but he convinced them to spare his life, and some even donated money. For over 100 years, Piney Woods has been a pillar of support for marginalized students — particularly at a time when school segregation had a disparate impact on Black children. In 1940, Piney Woods expanded to allow blind students to fully participate, and it has received accolades from figures such as Helen Keller and former Rep. John Lewis. Notable graduates include the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi and the Cotton Blossom Singers. The school boasts a 100% graduation rate.

Piney Woods is a co-educational, Christian college preparatory high school. With over 2,000 acres of land, it has a 250-acre farm that its 100 students tend to daily while caring for the animals and learning about crops. Tuition is $45,000, though every current student receives at least some financial assistance. William Crossley, the school’s fifth president and the first to be an alumnus, spoke to The 74’s Sierra Lyons about Piney Woods’s survival and its parallels to his personal education journey.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Before Brown v. Board of Education, there were about 100 Black boarding schools across the country. What does it mean to you to be leading one of the last four that remain?

It’s an interesting thing that many of these institutions have sort of gone by the wayside. But in our case, we recognize that the challenge [of] providing high-quality educational opportunity for young people, particularly low-income young people and people of color — that challenge still exists for us as a nation.

Piney Woods has a 250-acre farm and over 1,000 acres of wildlife. What opportunities does the land allow for students to learn hands-on? What’s a typical student’s day like?

We say, “The campus is our classroom, the land is our lab.” Yesterday, we had students down on the farm caring for the animals. We’ve got eight horses, 60 to 65 head of cattle, roosters, chickens, goats, sheep and some farm dogs. There’s something about caring for animals, and there’s something about working with one’s hands, that connects to one’s brain.

We’re starting a farmer’s market here. The kids are helping to grow that, and we will teach them entrepreneurship. The kids have to sit down and do business and marketing plans. Those become part of how we decide what to sell in the market, which is on our campus. It’s not just for our young people, but it’s for our community, too.

We do study things in the history books, but we also go to the site of Emmett Till’s death here in Mississippi. We go to the Civil Rights Museum here, and we go to the preserved slave cabins on plantation land in Natchez. We go to Memphis and we see the hotel where Dr. Martin Luther King was shot and we go to the founding site of this institution and see where Lawrence C. Jones was brave enough to find a way to start this enterprise, and we’re all here because of what he did.

And so we literally live that history and we do it in science because we have five ponds on our campus. And so when we’re testing for bacteria, we’ll get the water out of the faucet, and then we’ll get the rainwater that made its way into the pond and our students will do comparative analysis on what’s in the water.

Historically, you will have seen pictures of a classroom in 1920 with the desks all lined up and the teacher in front of a blackboard. Then people show a similar classroom today with desks all lined up, with the teacher in front of the whiteboard. One of the things we try to do is break out of that to help our young people understand that to live is to learn and to learn is to live. We don’t make this distinction that you’re in school so you have to sit at this desk a certain way. Our students field calls at our switchboard, our students call our donors and thank them for supporting us with scholarship funds. They call admitted students and say, “Hey, I understand you’ve been admitted to Piney Woods. Well, I’m a 10th-grade student and we’ll both be together next year, and I wanted to see if you had any questions.” Our students go out and carry the message of this institution all over this state and nation, and so it really is learning practiced through living.

How did Piney Wood survive as all those other schools were closing?

One of the things is that we understood our mission, and we try to situate our mission and our vision in the period in which we live. Prior to Brown, Piney Woods issued associate degrees. Once the junior college/community college systems began to allow Black people to come, we recognized that the need was not as great. And so our program adjusted, and we stopped issuing associate degrees. It did not mean that the mission was not still viable. It’s no secret that you can pretty much track an individual’s educational progress by the income levels of their families. If you come from a family with a higher income, you’re that much more likely to succeed and have access to higher-quality education. Part of what we wanted to do was to ensure that we’re still addressing that challenge. You have to adjust to what’s happening in the world but still question what’s the relevance of your mission.

Piney Woods has had an alumni community that’s come forward to support its work and that sacrifices to make sure Piney Woods can still exist and do this work. Piney Woods has an independent board of directors. Sometimes these schools were run by churches, and they sort of went the way of the congregation or denomination and didn’t have as much control over how it advanced. Particularly during days of segregation, there were a number of these institutions that received state support because states didn’t want integration, so they would send some money to the Black boarding schools, which would essentially allow them to avoid integration. When the money left, these institutions couldn’t operate. Piney Woods operated independently of that for most of our existence. I think leadership matters. Piney Woods had strong leadership from our founder, but then we’ve had strong leadership from other folks who preceded me, and our goal from the start has been about building next-generation leadership in all that we do.

This month marks 70 years since the Brown v. Board ruling. Following the decision, many Black teachers and principals were dismissed. What generational impact do you believe this has had on Black students?

You know the old saying, “if you can see it, you can be it.” When Black males have one Black male teacher in elementary grades, their chances of success increase exponentially in school. To some extent, that was true for myself. I grew up on the south side of Chicago and I had teachers who were white, who were Black, but for the most part, they were female. I can remember one male teacher that I had along the way, but who was white, and then the folks in charge were typically white. We didn’t have Black models in leadership at the classroom level, or even at the local school level, and so we are pioneers. Piney Woods is by no means an all-Black staff. We have a diverse leadership structure here that I hope sets a standard for our young people to see.

Laurence Clifton Jones founded the school to educate the children of impoverished Black sharecroppers. With that history in mind, how has Piney Woods remained a safe haven for students who may have financial hardships or face other forms of marginalization?

This is near and dear to me because I will confess that there were moments when this institution faced financial challenges and some thought the answer would be to pursue more exclusively — essentially, people who could pay tuition. Lawrence Jones founded Piney Woods with $1.65. The ability to pay tuition has never been how we [decided] who would get this kind of an opportunity. Our board has worked diligently to ensure that we stay true to that from a mission standpoint. If you can afford to contribute more, we ask you to make a bigger contribution. But if a family doesn’t have the funds, no child is turned away for an inability to pay his or her way. Every young person who is here today has a scholarship. If there are folks who want to come and don’t want a scholarship, we welcome them, too.

The reason we can do that is that members of our community … we have something called the Circle of Faith that they sometimes will recommend a student and they will send contributions to help support that student’s education. Across this nation, the community of supporters makes this kind of work possible.

What does it cost to attend?

About $45,000 per student per year. That’s with room and board and really all their expenses. We don’t say if you want to be on the basketball team, you have to pay an extra fee. Once you’re here, you’ll be part of whatever’s happening, The National Association of Independent Schools pegs the cost of attending a boarding program like ours … we are 50% less than the average boarding school costs in this nation, and we successfully get all of our young people admitted to postsecondary options: community, college, college, military, etc.

You are the first principal to be a former student. How did your time as a student impact your view of education and opportunity in rural Mississippi?

My experience before coming here to Piney Woods was not a good one. I grew up in difficult neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago. My life changed when I came to this institution, and it took me some time to realize that. I was having leadership opportunities that I don’t know I would have ever had, had I stayed back in a public school at home. My grades and my GPA were well beyond where I would have been had I stayed home.

I got a chance to go to the University of Chicago as an undergraduate. We lived with my grandmother, and she lived about a 15-minute drive from the university. Nobody from our neighborhood went to the University of Chicago. I had driven by it my whole life but I didn’t even know it was a university. Nobody in my family had gone to college. Maybe my last year in high school at Piney Woods and my first year in college at the University of Chicago, it dawned on me that the people I grew up with didn’t have the opportunities that I had. I knew my cousins and folks at church. I also knew that I wasn’t as smart as some, I just had had an opportunity that they didn’t, because Piney Woods had given me that opportunity. I had really at that point in my life said, “This is unfair. It’s unfair for me to be at the University of Chicago and for my cousin to be in Joliet federal prison. That sort of ignited my passion to ensure that we were making educational opportunities available despite the accident of one’s birth, and that’s what this place has done for 115 years. And when I spend my life doing that, that’s the most fulfilling thing I can imagine.

Before returning to Piney Woods, you worked as senior adviser in the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education. What was your experience with returning to Piney Woods after having such an aerial view of education in the country?

I actually started my career in the classroom. I was teaching in Chicago Public Schools and was volunteering for a first-time-ever candidate for Illinois state Senate from our little district in South Side Chicago named Barack Obama, who went on to do some other things after he got into the Illinois legislature. So I started there and I became really frustrated with the bureaucracy. I wanted to find a path that I could make change on. I didn’t think I could do that with the 26 kids I had in my class, I went to law school, I ended up in a senior position working in government trying to change educational disparity, and Piney Woods sort of came along.

So I went from this space of working on policy to working directly with people. That was life-changing. I was no longer just putting a policy on the table — I was sitting across the table from a young person who was making a decision about whether to go to college or which college to go to. Or the young person who was sometimes making adult decisions about whether to even remain in school. In many ways, I went from a kind of work that felt very transactional in Washington, D.C., to work that I know is transformational in nature here on the ground. It’s been really a thrill and a delight, because I literally get to touch and sit and really know the people whose lives are being changed by the work we’re doing.

Piney Woods is 20 miles south of Jackson, in the state with the nation’s largest Black population. When policymakers and education leaders are discussing school choice, what specific needs for Black parents and students in the rural South do you believe should be considered?

When I was in D.C., my daughter was on a soccer team, and they lost every game. Sometimes they just lost because the other team had superior skills. But many times they lost 1 to 0, and the one goal the other team made sometimes had gone in accidentally. The reason the ball was able to go in accidentally is because it consistently was on my daughter’s team’s side of the field, which meant that they were always on defense. Another person could, just by sheer luck, put points on the board.

I think that Black kids growing up in America often live their lives on defense. The expectations of them are low. When a Black child fails in school, nobody’s surprised, and that’s a problem. This place changes that. We say this is where you belong, that we expect you to excel and to achieve, and you’re not going to live life on defense. Quite the contrary. We expect you to put points on the board.

One of the things we offer is an atmosphere that says you’re a part of this community. You’re a part of, dare I say, this family. Just as my two daughters aren’t allowed to say, “I can’t do it,” neither are you. There’s a whole field of scholarship from Tocqueville on the impact of community and advancing and turning around its members. The solutions often live on the ground in the community. I think we can choose whether to subject our kids to a mass-production factory model, one-size-fits-all notion of learning, or a personalized, culturally supportive environment in which every single young person is expected to achieve in their own right. I think we do the latter, and we’ve had success, certainly for my 10 years, but for 115 years. I hope that serves as a lesson for us as a nation about the kinds of spaces we should make for the best learning outcomes for young people.

When the time comes, how do you hope to leave the school better than how you found it?

This place was started in the middle of nowhere with almost nothing but a burning desire and passion to have an impact on the lives of others. People invested in that and it came to fruition. Lawrence C. Jones, our founder, described it as “a resistless urge to help people build better lives for themselves and their communities.” I got to be here because people who didn’t know my name, and long before I ever got [here], invested in this space on the belief that someday somebody like me might come through.

I tell our students it so deeply humbles me to think that our enslaved fought for freedom that they never would personally realize, but they fought for those freedoms for future generations and people invested in me in ways that I can’t fully measure. I hope that someone will say, “He did his absolute best to pay it forward, that he did his absolute best to ensure that this institution would become a regenerative community that gives more to the world than it ever takes from it.” If we can position this work to go out and have that kind of an impact, then I think we will have done our work well.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)