Baron: ‘Boring!’ Is How Students Describe Reading on Screens. To Reengage Them, Schools Must Bring Back Print and Move Away from Digital

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As schools strategize their fall opening, COVID-19 challenges are never far from the classroom door: Will in-person classes be safe? What if schools need to pivot back to virtual classrooms and overwhelmingly digital learning materials? But another challenge also belongs on schools’ planning radar: How to regain a balance between digital and print reading.

New research underscores the critical role of print in students’ own eyes, especially given their prolonged slog with distance learning because of the pandemic. After so much enforced reading on screen, students’ perspective about digital reading can be summed up in one word: boring.

For many years, researchers have compared students’ comprehension when reading in print versus on a digital device. (Bottom line: With linear, informational text, print scores are higher.) Yet students also have much to say about their learning process. Research that my colleagues and I did at the secondary and university levels demonstrated students’ strong beliefs that they concentrate — and learn –—best with print. However, we are a technological society. Digital reading in education has become increasingly common and will remain so. But the pandemic has stretched the bounds.

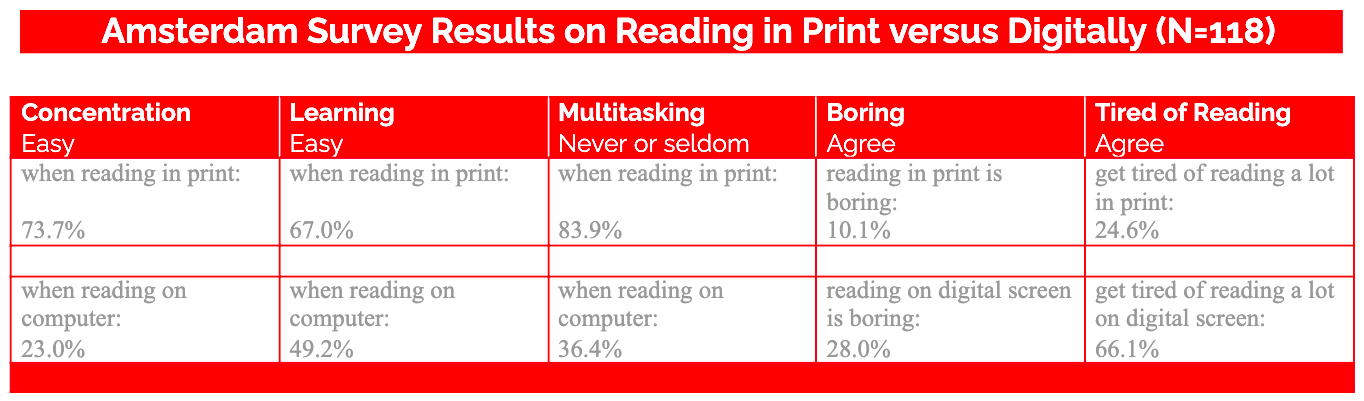

Collaborating with my colleagues Anne Mangen in Norway and Kim Tyo-Dickerson and Frank Hakemulder in the Netherlands, we surveyed 118 middle and high school students at an international school in the Netherlands this past spring to gauge the impact of intensive digital reading during the pandemic.

We asked these students’ about their ability to concentrate and to learn when reading in print versus on a digital platform. As with our prior surveys, the students from Amsterdam clearly judged their concentration and learning were better with print.

But this time, we probed an issue that had bubbled up in open-ended comments, especially from secondary school students, in our earlier surveys: the extent to which each particular medium was entertaining or boring. Our aim was to assess how and whether all the digital reading during the pandemic was influencing students’ perspectives.

According to our research, which has not yet been published, the answer was a resounding “yes,” and not in a good way. When we explicitly asked the Amsterdam students if they felt reading in print was boring, 10 percent agreed. But when asked whether reading on a digital screen was boring, nearly three times as many — 28 percent — said it was. Additional questions reflected the same lopsided assessment. While roughly 25 percent agreed they got tired of reading a lot of print, the response jumped to 66 percent for reading on a screen. What’s more, when we asked the group what they liked most and least about reading in print and reading digitally, no one wrote that reading digitally was entertaining. (This is a change from prior surveys, where some students volunteered that reading digitally was entertaining.)

The reason these new findings should alarm educators is that if students are bored, they’re not concentrating. And if they’re not concentrating, they’re not learning. Given the overwhelmingly digital learning environment during the pandemic, these results should not be surprising. Screen fatigue is real.

Equally real are the learning losses children have suffered, including in reading. A recent Stanford University study found that second- and third-graders lagged about 30 percent behind the reading fluency gains they would have made in a normal academic year. A Dutch study of 8- to 11-year-olds revealed learning losses in math, spelling and reading comparable to about one-fifth of a school year.

The causes of this learning loss are complex, running the gamut from lack of social contact to inadequate home learning space or internet access. But a persistent theme we cannot ignore is the reading platform.

Reading digitally can be challenging, especially with material calling for mental focus. We are apt to read electronic texts more quickly (even sometimes assuming digital is somehow shorter than the print equivalent). We slip into a shallow reading mindset, of the sort reasonable for perusing social media status updates but not for careful analysis. And we are far more likely to multitask. In the Amsterdam study, 84 percent of students said they seldom or never multitask when reading in print. When reading on a computer? A sparse 36 percent reported they avoided multitasking. If you’re multitasking, it’s hard to concentrate or learn.

As the new school year opens, schools need to find ways to harness the lessons students are teaching about reading platforms and learning. Obviously, both print and digital have their strengths. The problem is that because of the pandemic, the mix became badly skewed. It’s up to us to redress the balance.

When in-person learning is possible, schools should strategize where to reintroduce print, especially in contexts in which it’s important for students to take their time, to reread, to analyze, to make connections, to imagine. Should concerns about the Delta variant drive students back to virtual learning, this time, schools must get some print materials into their hands before sending them home. Parents who choose to homeschool their children need to be made aware of the pros and cons of print versus digital reading.

The school year ahead will demand adaptability and creativity in the face of evolving unknowns. But amid these uncertainties, there is an opportunity to build upon the clear message students are sending about how they learn when reading. By listening to students, we’ll get through this together.

Naomi S. Baron is professor emerita of linguistics at American University and author of “How We Read Now: Strategic Choices for Print, Screen, and Audio.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)