Barnes: Indianapolis Consolidated Everything But Its Schools — Leaving 11 Different Districts Where Black Children Are Often Left Behind

When I meet people who don’t live in Indianapolis, where I was raised and attended school from K-12, they assume the only district in Indy is Indianapolis Public Schools. This is not true.

Within the boundaries of Indianapolis are 11 different school districts. The 11 school districts were a result of Unigov. Unigov was a 1970 effort to consolidate resources and incorporate towns into the city of Indianapolis to help stabilize and grow the city. To ensure the merger would pass, politicians allowed existing school districts to retain their autonomy and not consolidate into one school district for the city of Indianapolis.

There are two main viewpoints typically shared in Indy to explain why schools were excluded from the merger. Chalkbeat Indiana highlighted one viewpoint in the article “How racial bias helped turn Indianapolis into one city with 11 school districts.”

Indianapolis was not the only city in the country to merge with its surrounding county at that time — but it was the only one to explicitly leave schools out of the deal … The judge who ordered the (desegregation) busing, Samuel Dillin, stated bluntly that a merged city that left 11 separate school districts was racially motivated at a time when a majority of the region’s African-American and minority students lived in the city center while the surrounding school districts primarily enrolled white students.

The Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township Superintendent Dr. Jeff Butts, who recently was named Indiana Superintendent of the Year, shared another viewpoint about Unigov in an interview published by The Educator’s Room.

When we had Unigov under then-Mayor Lugar one of the things they tried to tackle was the school districts, but the local boards and the local community said we are not going to allow that to happen. Unigov was successful to some degree but it did not consolidate all services in the city of Indianapolis. When you think about the individual school districts in Marion County, every one of them has their own unique footprint in our community. I think to some degree each one of those townships reflects the community in which it is located which is part of the reason those communities didn’t want to consolidate.

I believe both viewpoints are correct. People liked their schools the way they were. They did not want them to change, and racism was a factor. Let’s not forget the Ku Klux Klan’s long presence in the state of Indiana. A high school was built in Indianapolis, Crispus Attucks, solely for black students to attend. White people were so adamant about not integrating, they built black students a school. Many decisions that have been made to improve Indianapolis have hurt black children, and that hurt begins in the schools.

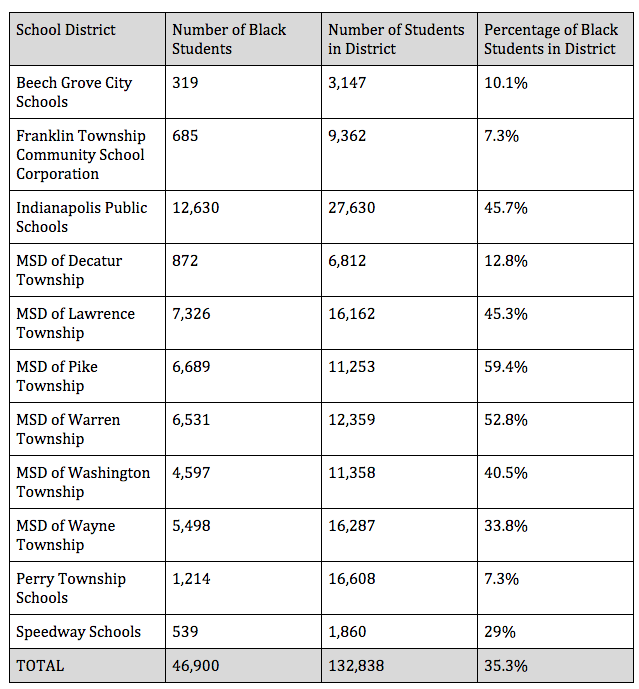

According to the most recent data available from the Indiana Department of Education, here is the number of black students in each school district in Indianapolis.

Some months ago, I asked a local publication why they don’t cover stories about students in the other districts as much as IPS, and the reporter told me they had limited resources and had to focus on the biggest school district in Indy. The same problems reporters frequently highlight about children in IPS, such as teacher turnover, high numbers of minority students being identified for special education, and lack of teachers of color, to name a few, are the same problems found in other school districts, and these problems hurt black children. When no one is talking about it, problems fester and some might assume no problems exist. Because black students are divided among multiple school districts, many of them are left out of the education conversation. When I watch the news on TV, read the newspaper, or read an article online, the focus is mostly on Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS). Yes, IPS has the largest number of black students, but the majority of black students in Indy attend a school district that is not IPS, and you rarely hear what is happening to black children in those districts. Black families know what is going on in the 10 other districts; we always have, but hardly anyone will listen and highlight those concerns.

The Metropolitan School District of Washington Township spans the northwest and northeast side of Indianapolis; it is where I live and my children attend school. District officials publicly acknowledged they had way too many black children identified as needing special education and had way too many black children being sent out of class. When I talk to other black parents in the district, many don’t know about this.

During the Jan. 11, 2017, board meeting, the following summary was provided about information the district’s director of special services, Mary Lowe, presented to the school board during the previous board meeting on Wednesday, Dec. 14, 2016:

Mrs. Lowe reported that our school district has a significant rate of disproportionality of African American students being placed in Special Education. The District has hired a consultant to help with this disproportionality issue. Mrs. Lowe and the consultant will work with every principal to ensure that students are being appropriately placed. She also stated that there are many things being done correctly, however, there is still room for improvement.

There wasn’t a news article published (not to my knowledge) to share information with the public, but if it were IPS, it might have made front-page news. Yes, I’m aware that some issues are listed in board reports that are available to the public, but how many black parents actually know how to access them? Specifically, Lowe shared the following about the district’s work with consultant Dr. Renae Azziz, founder and director of Virtuoso Education Consulting:

Assistant principals are also working with Dr. Azziz to operationalize our discipline referrals so we have a common understanding about what constitutes an infraction. For instance, what does insubordination mean? So we got some language for everybody to have some consistency. She felt that our behavioral RTI (Response to Intervention) system is very weak across all buildings so we are going to work towards the development of a more effective process for tiered response.

I do give Washington Township credit. Not only did the district identify the problem, but they also had meetings, collected data, distributed surveys, implemented culturally responsive professional development, and updated the discipline code. But as a resident of this district, I only found out about this situation through some work I do with a few local committees.

I still don’t know how or if the work with Dr. Azziz improved the situation. I still wonder how big the disproportionality gap is. When people don’t even know there is a problem concerning children who look like their kids, they are not able to lend their voice to the conversation. I wonder how many parents whose black children were excluded from class were able to give feedback.

I know my son was once disciplined for being disrespectful. When I asked what he did that was disrespectful, the teacher stated, “He was standing beside the line and wouldn’t get in the line when I asked him.” Yes, my child should have followed the directive, but was discipline really necessary? My personal experiences and the experiences of other black families is why I am concerned about the well-being of black children across the city of Indianapolis.

Back in January, I was at the statehouse hoping to give testimony in support of House Bill 1421 School Discipline. This legislation would require that each Indiana school’s discipline plan contain evidence-based discipline practices. People for this bill, like myself, were hoping this legislation would force schools to move away from zero-tolerance policies, which would help address disproportionality in discipline rates between white students and students of color. This issue of students of color being subjected to harsh discipline at rates greater than their white peers is a national problem, but it’s particularly stark in Indiana. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights School Discipline Issue Brief released in March 2014, “Indiana was one of five states that reported male suspension rates higher than the nation for every racial/ethnic group and one of eleven states that reported higher gaps than the nation between the suspension rates of black students and white students for both boys and girls.”

After hours at the statehouse, Rep. Robert Behning, chairman of the House Education Committee, called a recess after one person gave testimony for the bill. What I found interesting were the conversations I heard from people opposing the bill in regards to black students before the session began. Specifically, they were speaking about the effect this bill would have in Beech Grove Schools and Speedway Schools.

They felt schools should decide what should happen and that there didn’t need to be a law. They also explained that if, hypothetically, 90 percent of black students had discipline problems and it was highlighted, it would make the district look bad because the 90 percent could be nine black students out of only 10 total. Maybe they believe their time would be better spent on the largest racial group in their district, white students (in Beech Grove, 71.4 percent, and in Speedway, 45.3 percent), because the discipline issues of a smaller racial group, their black students, isn’t a good use of their time. These are the conversations some people in power in districts outside of IPS are having. As a black educator and parent sitting in the room hearing this conversation, I was enraged and concerned.

Because I was adamant about my testimony being heard by lawmakers, especially after hearing these alarming conversations, I returned to the statehouse a second time to give my testimony. After waiting for 4½ hours, I was able to speak to Indiana’s lawmakers. The bill did pass and was signed into law earlier this year by Gov. Eric Holcomb. Although I’m glad the bill became law, it had some amendments added as it made its way through the Indiana House and Senate: “The DOE may not require or pressure a school corporation to adopt any aspect of the model plan. Also, The DOE cannot conduct reviews, other than any reviews the department currently conducts, of school discipline plans.”

I find these amendments concerning because a school could still be compliant by law and adopt a plan, but it might not be the best plan, and the Indiana Department of Education can’t even go and conduct a review to specifically see how the plan is being implemented.

This is why I am pro-school choice. People many times ask why I’m for private, parochial, charter, traditional public, and homeschooling — I do have reservations about online schools. I’m pro-school choice because there are limited options for black children. As an educator, I am frequently asked by people in the black community which schools are good or which school districts are good. When people ask that question, what they are really asking is, “Shawnta, will my black child be OK at this school?”

Unfortunately, it comes down to each individual school, the leaders in those schools, and the teachers inside the school walls. I am a proud resident of Washington Township. If you would have told me that one of my twin sons’ teachers would frequently be absent, kick him out of class when she bothered to show up, and then quit after winter break, I probably wouldn’t have believed you. Even though my sons’ school is in a good community and has a strong principal, he still ended up with a teacher who didn’t know how to work with children of color.

Indianapolis has an interesting educational landscape because we have choice on top of choice. We have charter schools; we have a large school voucher program, which allows impoverished children to attend private schools; and we have school districts like the MSD of Washington Township and the MSD of Wayne that let out-of-boundary students attend their schools. When I participate in education conversations and I hear people try to explain to me how charter schools are privatizing education or that private schools are stealing money that should go to traditional public schools, I see real faces.

I see my cousins’ kids, my neighbors’ kids, and my friends’ kids who are benefiting from choice in Indianapolis through attending a school district out of boundary, attending a charter school, or attending a private school using a voucher. The alternative would be to let those children stay in their boundary’s failing schools, and there are failing schools in Indianapolis that exist outside of IPS.

If these so-called education advocates really wanted to fix education, they would start by improving the schools black families are fleeing. That would mean acknowledging the problems that black children face in all of the 11 school districts in Indianapolis, but I guess ignoring the problem and the faces of black children is easier.

Shawnta Barnes is an elementary library/media specialist for the Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township in Indianapolis and an adjunct professor at Marian University. The married mother of identical twin boys, she often writes about education in Indianapolis.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)