Remarks prepared for the 2016 Global Google Education Symposium

This is an iconic photograph of St. Paul’s Cathedral, taken in 1940 during the Blitz when London was bombed for 70 consecutive nights.

The picture above had huge emotional resonance for my parents’ generation; as young adults they lived through that year when Britain was alone, fighting fascism.

Here is a similar view of St. Paul’s at the end of the war, surrounded by the rubble of destruction.

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

This was the view my mother saw each morning as she crossed Southwark Bridge on her walk to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, where she was training to be a doctor. She found the sight of St. Paul’s rising majestically above the city very inspiring. Millions of Londoners felt the same way. St. Paul’s was still standing. Britain had endured.

This would have pleased the man who designed St. Paul’s, Sir Christopher Wren, one of the finest architects in Britain’s history, who claimed that it was “built for eternity.”

In medieval times, a very different cathedral, the old St. Paul’s, had stood on the same location.

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

A classic Gothic cathedral, impressive its own way, it had, over the centuries, become dilapidated. In the 1560s, its tall spire was destroyed by a lightning strike. A century later it had still not been repaired.

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

After the trauma of civil war in the mid–17th century, the newly crowned king, Charles II, wanted a capital city to be proud of, and the battered cathedral didn’t match his ambition.

In 1663, Charles II instructed his surveyors to assess the state of the old St. Paul’s. After a thorough examination, they recommended that the existing building be repaired; no alteration was needed to its general form and structure. They could re-clad it, patch the steeple and renovate the portico. In short, their conclusion was patch and mend. This way forward had the added virtue that it would cost much less than a new building, no mean consideration for the cash-strapped monarch.

Sir Christopher Wren, who was a member of the surveyors’ group, had a different view. Still in his early 30s (and already renowned as a brilliant scientist, mathematician and inventor), Wren produced what we would call now a minority report.

The old cathedral had been “ill-designed” and “ill-built,” he said. It wasn’t just decrepit, it was fundamentally flawed. Its steeple was “a heap of deformities,” and the whole building was “too narrow for its height.”

Given these problems, why patch and mend it? Surely, he thought, a grand and new cathedral would best represent the restored monarchy. He had been studying domes and was enormously impressed by drawings of Hagia Sofia in Istanbul, the magnificent edifice that even at the time had stood for more than 1,000 years. His conclusion was clear: the King should commission a new cathedral with a “noble dome.”

The King and his advisers admired Wren, but the conception seemed radical, too ambitious and expensive. Patch and mend won the day.

Three years later, the Great Fire came to London, starting in a bakery on Pudding Lane and driven through the city by a fierce wind. On Sept. 2, 1666, the diarist Samuel Pepys wrote, “We beheld that dismal spectacle … the whole city in dreadful flames.” The next day he concluded, “London was but is no more.”

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

The city was in ruins, and the old cathedral was irreparably damaged. Charles II had no choice. London could not be a great capital city without a great cathedral.

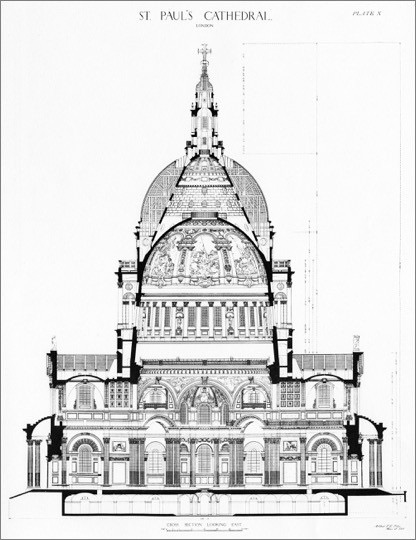

This time Sir Christopher Wren would be in charge. He designed and went on to build the wonderful domed cathedral that survived the Second World War and still stands majestically in the heart of the City of London.

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul’s Cathedral

St. Paul’s has rare grandeur seen from the outside.

Photo: Graham Lacdao, St. Paul’s Cathedral

And inside, what is so striking is its nobility, its perfect proportions and, not least, the light.

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul's Cathedral

Photo: Courtesy of St. Paul's Cathedral

Wren gave the new cathedral, built for eternity, and indeed for the entire rebuilt city, a Latin motto: “Resurgam,” risen again. It was not forgotten in 1945 when, once more, London rose again.

Here is another city devastated by a different catastrophe: New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. It too needed to rise again, and, in education at least — this is an education conference, after all — it most certainly has.

Photo: NOAA Office of Response and Restoration

Thankfully such catastrophes — whether fire or flood — are rare. But for leaders of education systems, whether in this room or elsewhere across the world, the dilemma of St. Paul’s or New Orleans is constant: patch and mend or transformation?

Look at some statistics that represent the state of global education. Let’s start here in America.

- One in every three black men in America will go to prison; just one in five receives a bachelor’s degree.

Patch and mend or transformation?

My own country, the United Kingdom, has its own challenges.

- In 2012 in England just 40 students on free lunch were admitted to Oxford or Cambridge; 82 students were admitted from Eton College alone.

Patch and mend or transformation?

Europe has major challenges too.

- Youth unemployment in Greece is 50 percent. It is not much better in Italy or Spain.

Patch and mend or transformation?

And in the developing world the challenges are greater still.

- 78 percent of the population of Uganda are under the age of 30, yet a recent newspaper headline in Kampala proclaimed:

Photo: Courtesy of The Daily Monitor

That’s teachers. Imagine what that implies for literacy and numeracy among the country’s children.

Patch and mend or transformation?

Even if every system were already working well — which is clearly not the case — the challenge ahead would be huge because the world is changing so radically and rapidly.

- 47 percent of U.S. jobs, it is predicted, are at risk from automation in the next decade or two.

Patch and mend or transformation?

Of course, marginal improvements year-on-year are worthwhile, but, with education systems in both the developed and the developing worlds underperforming and, in some places, catastrophically failing, with dramatic changes in the world around us driven by globalization and technology, and with global geopolitics more uncertain than at any time in my adult life, why so often do we reject transformation and choose patch and mend?

There are many reasons. One is cost — though patch and mend is in fact very expensive in the long run, especially if all it does is replicate endemic failure, it is much cheaper in next year’s budget than transformation — and all too often short-term pressures override long-term aspirations.

But cost is only one reason — and not the most important. As every education reformer knows, the biggest challenge is to take on those entrenched in the status quo. Take one example. For much of the 20th century, teachers unions were often aligned with radicals and reformers. So far in the 21st century, with the occasional notable exception, they align themselves instead with the defenders of the status quo, usually advocating more pay for teachers, smaller classes and less accountability. In short, they advocate the past, not the future. As a result, costs rise and performance stays flat.

Then there is the psychological barrier. Attempts at education reform have failed so often in the past (defeated by resistance, perhaps, or fatally undermined by poor implementation) that all but the most courageous education leaders are tempted by eye-catching initiatives rather than comprehensive whole-system reform. In these circumstances, the debate about education all too often becomes tired and worn — as resisters of reform point out all the problems of even attempting it and reformers find themselves compromising rather than facing the inevitable conflict. But compromise has its own cost. If it goes too far, nothing much changes and the case for the status quo is strengthened by default.

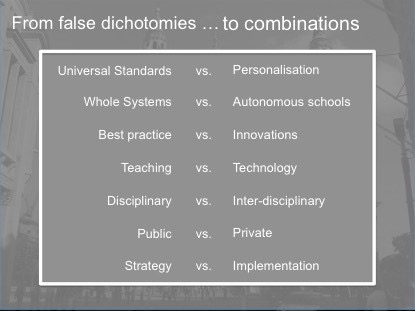

A manifestation of this process, peculiar perhaps to education, is debate as vigorous as it is unnecessary. I often say, the road to hell in education is paved with false dichotomies. Look at this chart:

In every case, the answer is not either/or; it is both/and. The interesting questions from a practical, reforming point of view are not which to choose but what combinations will maximize impact.

Then there is one final barrier, one that Christopher Wren overcame with his magnificent drawings of the future St. Paul’s, and that is a lack of imagination. We cannot build what we cannot imagine. It may be hard to imagine new buildings. It is harder still to imagine radically different school systems. Yet four fragments of a radically different future are there already; some schools and some school systems are already showing the way forward. For all these reasons, we flinch from taking bold decisions. What it comes down to ultimately is a lack of courage.

A few systems and system leaders have shown the necessary courage: Paul Pastorek and Paul Vallas in New Orleans after the flood; Tony Blair and his team in London in the early 2000s; Lee Kuan Yew and his successors in Singapore after independence in 1965; Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif in Punjab since 2011. None of these reforms is perfect, but each has dramatically improved student outcomes within three to five years. And in each case, early success has been built on productively.

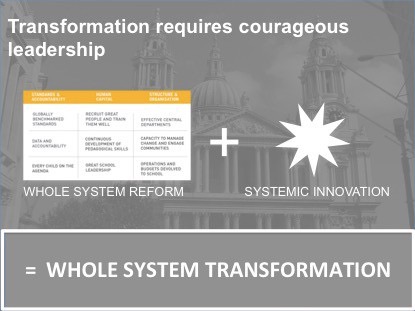

What is it these leaders are doing? Of course, each place has its own unique story, but there are common themes to draw out. Courageous leadership is a necessary precondition, but even the most courageous leader needs an evidence-informed reform design, the architect’s drawings.

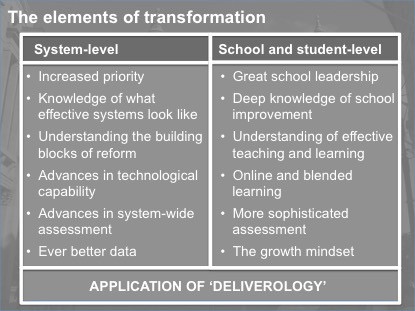

These combine two elements, as set out in the diagram below.

The courageous leader needs to avoid one final false dichotomy: When some advocate whole system reform and others innovation, the courageous leader needs to demand a judicious combination of the two.

Helpfully, we can spell out what this looks like on the basis of evidence. This is not the place to go into detail, but it is possible to summarize the system-level and school-level elements of transformation. The chart below summarizes the evidence.

Given the knowledge we have, given the new understanding that all children and young people can progress and achieve — the growth mindset — and given advances in data and technology, we should be on the brink of achieving dramatically improved educational outcomes, but to do so we must stop tinkering about with “initiatives” and seek transformation.

Of course, the design — the architect’s drawings — need to be combined with systematic implementation, what the chart above describes as “the application of deliverology.” Charles II was not always a wise king, but in appointing Sir Christopher Wren as both architect and project manager of the new St. Paul’s, he knew what he was doing.

I’m 61 years old now; assisting governments with the implementation of transformation is how I want to spend my time in the future.

It took 40 years to build the new St. Paul’s. Amazingly, Christopher Wren lived to see his cathedral, with its noble dome, completed.

You may have hoped for answers from me this morning; I have only questions.

Could we complete global education transformation faster than Christopher Wren built St. Paul’s?

Have we got 40 years? Have we? What do you think?

And that leaves just my fundamental question: Why do we have to wait for the fire?

Michael Barber is the chief education advisor to Pearson, the author of How to Run a Government (2015) and the chair of the WEF Global Agenda Council on Education.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)