Bankert: If Rahm Emanuel’s Graduation Plan Is to Succeed, Colleges Must Lower Barriers for Poor, Minority Students

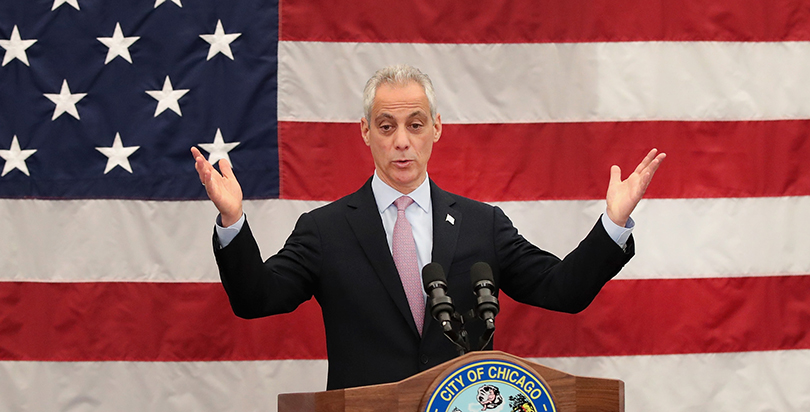

When Mayor Rahm Emanuel announced a new graduation requirement for Chicago Public Schools students last month, the reaction from detractors was swift. All Emanuel wanted students to do was provide a plan for their postsecondary education: an acceptance letter to a university, community college, technical school or apprenticeship, or the military. Yet his critics accused him of false optimism that the district would be able to give students the right supports — or quality education — to effectively navigate this requirement.

The detractors mostly miss the point — and inadvertently make Emanuel’s point about the absurdly low expectations we have for poor and minority students in Chicago. But while the mayor’s plan is well-intentioned, because it sends a clear message to students that high school graduation is not the end of their education, it ignores the reality that too many postsecondary institutions are fundamentally unprepared to see students, especially first-generation college-goers, through to a degree. That problem includes the schools Chicago students are most likely to attend and reveals a weak underbelly to the mayor’s vision.

Today, about 9 percent of low-income students earn a bachelor’s degree by age 24. That compares with a 77 percent completion rate for students from the top one-fifth of American household incomes. In the City Colleges of Chicago system, which serves 120,000 students across seven campuses, four of the colleges have graduation rates under 10 percent, and two others hover nearby. For those students who do graduate with a certificate or associate’s degree, more than one in five are not able to secure employment within a year of completion.

Many barriers hold low-income students back from postsecondary success. First is the academic: simply being unprepared for the rigors of postsecondary learning (which is largely on districts to address). Second is the financial and logistical: everything from covering the cost of attendance to physically being able to get to class to limited course selections that force trade-offs with work schedules. Third is the cultural or dispositional: lack of the postsecondary mindsets and stick-to-itiveness that can propel students over even the most daunting of challenges.

The schools are not set up to help address any of these barriers — frequently, they exacerbate them.

Bright spots do exist. There are a number of high-quality organizations, such as OneGoal, Bottom Line, and Beyond 12, working to get low-income students to and through college, with persistence rates many times as high as national averages (even for students with “average” academic profiles). And there are many districts and charter networks that have invested significant resources — college counseling, postsecondary partnerships, and alumni outreach coordinators — in successfully supporting their students through a variety of postsecondary pathways. Still, the missing link is often on the institutional side. Students enroll, but they then fall through the cracks with legacy organizational structures and policies that make it challenging for them to persist.

With this in mind, the mayor shouldn’t back down. Instead, he should do more by creating a mechanism for shared accountability for postsecondary success and taking the onus off students alone. Here’s one idea: The mayor could call for a diagnostic evaluation and overhaul of local institutions that attract a critical mass of local students, to help them change their practices to be more favorable and supportive of first-generation college-goers. This would require a review of the institutions’ student-facing policies and requirements (everything from course selection to master scheduling), availability and access of resources such as counselors and mentors, and educator mindsets and preparedness in shepherding students through an unfamiliar experience. It would also suggest a close look at the availability, accessibility, and consistency of data to help the institutions identify and respond to early-warning indicators such as low midterm grades or dropped classes. All this, of course, should be done in partnership with Chicago Public Schools, which should keep its foot on the gas of academic preparedness.

Although there are no established playbooks, City Colleges can learn a lesson from Georgia State University and its two-year affiliate, Perimeter College, which has invested in studying the barriers holding its students back and then systematically changing its practices. Student success initiatives have ranged from academic and financial counseling to small grants to peer tutoring and more. Taken together, these have increased Georgia State’s graduation rate for first-generation students by over 30 percent since 2010 — and the numbers continue to rise.

Yes, the mayor’s critics are lowballing Chicago’s students. But the mayor shouldn’t make the opposite mistake by setting them up for failure. His plan is a step in the right direction, but only part of the solution. Here’s hoping he seizes the opportunity to do more.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)