Philadelphia

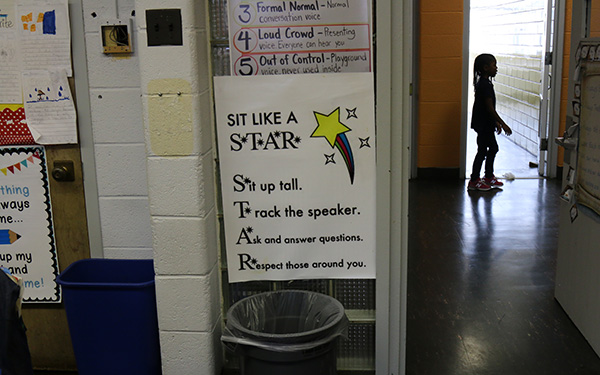

At John Wister Elementary School in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood, children come to class wearing matching polo shirts. In the hallways, students walk in straight, silent, and orderly lines. In the classrooms, signs instruct children to sit “like a S.T.A.R.” — meaning “Sit up tall,” “Track the speaker,” “Ask and answer questions,” and “Respect those around you.”

In one classroom, a teacher’s math lesson comes across as a rapid-fire combination of instruction, refocusing, and admonishment for improper behavior: “So, we can separate the numbers, we can add the 10s and the 1s, what else did we learn about? We’re not playing with shoelaces; put your hands in your lap, please, thanks so much. What is another way we learn?”

Until last year, Wister’s students had never experienced this degree of structure in their school. But when the children returned to the old brick building in August, the floors had been cleaned of years of dirt and filth. A fresh blue hue had replaced the monotonous beige walls. A putrid odor had been scrubbed from the bathrooms. The students were the same, and the building carried the same name. But every teacher and administrator was new.

Wister had been taken over by Mastery Charter Schools, the city’s largest charter network, which made its name turning around some of the city’s most hardscrabble schools.

“Many of our students start really far behind, and so the school needs to be just outstanding in providing many different types of supports to students and have an overall patina of high expectations,” said Scott Gordon, Mastery’s founder and CEO. “We, as an organization, have to firmly establish we believe every child in this school can succeed. We believe this can be a safe, productive school community.”

Unusual among charter networks, Mastery specializes in district school restarts, considered the most difficult model for improving persistently low-performing schools. Normally, charter schools start small and scale up over time, adding one grade per year and inculcating a culture of academic achievement in their students from a very young age.

A paper sign in a Wister Elementary School classroom reminds students to “Sit like a S.T.A.R.”

Not with restarts. Under Philadelphia’s restart model, launched in 2010 as the Renaissance Schools Initiative, charter operators are handed the reins at long-struggling schools with the expectation that they will raise achievement among students who are already enrolled.

That means dramatically changing the culture at schools that have been failing for decades. At Wister, for example, where 95 percent of the students are black and 71 percent come from low-income families, test scores have lagged for years. Just 4 percent of third-graders were proficient in math in 2016.

Mastery is “the best in the country” at turning around the lowest-performing schools, said William Hite, superintendent of Philadelphia’s public school district — where overall, just 32 percent of students were proficient in English last year and only 18 percent were proficient in math. In part, that success is a result of the network’s intent focus on school culture and climate.

“Nearly all Renaissance schools have shown a decrease in serious incidents and offender rates since they entered into turnaround,” Hite said. “So the climate of those schools are better, and the changes in school climate also appear to be correlated with changes in student achievement.”

But now, Mastery is undergoing a culture shift of its own.

Rapid improvement

Gordon founded the charter organization that would become Mastery in 2001 and by 2007 was running three troubled city middle schools at the district’s request. When Philadelphia launched the Renaissance initiative, Mastery’s turnaround work was given a bigger platform. Today, Mastery runs nine of the city’s 21 Renaissance schools, as well as nine Philadelphia schools not in the program. The network serves more than 10,000 students in the city — about 87 percent are African-American, 86 percent are from low-income households, and 17 percent qualify for special-education services.

Lori Shorr, an associate professor of urban education at Temple University who was former mayor Michael Nutter’s chief education officer, recalled visiting the Shoemaker Middle School campus in West Philadelphia before Mastery took over in 2006. Considered one of the city’s most violent schools, Shoemaker had kids wandering the hallways, skipping classes, and running amok, she said. Just 30 percent of the school’s eighth-graders scored proficient or above in math.

But near the end of the school’s first year under Mastery, she visited again — and experienced a drastically different vibe. The kids had been given a different set of expectations, Shorr said, and the results of the culture shift were apparent: Eighth-grade math performance at grade level jumped to 63 percent.

Rapid test score gains were seen at other Mastery Renaissance schools as well. In the 2010–11 school year, Mastery was given control of three elementary schools: Harrity, Mann, and Smedley. Within two years, third-grade math scores at Harrity jumped from 45 percent proficient to 60 percent. At Smedley, scores rose from about 51 percent to 57 percent. At Mann, scores increased from about 67 percent to 81 percent.

The schools saw similar growth in state reading scores. In two years, third-grade proficiency rose from 34 percent to 42 percent at Harrity, 56 percent to 69 percent at Mann, and 35 percent to 49 percent at Smedley.

In 2010, the network even came to the attention of then-President Barack Obama, who gave Mastery a shout-out in a speech and hailed its students’ rapid academic improvement as proof that struggling schools can rebound with the right supports. Obama highlighted results at Pickett Middle School, where student math proficiency jumped from 14 percent to almost 70 percent under Mastery in just a few years. At the same time, he noted, school violence dropped by 80 percent.

But in 2014, everything changed. Pennsylvania adopted new exams that aligned with the Common Core State Standards, and though Mastery’s schools held their own in English, math scores plummeted — even more dramatically than in the city district overall. For Gordon, it was a wake-up call.

No excuses

Early in the network’s turnaround work, Gordon’s schools adopted a “no excuses” approach, with a culture of high expectations — no matter what students were experiencing outside of school — coupled with strict discipline policies and rote classroom instruction. In turning around schools with histories of violence, he said, that approach rapidly eased safety concerns. “In situations where schools are sadly, seriously unsafe, a focus on structure and consequences addressed that problem very quickly and got us to safe environments very quickly,” he said.

But a few years ago, he had a change of heart.

Many Mastery schools are located in areas often plagued by violence. Students have seen family members, friends, and neighbors gunned down. For example, just weeks before school began this year at Wister, two neighborhood children became victims of gun violence.

“Before my school year started, I had two 6-year-old kids, one boy and one girl, didn’t know each other, literally within two blocks of this school” who were shot, said Jovan Weaver, Wister’s new principal. “So imagine the situation where this kid is now coming back to school and I’m like, ‘No, you’ve got to go back [home] because you don’t have black sneakers on.’ Like, what? No, we’re not going to hold that bar. That bar is not meaningful at all.”

So, two years ago, Mastery began a transition toward an approach that focused on social and emotional learning and intrinsic motivation — an emphasis on engagement in class as a source of personal reward for students. Each school got its own social worker, and strategies to address students’ emotional needs became a major emphasis in teacher training.

“Part of the job of a school is to mature young people and help them through the journey of childhood and young adulthood, and part of that is attending not just to academics,” Gordon said.

A new discipline policy focused less on minor infractions, and school leaders turned to restorative practices based on conflict resolution. The curriculum changed as well, with teachers presenting conceptual math instead of rote instruction and emphasizing critical thinking.

For Weaver, the shift resolved an internal conflict as a black male educator: The wealthy, predominantly white school where his wife teaches doesn’t have such a rigid structure. “There were certain messages that were sent in that particular environment, that our kids, our black and brown kids, cannot learn unless they are sitting up straight in a chair with their hands folded,” he said. “As a leader, it was something that I did not embrace at all because kids are kids. What skills are we actually focused on building?”

As a result of the change, students, parents, and teachers reported being happier with their schools on internal surveys. Suspension rates fell.

But then came the new state exams. While the city district’s overall third-grade math proficiency fell from 44 percent proficient to 18 percent, at Mastery’s Mann campus, for example, proficiency rates plunged from 77 percent to 25 percent.

Samantha Radinsky, a teacher at John Wister Elementary School, gives her second-grade class a math lesson. The school was taken over this school year by Mastery Charter Schools.

Finding a balance

For Gordon, the drop in math scores was a reality check. He was proud of the progress Mastery had made on addressing student climate, but the decline in academic performance, even given brand-new exams, was extremely distressing. And although Mastery’s math scores have rebounded somewhat, the challenge for Gordon now is to preserve the environment that allowed suspensions to drop 27 percent while reinstating practices that bolster student learning.

So this year, the network began reintroducing teaching techniques that had been a staple at Mastery schools for years, while seeking a middle ground between no excuses and restorative practices. It’s a “journey of trying to find out what’s the right mix,” Gordon said.

Specifically, the network is reintroducing procedural math instruction, which focuses on rote instruction like memorization and repetition.

But as Mastery works to rebuild the test score gains it saw in years past, another external factor could hinder its future. In October, Hite announced that the district would not convert additional district schools to charters under the Renaissance program in the 2017–18 school year, pending results of an evaluation. That evaluation, he said, will focus on a range of factors, including district finances and the performance of Renaissance schools.

Though Mastery runs nearly half the Renaissance schools in the city, Gordon said he isn’t worried about the evaluation. He’s confident that the program will return, in some form or other, as “tens of thousands of students are suffering in low-performing schools” across Philadelphia. And when it does, addressing school climate will be an essential part of the conversation.

As Shorr put it, “Sometimes you can have a school where they’ve got the culture part down but they haven’t gotten to the academic performance piece yet, but I have never seen a school where the academic performance piece is in place and the school culture is bad.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)