As First Lady, Jill Biden to ‘Bring a Lot More Power’ to Helping Students in Military Families

Educators might be excited to have one of their own in the White House next month, but there’s another constituency that future first lady Jill Biden is planning to highlight as part of her work in the administration.

“You are going to have a military family back in the White House,” she told families of veterans and active duty service members in a November virtual address. At the recent Military Child Education Coalition’s summit, she announced her intention to relaunch Joining Forces, an initiative she co-led with Michelle Obama during her previous time in Washington.

That effort focused on the challenges confronting the roughly 2 million children of U.S. military and veteran families. About 1.2 million have a parent on active duty and the majority are in regular districts, not Department of Defense schools. They transfer, on average, six to nine times during their K-12 years and frequently adjust to inconsistent state academic standards and graduation requirements.

“They face long separations from parents, multiple moves, and increased stress and anxiety,” Biden, the grandmother of two military children, told the coalition. President-elect Joe Biden’s son, Beau, who died of cancer in 2015, served in the Army National Guard during the war in Iraq. Jill Biden has frequently cited the example of a teacher who supported her granddaughter Natalie during her father’s deployment by hanging a photo of his unit in the classroom. “It made her feel special,” she told the coalition. “It showed her how special his service was.”

In 2016, Jill Biden spoke to members of the American Educational Research Association, urging them to include military children in their work. And she hosted a White House conference on Operation Educate the Educators, a project devoted to integrating knowledge about military-connected children into teacher preparation programs.

“She’s going to have a lot more power now,” said Ron A. Astor, a professor at the University of California Los Angeles who participated in those events and led research projects involving school districts serving high numbers of military-connected students. “I think military families have been off the radar since she’s left.”

Announcements of incoming White House senior staff members reinforce the notion that the future first lady plans to focus on military children and families. Mala Adiga, who previously worked as director for higher education and military families at the Biden Foundation, will serve as Jill Biden’s policy director.

‘It is an identity’

President Trump’s relationship with the military community has been mixed. He has frequently clashed with top Pentagon officials, but said he has the support of service members. Last year, he diverted funds intended for the construction of schools on military bases to help build a border wall. And his past disparaging comments about service members drew fire from veterans and elected officials in the weeks before the election.

Joining Forces took root during the Obama administration amid growing awareness of the strain the extended war in the Middle East put on military children. One study linked deployment of a parent to higher rates of depression, anxiety, and aggression.

Another study, which Astor led at the University of Southern California, found more substance use and weapon carrying among military students than among their nonmilitary peers, and that children with a parent on active duty were more likely to be bullied than their peers.

The USC project, with funding from the Department of Defense Education Activity, trained future school social workers for positions in eight San Diego-area districts. Schools also added Veterans Day ceremonies and other events to recognize the military community.

The Chula Vista Elementary School District, where more than 10 percent of students have family members in the military, has eight “military and family life counselors” who help students through transitions and provide training for teachers on aspects of military life.

New survey data shows the rates of substance use, depression and bullying have declined in those districts, Astor said. He attributed the improvements to new personnel who understand the stressors military students face.

“The reductions are dramatic,” he said of the data, which has yet to be released. He added that positive results, such as students feeling connected to peers and adults at school, are increasing.

Students who attend on-base schools and then change to district schools can experience culture shock, explained Joanna Dasher, who grew up as an Army “brat,” moving six times by sixth grade. She switched to a regular district in middle school and thinks it’s important for educators to recognize experiences like hers.

“I think Army brats, military brats are resilient,” Dasher said, adding that being a “culturally responsive teacher” includes being sensitive to what it’s like to grow up as a military child. “It is an identity.”

Now married to an officer in the Georgia Army National Guard, and with a daughter in kindergarten, the family is only together three weekends a month. They live in Atlanta, but Maj. Russell Dasher works in Savannah. Unlike families with an active duty service member, those with a parent in the National Guard aren’t always transferred when there’s a new assignment.

Teachers who understand the differences between branches can help students feel more accepted in the classroom, added Dasher, an Army veteran and former English teacher who now works in educational technology. “A Navy brat’s experiences during this war on terror have been demonstrably different than an Army brat or a Marine brat,” who might have had a parent deployed multiple times since 2001, she said.

Researchers, and advocates pushed for better data collection to ensure that schools know whether they have military children in their classrooms. The federal Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 requires states to report achievement and other data for students who have a parent on active duty.

According to the most recent Show Me the Data report from the Data Quality Campaign, 32 states now meet that requirement, up from 19 last year.

Talking to ‘every American’

Becky Porter, president of the Military Child Education Coalition, said she’s optimistic that Jill Biden’s role as first lady will spark a renewed focus on the academic and social-emotional challenges facing military children.

“Her position … will provide her a platform to talk to every American,” she said.

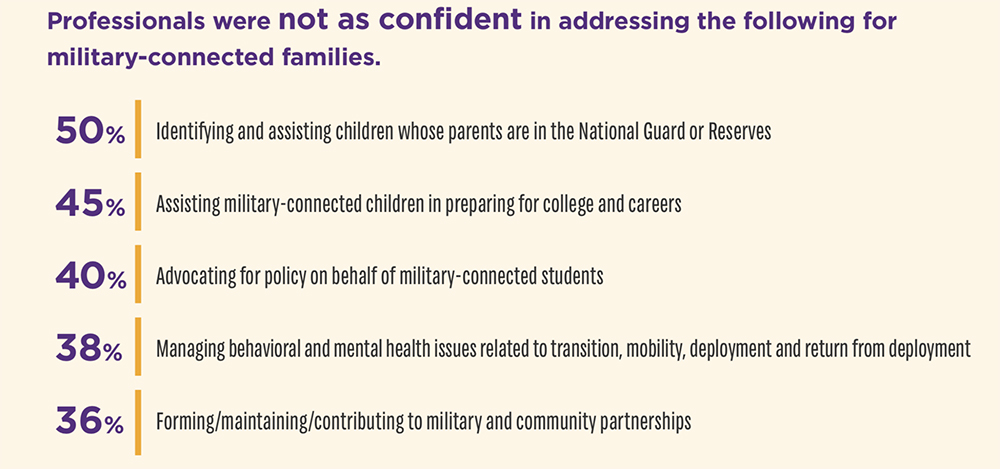

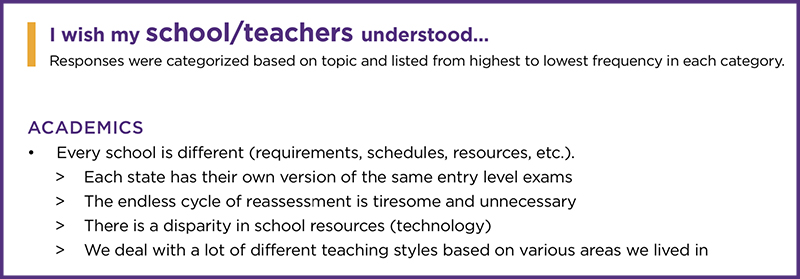

The organization’s new survey results show students are often frustrated by having to retake assessments and courses every time they move and that educators don’t have a strong understanding of the military lifestyle.

Another survey, conducted by the Institute for Veterans and Military Families, shows that resources related to K-12 schools were among the top needs of active duty service members during the pandemic.

On top of the Every Student Succeeds Act, there is a growing voluntary effort at the state level to identify Purple Star Schools that cater to students with a parent on active duty, in the National Guard, or reserves.

Rachel Bell, the wife of an Army veteran in San Antonio, said such a designation could be especially helpful in her area so “parents who are on their way here can make educated decisions about what’s best for their family.”

While it calls itself “Military City, USA,” the San Antonio metropolitan area has 17 school districts, and families that have been transferred might not know how to “navigate the local dynamics,” she said. One issue important to military families, for example, is whether schools allow excused absences for a student whose deployed parent is home on leave.

In addition to voicing support for military children, some advocates are hoping the new administration will support funding increases for Impact Aid. The program makes up for the loss of property taxes for public schools on military installations and other federally owned land. The Trump administration’s fiscal 2021 budget recommends a decrease, saying that after roughly 40 years of the payments, schools should have adjusted to the lack of tax revenue. Both the House and Senate funding bills include an increase.

“The vast majority of military-connected students attend our nation’s public schools,” said Hilary Goldmann, executive director of the National Association of Federally Impacted Schools, which represents more than 1,200 districts. “Impact Aid is a critical funding source for the school districts that educate them.”

Disclosure: Linda Jacobson co-wrote a collection of books with Ron A. Astor on schools that serve military children.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)