As Early Ed Teachers Prepare for Fall, New Study Backs Efforts to Support Young Children’s Mental Health

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

Zakiya Sankara-Jabar was taking nursing classes at Wright State College in Dayton, Ohio, when she started getting phone calls from her young son’s teacher at the on-campus child care center.

Amir was having a tantrum; he threw a toy or was “refusing to transition,” the teacher told her. Sankara-Jabar repeatedly had to leave class to get her son, and ended up having to withdraw from school that semester. The center’s staff suggested maybe Amir, the only Black boy in his class at the time, needed therapy and offered to call in psychology majors to observe him. They eventually asked her not to bring him back.

“It just continued to escalate,” Sankara-Jabar said. She told the teachers, “You guys seem like you don’t expect this. He’s 3.”

Amir’s preschool days are far behind him, but now Ohio has a program that helps preschool teachers solve behavior challenges before they reach the point of removing children from the classroom. New research from Yale University supports the model, showing that specialized training and support for teachers improves preschoolers’ behavior and reduces the risk of suspension and expulsion. In addition, the study found that the intervention has the same positive benefits on other children in the classroom. The findings are timely as schools prepare for the transition to pre-K and kindergarten this fall for millions of young children who underwent a critical stage of their development during the pandemic. Many have missed out on classroom experiences, and Black and Hispanic families with young children have faced particular hardship and loss.

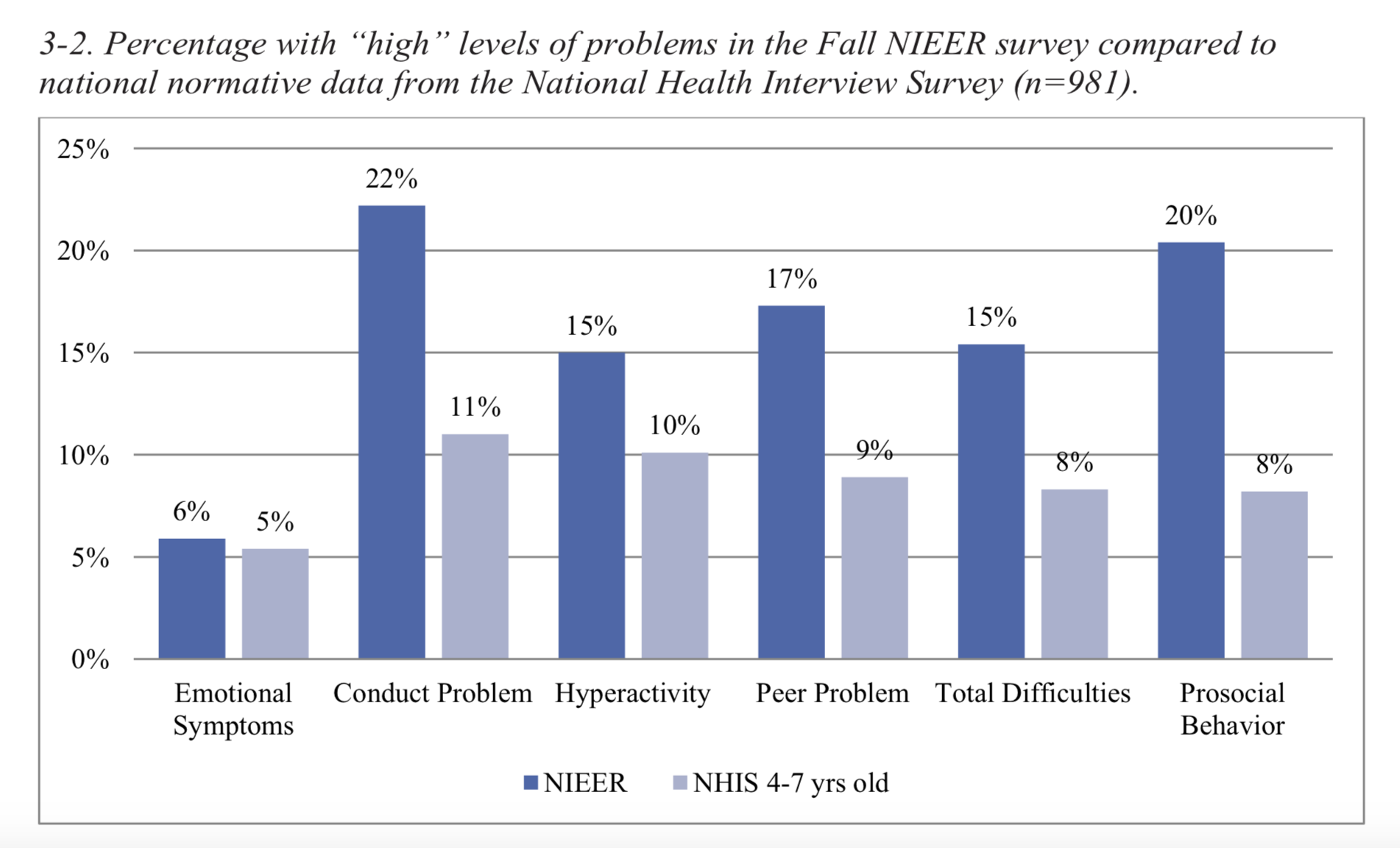

Even in a typical year, young children entering school can have a hard time separating from parents and adapting to teacher’s expectations. But recent data shows parents reporting their children are experiencing more hyperactivity and other behavior problems compared with levels found in a nationally representative, pre-pandemic survey.

“With disruptions resulting from the pandemic, I worry that schools want to play ‘catch up’ rather quickly and … undermine [children’s] social and emotional learning and mental health,” said Chin Reyes, a developmental scientist at Yale and co-author of the study “All children experienced stress and disruptions — some significantly more than others. And not just the children, but also the teachers.”

Published in the journal Development and Psychopathology, the research focused on Ohio’s Whole Child Matters program, in which early-childhood mental health consultants make at least six visits to preschool classrooms to help educators develop positive relationships with children. Fifty-one classrooms were randomly assigned to participate in either the program or a control group.

The results showed that teachers who work with consultants feel a greater sense of control over challenging situations with children, a key finding since “expulsion is largely a teacher decision,” wrote Reyes and co-author Walter Gilliam, a professor of child psychiatry and psychology at Yale.

The “target children” — those who were getting in trouble — showed improvements in social-emotional skills, such as greater independence and ability to self-calm. The same improvements were seen in the children’s peers, adding to Gilliams’s 2007 findings on a similar program in Connecticut.

Racial disparities

The Ohio study builds on Gilliam’s 2005 research, which found expulsion rates among preschoolers exceeded those of K-12 students, especially for boys and children of color.

Federal data confirmed those trends in 2014, showing Black children made up 18 percent of preschool enrollment but accounted for almost half of those suspended at least once — a cycle that data shows leads to later discipline problems and contributes to what has been described as the “preschool-to-prison pipeline.”

Tunette Powell, a Black mother of three, knew that experience all too well. Also in 2014, an Omaha, Nebraska, child care center repeatedly sent two of her boys home for acts such as throwing a toy and pushing over a chair, when no one was hurt.

Once Powell’s boys entered public school, they were never suspended again. “I put in a lot of work to try to strip that from who they were,” she said. “You don’t want that to become their narrative.”

Gilliam’s work prompted nationwide efforts to prevent expulsions in early learning programs. Twenty-six states now have programs like Ohio’s or have passed legislation limiting the practice, he said. But telling teachers they can’t remove a child without giving them tools to address problem behavior can lead programs to become more selective about which children to enroll in the first place, he said.

“State regulations ban hard expulsions, but not necessarily soft expulsions,” added Reyes. Teachers might frequently ask a parent to pick up a child early or say the child isn’t the “right fit” for the program.

Iris Williams, a Black mother of two in San Antonio, Texas, called it a “workaround.” Her state passed legislation in 2017 banning most out-of-school suspensions in pre-K through 2nd grade. But that didn’t stop Williams from receiving calls at work when her daughter Heaven Ellison, who has ADHD, had problems at school.

“I hate to say they just didn’t want to deal with her, but that’s what I feel like,” Williams said about her daughter’s teachers. “She never got suspended. They would send her home and say, ‘We’re sending her to a safe place.’”

In addition to state laws requiring teachers to seek alternatives to removing children from the classroom, the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services either restrict or discourage suspension and expulsion of young children and recommend programs in which teachers have access to mental health professionals. The recent federal relief package includes $24 billion in child care funding that states can draw on to support children’s mental health.

‘Not a fix-it approach’

In California, Donmonique Daniels has been a teaching assistant at a preschool in Oakland for three years. Recently, a 5-year-old boy in the class, who is about to be adopted, became aggressive toward other children. If a child took a toy away from him, he would retaliate by hitting.

But Daniels works for Kidango, a network of San Francisco Bay Area preschools that in 2018 launched a program in which mental health professionals meet weekly with teachers to discuss common behavior issues. Talking with a consultant and the boy’s adoptive father, the teachers learned that the child “has some separation anxiety due to being swapped around.” And he would become especially agitated if teachers told him he was having a hard day.

Consultation, Daniels said, gives teachers “perspective on how to tap into the way kids need us emotionally.”

The consultants don’t wait until a child is considered a problem to get involved, said Tena Sloan, a vice president with Kidango.

“We are available with support in challenging times and in times that are working,” she said. “That’s why it’s not a fix-it approach.”

At the center where Daniels works, she said teachers are already mentally preparing for the fall, and thinking of how to make the space “as familiar as possible” for new children enrolling. They’ll label chairs and put photos of the children on their “cubbies.”

“The pandemic has definitely changed a lot for the kids,” she said, “and for us.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)