As Districts Scramble to Keep Up With Omicron Surge, White House Bolsters Schools’ Testing Supply

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Highline Public Schools, near Seattle, placed an order in December with the Washington Department of Public Health for rapid COVID-19 tests. The shipment still hasn’t come in.

That leaves Superintendent Susan Enfield balancing keeping athletic programs running — which requires students to test three times a week — against maintaining an adequate supply of kits for the test-to-stay program and students displaying symptoms.

“We have a few thousand [tests] right now,” she said. “At the rate we’re going through them, that’s not going to last us more than a couple weeks.”

On Wednesday, the Biden administration took steps to address the demand, announcing it will send 5 million rapid and 5 million lab-based PCR tests to schools each month to support screening and test-to-stay programs, which allow students to remain in class after exposure.

During a surge, the Department of Health and Human Services and the Federal Emergency Management Agency will organize testing sites in or near schools for students, staff and families. The new resources are in addition to the $10 billion for school-based testing released last year.

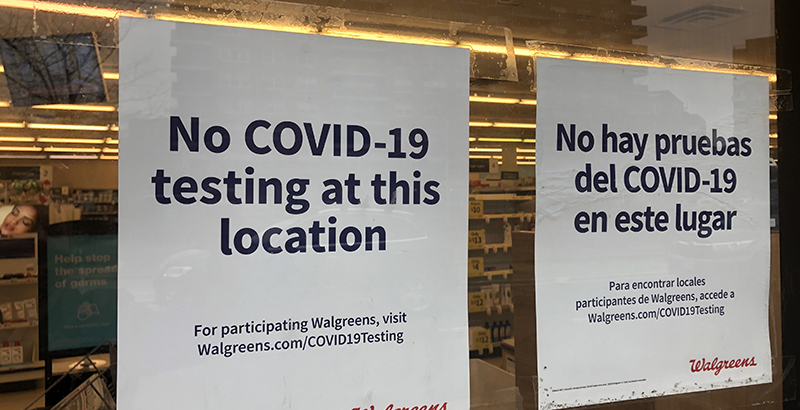

In Highline, and in districts across the country, the testing supply has been sagging under the weight of Omicron and increased testing protocols. Requirements that students test after the holidays, combined with test-to-stay procedures, have created fierce competition for kits at the same time similar mandates are being enacted in other parts of society. Long lines at testing facilities, sold-out stores and overdue PCR results are contributing to accusations that President Joe Biden hasn’t managed the need for testing as well as he handled the vaccine rollout.

Republicans, but also some Democrats, criticized the administration’s response to the Omicron outbreak at a Senate committee meeting Tuesday, accusing top health officials of acting too late to make more tests available.

“I’m frustrated we are still behind on issues as important to families as testing, and supporting schools,” Senate education Chair Patty Murray said during the hearing.

Biden is expected to discuss his “whole-of-government” response to the surge Thursday. According to the White House, the administration has been finalizing contracts with companies to distribute at-home tests through the Postal Service and completing work on a government website where people can order them. Starting Saturday, insurance companies will be required to cover the cost of at-home tests, the Department of Health and Human Services announced Monday.

But while distributing tests to everyone who wants one might be “admirable,” districts need a more targeted approach, said Julia Rafal-Baer, who recently left Chiefs for Change to launch ILO Group (for “in the life of”), where she consults with districts on pandemic recovery efforts.

Districts, she said, “need to count on a consistent supply of tests with a real focus now on those who are mildly symptomatic,” she said.

Even as they scramble to have enough tests on hand, educators are thinking ahead to a time when testing asymptomatic students won’t be necessary. Districts, Rafal-Baer said, need to begin looking at “shifting protocols” in order to keep schools open as more students get vaccinated.

“Any kind of shutdown at this point is going backwards,” she said, “and it’s going backwards to a point that we know is devastating.”

For now, COVID testing is part of keeping schools open.

Mara Aspinall, an adviser to the Rockefeller Foundation and a biomedical diagnostics expert at Arizona State University, said that in 2020, commitments from the foundation and governors to purchase tests allowed manufacturers to accelerate production.

Through the State and Territory Alliance for Testing, rapid tests went directly to schools and nursing homes. The federal government’s bulk purchase of BINAXNow tests also ensured states and districts a dependable inventory.

But before the Delta variant, when cases were declining, demand for testing tapered off. Such fluctuations, Aspinall said, make it hard for “manufacturers to anticipate whether their product will be sold when it’s available, or whether it will sit in a warehouse and expire.”

Abbott Laboratories, which makes BINAXNow, shut down a lab in June and then restarted production when the Delta variant drove up demand.

‘Can’t justify going remote’

Whether schools can back off testing and tracing asymptomatic students, however, is still a matter of considerable debate, especially at a time when positive cases are reaching all-time highs.

Florida officials last week said they would begin targeting testing to those who are at higher risk for getting severely sick from COVID-19, which contradicts guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One infectious disease expert described the switch as a “recipe for disaster.”

In the Cobb County Schools in Georgia, leaders said they would increase access to testing but no longer require contact tracing, in keeping with new state guidelines. Superintendent Chris Ragsdale said contact tracing — tracking down all possible close contacts of a student who tests positive — has drained staff resources.

The district’s COVID tracker was last updated Dec. 17, before the holiday break, but according to the county health department, community transmission is currently high, with 2,657 cases per 100,000 residents.

“Giving up on contact tracing feels one step closer to giving up entirely on any pretense of mitigation,” said Cobb parent Alan Seelinger, among those who have advocated for masks and remote learning during COVID surges. “Our continued pleas for the superintendent and school board majority to make our schools safer feel pointless.”

But to Ragsdale’s point, tracing takes up staff time when schools are already coping with shortages. Washington superintendent Enfield, a former high school English teacher who is one of two finalists for superintendent in San Diego, taught a sixth grade science class Monday. She’s also sent all central office staff members with teaching certificates to cover classrooms.

With student absentee rates about 20 percent, Enfield said some teachers have pushed for remote learning, but as long as 80 percent of kids are coming to school, “I can’t justify going remote right now,” she said.

In addition, some schools are severely short-staffed because teachers are sick. “If you have a critical mass of staff at school out, you’re not talking about remote learning, you’re talking about no learning,” she said.

Considering COVID risk

If districts see declining support for testing students without symptoms and not enough staff members to trace close contacts, they should make decisions based on the level of COVID risk in a school community, said Leah Perkinson, a manager at the Rockefeller Foundation.

Immunocompromised students, those in multigenerational households with essential workers and those in contact with many people on a daily basis should be prioritized for screening, she said.

“The risk that they come into the school with COVID is higher, the risk of them spreading to others is higher and the consequences of infection are more dire than they are for their non-immunocompromised peers,” she said.

Calls for updated guidance regarding COVID testing are also coming from health care providers.

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and its PolicyLab last week released new recommendations for K-12 schools that suggest possible testing for those with mild symptoms and discontinuing weekly testing for students and staff unless transmission is high — and even then, just on a voluntary basis.

“Our guidance goes further than that of CDC’s in allowing more exposed but asymptomatic children and staff to return to school and reducing staff burden for contact tracing and weekly testing of asymptomatic individuals,” according to the document.

Elizabeth Lolli, superintendent of Dayton, Ohio, schools, decided to partner with her county’s health department for testing to avoid overwhelming staff and drawing criticism from families over COVID protocols.

“There’s enough controversy to keep everybody away from the reason that we’re here — so we can focus on kids,” she said.

But the district still requires students to get tested if they’ve been out sick, and drive-through lines at the testing site at the Montgomery County fairgrounds stretch around the track, with waits up to an hour.

Before the most recent outbreak, some education leaders were also hearing administrators ask: “What’s the end game for this?”

“At some point, that’s a fair question,” said Jason Leahy, executive director of the Illinois Principals Association. He added that some schools are sending students home because they don’t have rapid tests on hand. But then students are absent while waiting for results of PCR tests.

“COVID is not going away. We have to figure out how to live with it,” he said. “We need the CDC to step up and give an idea of what that would be.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)