As Distance Learning Pushes Parents Into Pods, Some Look for Ways to Make the Model More Inclusive

Tyneisha Gibbs and a few friends in East Orange, New Jersey, were in the midst of organizing a child care co-op called Umi-verse when the coronavirus hit the U.S.

But this summer, when it became clear that families were facing the prospect of another three months or more of school closures, they saw an opportunity. They flipped their side project into a service matching professional educators with parents tired of balancing work and their children’s distance learning schedules.

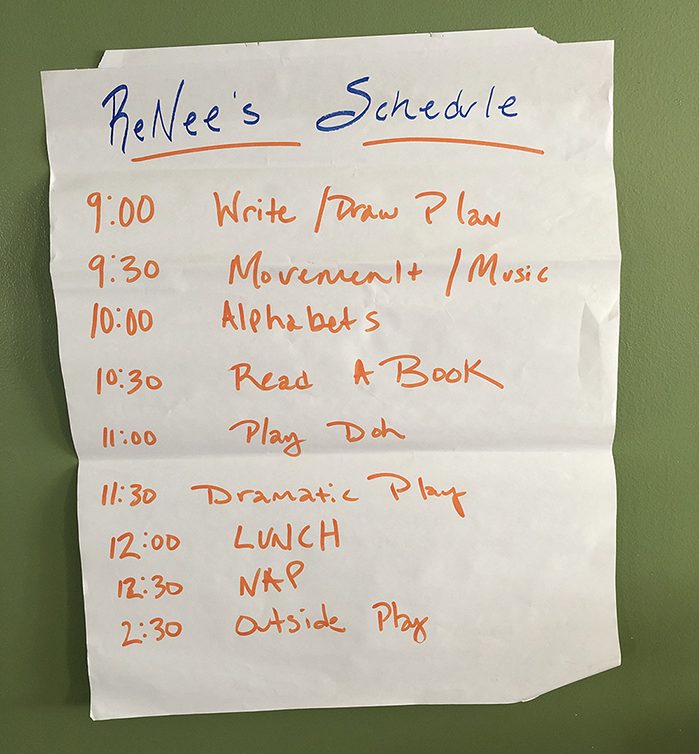

“It’s kind of self-serving, because we need it, too,” said Gibbs, whose 3-year-old daughter Re’Neé is in the East Orange School District’s pre-K program.

Gibbs calls it “the village.” So far, Umi-verse has received interest from more than 30 parents and nine educators. Costs range from $150 to $350 a week, but she is also exploring opportunities for “pod coordinators” to become licensed child care providers so they can serve families that qualify for subsidies.

‘Cascading questions’

In many ways, the phenomenon is nothing new. What Gibbs calls a village, some describe as pandemic versions of homeschool co-ops. Others associate them with the pre-COVID concept of microschools. But what’s new about “pods” is the context: Until the coronavirus gets under control, the intention is to limit the circle of children and adults who interact with one another while providing what shuttered schools can’t.

The push for pods is being fueled largely by anxiety rather than ideology. Parents who never would have looked twice at homeschooling are turning to pods out of exhaustion from the five-month COVID regimen of juggling work and at-home care. They fear sending children back to school while the pandemic still rages. But pods’ potential costs are raising new questions about whether the practice will exacerbate the gap between rich and poor at a time when the virus has disproportionately hit low-income families. That prospect has already pushed a host of nonprofit organizations and individual pods to help subsidize costs.

Multiple roads lead families to pods. “It’s not just an option for parents to handle day care stuff,” said V. Darleen Opfer, the vice president and director of education and labor at the RAND Corp. “For the people I’ve spoken to that are doing it, it’s as much about academic learning loss.”

Pod families generally fall into two categories — those withdrawing from their school districts completely and those who are using pods merely to supplement state and district remote learning programs.

Jessica Erensoy, a mom of three in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, is in the first group. Between November and January, her daughter Charlotte “was bringing home every sickness under the sun” from her elementary school. Erensoy caught pneumonia twice, missed five weeks of work and ended up leaving her job.

So the thought of sending Charlotte, 6, and her almost 5-year-old twin brothers into classrooms this fall was leaving Erensoy feeling anxious and overwhelmed. Plus, she didn’t think Charlotte would adjust well to a classroom full of mask-wearers and plexiglass partitions.

“I just thought maybe I can do this better and more appropriately,” said Erensoy, who has a background in early-childhood education. Now she’s looking for another family with similar-age children, preferably someone who can take the lead in math.

Prior to the pandemic, she had dismissed homeschooling as “something that cost a fortune.” But after joining a few Facebook groups and learning how families found learning materials and shared expertise, she feels more confident in her decision. “Just to see how different people are making this work takes some of that edge off.”

Erensoy is among scores of parents whom Michael Donnelly, senior counsel at the Home School Legal Defense Association, expects to choose that model this fall — even though, he said, “they may not think what they’re doing is homeschooling.” Family co-ops, shared teaching duties and even hiring private tutors have traditionally been part of that framework.

Donnelly predicts the number of homeschooling families to at least double this fall, fueled at least in part by the coronavirus and the embrace of pods. And some estimates, he said, show that the figure could increase from the current 2.5 million to at least 8 million.

But many pod families have no intention of leaving public schools. Gibbs in New Jersey — and her Umi-verse moms — are among them. Many of them work in public education. Gibbs, for example, works with the Statewide Network for New Jersey’s Afterschool Communities. Another mom is a counselor at a charter school, and a third works in early-childhood education. But they still need someone to make the at-home school day run smoother so they can get their own work done.

“You’re feeling bad. You’re feeling guilty,” she said. At first, she said, she had a schedule for Re’Neé, but that “went out the window.”

For some, partnering with pod families is about rebuilding peer groups.

“It’s important for them to have interaction with other kids outside of a Zoom call,” said Christina Giovannelli-Caputo, a mother of four in suburban Chicago.

She’s joined a nature-oriented homeschool group in her neighborhood as a way to “cut the cord of technology” and give her children a chance to dig in the dirt and socialize. Membership was free, but the groups offer “bundles” of resources, such as books, downloadable materials and online discussion groups, for a flat $29 or a monthly $19 subscription.

Whatever has motivated families to join them, pods have come under fire for potentially exacerbating opportunity gaps between middle-class families who are used to pouring their resources into supplemental activities for their children and those who are struggling financially.

Elysa Severinghaus, executive director of EdNavigator in Boston — a nonprofit that works with companies and community-based organizations to help families choose schools and afterschool programs — said the concept could favor families with more flexible work arrangements.

“Even if we coordinate with other families, then what happens when so-and-so has to take an extra shift?” she asked.

For many single parents and hourly employees, she said, pods lead to “cascading questions,” including whether the pod-hosting parent feeds children during school hours, attempts to pick up grab-and-go meals, or has transportation to take them to a park or other activity.

‘The potential of the pods’

Jason Weeby, the director of strategic initiatives at the NewSchools Venture Fund, a nonprofit that funds new models of learning, is skeptical about the extent of the pod-related equity issue. He calls headlines about pod families spending six figures to hire a teacher and renting out pod apartments extreme examples.

“This narrative that pods belong to the wealthy is bothersome to me and takes away from the potential of the pods to be a solution for anybody,” he said.

Part of the problem may be that the pod model is so fresh that public policy hasn’t caught up with it yet. Some organizations, including those that favor free market education models, are stepping into the breach.

The National Parents Union is one of four groups receiving a total of $1 million from the Vela Education Fund, launched with funding from the Walton Family Foundation and the Charles Koch Institute. The union is offering grants of $20,000 to $25,000 to member groups in eight states that want to help low-income Black and Latino families develop homeschool pods.

“We have the national polling that shows that families across America — and across demographics — are serious about this, and they will not jeopardize the health and safety of their children,” said Keri Rodrigues, president of the organization. She called pods “a trendy new term for something that we have been doing for generations.”

Her own children will be part of a “microschool” of six children, including four with special needs. “We’ve pooled our resources and hired a special education paraprofessional to help,” she said.

Like Gibbs’s Umi-verse in New Jersey, several pod organizers are making extra efforts to attract lower-income families. Darleana McHenry, who ran afterschool programs in schools outside of Los Angeles before the closures, recently finished the requirements to use her home as a family child care center. She has 1,000 square feet where she plans to provide care and education for 3-to-7-year-olds, combining lessons in organic gardening with academic skills. She also plans to offer an online program focusing on math.

She has yet to decide whether she’ll offer her own curriculum or supplement a district program. But she plans to be prepared for both. “Right now, my thought is to target Black families,” including those on the front lines, she said. “Someone has to address the needs of essential workers.”

Families in control

For families taking the homeschooling route toward a pod, President Donald Trump and Senate Republicans want to help. The proposed School Choice Now Act puts into formal terms the president’s position that parents should be able to choose another option if they’re unhappy with their local district’s reopening or distance learning plans.

The bill would provide emergency funding for state-level organizations that provide scholarships for students to attend private schools — including homeschooling expenses. At least 15 states currently have such organizations, funded through tax credits for donations. But so far, only New Hampshire includes homeschoolers.

Weeby also stressed that “there is plenty of room for public institutions to step in” and help families create pods or implement other solutions to address both academic and child care needs.

He highlighted the city of San Francisco’s plan to open “learning hubs” in libraries, museums and other community sites for children in low-income families this fall. In Florida’s Broward County Public Schools, instruction will be remote, but the district will offer morning and afternoon small group sessions for students in elementary grades. And Tulsa Public Schools in Oklahoma is working with community-based organizations to open up their facilities for children on distance learning days.

Debbie Medley, the director of expanded learning for the district, said she hopes to secure “spaces in areas where there are not a lot of options for families” who can’t pitch in for a private pod teacher but don’t qualify for child care vouchers. The district is also working with the business community on continuing to allow flexibility in work schedules for families this fall.

“Community organizations can only do so much,” she said.

Disclosure: The Walton Family Foundation provides financial support to the Vela Education Fund, the National Parents Union and The 74. The City Fund provides financial support to the National Parents Union and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)