Arts Education Program Increases School Engagement, Study Finds

As states like California spend billions to increase arts offerings, research shows the academic and social-emotional value of cultural education

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

K–12 arts education — viewed as a necessity by many parents, but often crowded out of school budgets and instructional time — can boost students’ writing skills and build empathy, according to a study published late last year. Kids participating in a citywide arts program in Houston also saw improved behavior and increased college aspirations, the authors found.

First circulated as a working paper before the pandemic, the article was accepted for publication in November at the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. Its conclusions are difficult to ignore after both schools and the arts world were rocked by COVID-19, with an estimated hit to the creative economy totalling millions of jobs and tens of billions of dollars lost in 2020 alone. Arts education in some states had to be sustained through the infusion of emergency funds from Washington.

The study will also inform public policy decisions as school systems look to get back on their feet. Just a week before its publication, voters in California approved a ballot initiative that will provide nearly $1 billion annually to increase access to arts and music programs in schools. The sizable new appropriation, which isn’t funded by new taxes, passed by a wide margin amid advocacy by celebrities like Dr. Dre and Katy Perry.

Brian Kisida, a professor at the University of Missouri’s Truman School of Public Affairs and one of the paper’s co-authors, said that its results showed that the arts are a kind of “secret sauce” in keeping young students interested and involved in school. Particularly as schools try to lead a revival after years of lost, delayed, or incomplete learning, he added, arts instruction shouldn’t be cast aside in favor of core subjects like math and English.

“The key question is, how do you keep students engaged in their own learning in such a way that they are intrinsically motivated to want to go to school — and when you present them with the idea of going to college, it doesn’t sound awful?” said Kisida, who acted as a technical consultant to backers of California’s Proposition 28 campaign.

The study examined the impact of participation in Houston’s Arts Access Initiative, a coalition of more than 50 cultural institutions, philanthropies, and other local organizations dedicated to providing more arts resources in schools that previously lacked them. One of the initiative’s earliest priorities was conducting a comprehensive audit of the Houston Independent School District — one of the largest in the country — that revealed that roughly 30 percent of the city’s 209 elementary and middle schools offered neither a full-time arts specialist nor any arts programming outside of school hours.

Given the widespread gaps in availability, it came as no surprise that demand for the program outstripped its initial resources, with 60 schools applying to fill just 21 slots for the initiative’s initial rollout. Kisida and co-author Daniel Bowen, a professor of educational administration at Texas A&M, worked with the district to follow two groups of schools randomly selected to either participate in the initiative or act as a control group. In all, just over 10,000 children from grades 3–8 participated.

Among those that took part, results were strong. Compared with the control group, they experienced about five additional “school-community partnerships” (a broad category encompassing everything from a half-day trip to the Houston Ballet or the Museum of Fine Arts to a semester-long collaboration with a full-time artist) each year. The learning opportunities represented a hugely varied sample of workshops, residencies, and excursions: 54 percent related to theater, 12 percent to dance, 18 percent to music, and 16 percent to visual arts.

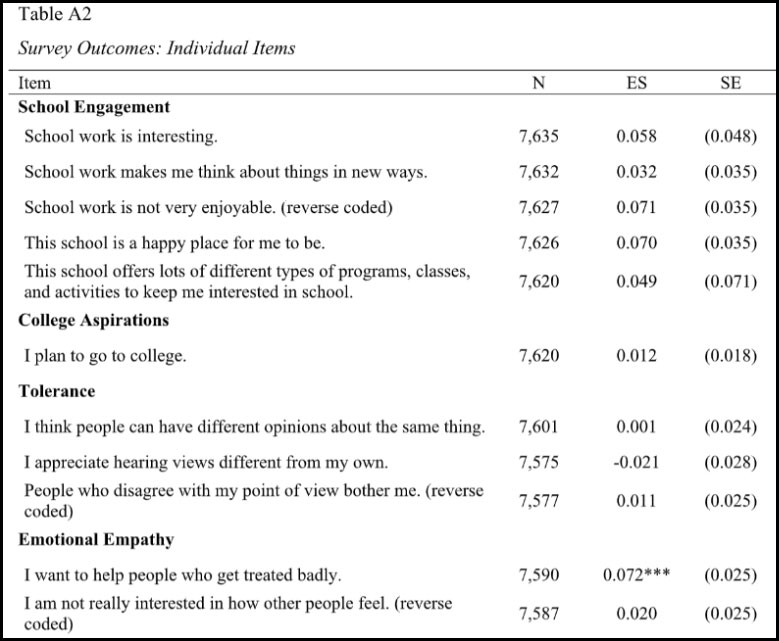

Those experiences generated significant academic and social-emotional rewards. Participants earned significantly higher scores in writing on Texas’s standardized test, with particular gains in expository writing. They were also 3.6 percentage points less likely to be involved in a behavioral infraction. In accompanying surveys, elementary students also showed higher levels of emotional empathy (as measured by agreement with statements such as, “I want to help people who get treated badly”) and demonstrated more engagement in school and interest in potentially attending college.

Those effects are broadly similar to those detected in other research on the effects of arts education, much of which has focused on field trips to cultural institutions like museums and theaters. But Bowen said the Houston study offered particular value in emphasizing experiences that predominantly occur within school buildings, the way most K–12 students tend to encounter the arts.

“Virtually all of these experiences were happening during the regular school day and in their regular school environments,” Bowen said. “We’re hoping this will provide research that tells us more about the impact of the arts in more typical learning environments.”

The findings also contribute to public understanding of school-community partnerships, which are an increasingly common strategy to bring creative opportunities to schools where they have traditionally been in short supply. Over the past decade, such partnerships — which typically enlist a wide range of cultural partners to write grants and provide staff to school art programs — have sprung up in large districts like New Orleans, Los Angeles, Dallas, Chicago, and Seattle.

A similar study conducted by Kisida and Bowen on behalf of Boston’s EdVestors coalition found that participants in Boston Public Schools’ Arts Expansion Initiative were less likely to be absent from school and more engaged with their studies. Parents also reported higher levels of engagement with their children’s education.

Even for districts located far from major urban centers, resources abound for potential collaborations with local museums and dance troupes. According to the American Alliance for Museums, American museums devote roughly $2 billion each year to educational programming, with roughly three-quarters going to K–12 schools. That funding is like low-hanging fruit for schools and districts that have trouble financing their own arts offerings, Kisida said.

“It’s a policy development that is very rich and may be flying under the radar for a lot of education policy folks,” he argued. “What makes this such a unique opportunity for schools is that they are able to tap into the passion that already exists in these mission-driven nonprofits to supplement their services.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)