‘Are We Really Going to Fail Those Students?’ With State Tests Next Month, Tennessee Reconsiders Holding Back Third Graders

Michigan is close to repealing a similar law as the debate over the benefits and drawbacks of retention continue.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In 2020, Faith Miles saw her kindergarten year broken up by the pandemic. Already slower to pick up language skills than her older siblings, Faith was further set back by months of remote learning.

“In the midst of the pandemic — even without a learning disability — you can’t get a 6-year-old to sit in front of a laptop,” said Tamara Miles, Faith’s mother. “Her attention span is not that long.”

Now in third grade, Faith is among the nearly 3,900 students in the Metro Nashville Public Schools — and thousands more throughout Tennessee — who risk failing the state reading test this spring. That means they could be impacted by a 2021 law — taking effect this year — that requires proficiency to move onto the fourth grade.

Pressure has been building on state lawmakers to amend the law as testing season approaches next month. Parents, advocates and educators say it’s unfair to base the decision on one assessment, especially for students who were in kindergarten when the pandemic hit. But state officials and Republican legislators argue it’s wrong to promote students who aren’t ready.

“We’re living with this COVID two years for the next 12 years of our life, trying to get these kids caught up,” Rep. Scott Cepicky, chairman of the House Education Instruction Committee, said last week during a hearing on the issue. “We cannot keep doing this and condemning these kids to a life of possibly poverty, incarceration, drug abuse, alcoholism, teen pregnancy, gang violence.”

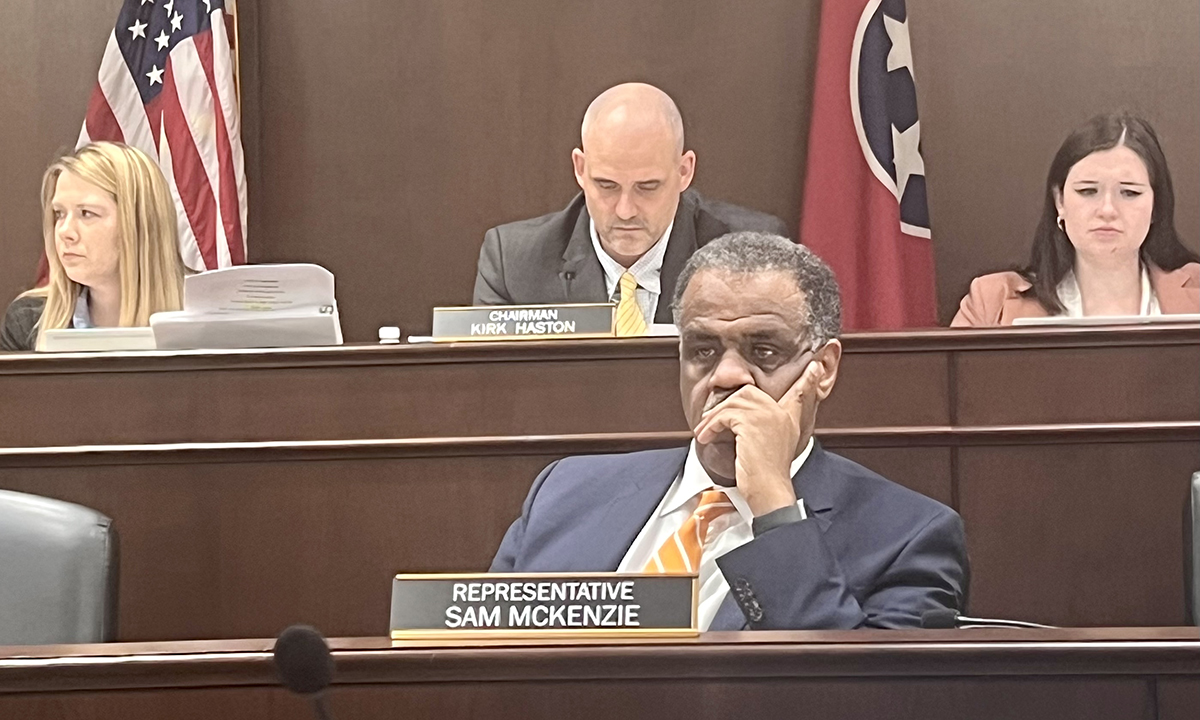

Legislators are currently considering Cepicky’s amendment to tweak the law to allow students who score in the “approaching expectations” range to advance to fourth grade if they score in the 50th percentile on a literacy “screener” test. The law already offers opportunities to retake the state test as well as summer school, tutoring and ultimately, an appeals process. But some district leaders are still opposed.

“Some of our parents will not take advantage of the resources that you’ve set in place,” Clint Satterfield, director of the Trousdale County Schools, told lawmakers during another hearing last month. “They will choose to take retention and that is sad. That’s an unintended consequence.”

Cepicky’s amendment would also require students who are retained in K-3 to receive tutoring. That the law didn’t already include such a provision, he said, was one of its “shortcomings.” The Senate Education Committee passed similar legislation, but it would require students to receive tutoring in fourth grade if they pass the screener test.

J.C. Bowman, executive director and CEO of Professional Educators of Tennessee, called the proposed amendment a “positive step” because it bases retention on more than a single test score. But with such a short timeline, he said districts need to ensure parents understand all the options.

Seeking ‘adequate growth’

State lawmakers approved the 2021 legislation — officially called the Tennessee Learning Loss Remediation and Student Acceleration Act — alongside a complementary law that overhauls how the state teaches students to read. Districts must now use a phonics-based curriculum, and the state has spent the last two summers training teachers in the so-called “science of reading.”

But Sonya Thomas, executive director of Nashville Propel, a parent advocacy group, questioned why schools didn’t have children repeat kindergarten instead of waiting until third grade.

“At that point, school districts knew who was behind,” she said, “What have they been doing since then?”

As the law currently stands, students who score in the “approaching” range — and don’t reach proficiency when they retake the test — can attend summer school or participate in tutoring in fourth grade. In summer school, they must have 90% attendance and make progress in reading.

Those who score “below expectations” have to participate in both tutoring and summer school. But some question whether six weeks of summer learning camp will be enough to prepare students for the demands of fourth grade.

“It’s not just like we’re going to eat popsicles and play outside,” said Jean Hesson, elementary supervisor for the Sumner County Schools. But she said it’s also unrealistic to expect a student who is two years behind to reach grade level just because of summer school. “We would love to see adequate growth.”

Director Satterfield said even if families take advantage of all the opportunities for extra help, their children might still be too far behind.

“Are we really going to fail those students?” he asked the committee.

Retention research

Lawmakers in other states have been asking similar questions. Retention opponents in Ohio, including the Ohio Education Association, unsuccessfully pushed for a repeal of that state’s law last fall. In Michigan, however, both the House and Senate have passed a bill that ends third grade retention Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is expected to sign.

When the Michigan law went into effect last school year, only 1% of students eligible for retention were ultimately held back, according to data from Katharine Strunk, a Michigan State University professor tracking the law’s implementation. She argues that the costs of making students repeat a grade outweigh the benefits and that retention predominantly affects low-income and minority students.

But former Mississippi state chief Carey Wright and former literacy director Kymyona Burk told Tennessee lawmakers that retention was one important trigger that led to what some have called a “miracle.” In 2019, Mississippi was the only state to show gains in fourth grade reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

They highlighted a recent Boston University working paper showing students who repeated third grade in 2014-15 had higher English language arts scores in sixth grade. ExcelinEd, an advocacy organization where Burk is now senior policy fellow for early literacy, commissioned the report.

“Retention will have a far greater positive impact than moving along a student who just isn’t ready,” they wrote in a recent op-ed for The 74 about the research.

Another recent analysis found that Indiana fourth graders who repeated third grade scored higher on state math and reading tests than third graders who barely passed. Retained students continued to outperform those who weren’t retained through seventh grade and were not more likely to have problems with absenteeism or behavior.

Some experts acknowledge that retention can lead to short-term gains, but warn it has serious consequences later.

In a chapter for a recent book on education policy and literacy, Gabriel DellaVecchia, a researcher at the University of Michigan, reviewed evidence from a 2018 study linking retention in Texas to higher high school dropout rates — especially among Black and Hispanic girls.

“If their grades go up in sixth grade, but they hate school so much that they drop out the moment they turn 16, it is difficult to label the policy as a success,” he told The 74.

He added that when states like Tennessee provide tutoring and summer school, in addition to improving reading instruction, it’s hard to isolate the benefits of retention itself.

“Those same supports could just as easily be provided to a fourth grader,” he said, “without removing the child from their peer group or stamping them with the stigma of being retained.”

Even those with students not yet in third grade have been following the debate.

“It’s like the biggest talk in the city,” said Teaira King of Nashville, whose daughter, 6-year-old Journi Wilson, attends Purpose Preparatory Academy, a charter school.

Based on her own experience, King agreed that schools shouldn’t promote students if they can’t read. But she’s not in favor of retaining students if all they get is a repeat of previous instruction.

She didn’t realize she was a struggling reader until she got to college. She eventually dropped out.

“I don’t want my kids to feel the way I felt when I graduated and I couldn’t read,” she said. “I wasn’t ready for the world.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)